Category: Uncategorized

Moose Skowron: The Merry All-Time World Series Great

The list of the top ten Home Run hitters in World Series history is fascinating, but not for the reasons you’d think.

Mickey Mantle still leads (and almost certainly will; Albert Pujols trails him by 14, cluster-hitter Nellie Cruz trails him by 15, and Alex Rodriguez trails him by 17). Babe Ruth (15) and Yogi Berra (12) follow. Duke Snider is fourth with 11, Lou Gehrig and Reggie Jackson tied for fifth at 10. The rest of the top ten are three men tied with eight homers each: Joe DiMaggio, Frank Robinson, and Moose Skowron.

Moose Skowron?

Bill “Moose” Skowron died today after a fight with cancer. He was 81. He was one of the most appreciated, most fun, most filter-free guys in baseball history (“Keith Olbermann! You look great! But, Jeez, ya put on a little weight, huh?”). For the last 40 years he had gradually become the stuff of anecdotal legend, roaming the various parks of the White Sox and dropping into almost anybody’s broadcast booth and inevitably being asked about the stash of Mantle-signed baseballs he supposedly kept locked away somewhere (“Oh, now don’t start on me about that again, Sheesh, I’m not talkin’ about that again”).

What got lost in all this merriment – and that’s the word for it, Bill Skowron was almost unstoppably merry – was that he was a helluva first baseman, mostly for the New York Yankees. And unless somebody gets on the stick, he is going to be in the top ten in all-time World Series home runs for quite awhile. Because while you may or may not be able to prove that there is such a thing as clutch hitting, Moose Skowron played in 39 World Series games, got 39 hits, hit his eight homers, and drove in 29 runs. He slugged .519, hit two homers in the same Series in two different years, and in the dramatic 7th Game in 1958, with the Yankees having just broken a 2-2 tie in the 8th Inning, he hit a two-out three-run job to kill off the Braves and Lew Burdette (who had only won the Series from the year before by pitching three victories for Milwaukee).

To throw more numbers at you:

Most Career World Series RBI

1. Mickey Mantle 40

2. Yogi Berra 39

3. Lou Gehrig 35

4. Babe Ruth 33

5. Joe DiMaggio 30

6. Bill Skowron 29

Something else to consider about this cascade of stats. Moose would be the first person to tell you he was no Mickey Mantle and certainly no Babe Ruth. But he put up World Series numbers that approach both of them, with far fewer opportunities. In his first three Series, Skowron was platooned by Casey Stengel. He only batted four times in the ’57 Classic.

Skowron only had 142 World Series plate appearances. Mantle had 273, Berra 295, DiMaggio 220. Mantle homered once every 15.2 ups, Skowron once every 17.75, Berra once every 24.6, DiMaggio once every 27.5.

The RBI rate is even more impressive. Rewrite that list based on plate appearances (lower is better), with the caveat that a tack-on Grand Slam, like the Moose hit in Game 7 in 1956, can go a long way.

Plate Appearances Per World Series RBI:

1. Gehrig 4.0

2. Skowron 4.9

3. Ruth 5.0

4. Mantle 6.8

5. DiMaggio 7.3

6. Berra 7.6

Again, Bill’s explanation for this was pretty easy (“I was real lucky”). In point of fact, he produced in this way even though, almost invariably, Mantle, Berra, and later Maris, were batting ahead of him. As often as he might have added tack-on runs, he was probably much more often coming up after one of the epic sluggers had cleaned off the bases. He hit when it counted.

But ultimately, Moose (and although he went to Purdue on a football scholarship he was 5’11” 195 – the “Moose” came from a haircut that made the childhood Bill look like the Italian dictator Mussolini) was just endless good fun. I had the great luck to be invited by Tony Kubek to join his family at the 2009 Hall of Fame inductions. Kubek’s first roomate was Skowron, and they were proud enough of their Polish heritage that Skowron introduced the rookie Kubek to a fellow countryman, Stan Musial to get some batting tips. Moose was sitting next to be as Kubek got up to begin his acceptance of his entry into the Broadcasters’ wing. Kubek smiled towards us and said “I have to start with a story about my first year in the majors, and my first roomie, Moose Skowron, and when he introduced me to Stan Musial.”

Moose buried his head in his hands. “Oh, Jeez, Tony, don’t tell that story,” he muttered, “Jeez, don’t tell that story!” As the MLB Network cameraman raced towards us to get a reaction shot, Bill muttered again, “Keith, can’t you do something to stop this? You’re on tv, ain’t ya?” When I pointed out that I was part Polish, too, Bill sat upright and said “You’re one of us? Well, I guess that means you can’t. I’ll just have to sit here and take this.”

Humber Humbled

The first man Philip Humber faced in the start after his Perfect Game? He walked him. The third? He surrendered a base hit to him. The fourth? He watched him smack an RBI double. In short, after retiring 27 consecutive batters against Seattle, in his next appearance against Boston, before he could get two outs in total, he had lost his shot at a Perfect Game, a no-hitter, and a shutout.

By the third inning, Humber no longer had a homer-free streak, or even a grand slam-free streak. By the fifth, he had gone no games without surrendering two homers to the same guy (Jarrod Saltalamacchia) The Coach had turned back into The Pumpkin.

The vagaries of the perfecto – the idea that a muse appears, gives a pitcher flawless results for three hours or less, then vanishes, never to return – are countless. For virtually every one of the 21 flawless games, I think there are overwhelming mitigating circumstances that made the outcome slightly more possible than usual on the day in question. This would require a lot of research on some of the early games (like the first of the three by the White Sox, by Charlie Robertson in 1922), but just anecdotally: Mike Witt’s 1984 job was on the ultimate getaway day, the season finale between two teams not in the pennant race. When the kinescope of the Don Larsen game resurfaced three winters ago we learned that the batter’s eye at Yankee Stadium had been removed to accommodate the World Series crowd (it is thus more amazing that the Yankees got any hits that day, more than that the Dodgers didn’t). Mark Buehrle’s had an obvious aberration (an epic outfield catch by Dewayne Wise) and a less obvious one (a free-swinging Tampa Bay line-up, in a really early start for a day game after a night game, on getaway day). And as if he needed the help, when Sandy Koufax mesmerized the Cubs in 1965, he was facing a line-up with three future Hall-of-Famers in Ernie Banks, Ron Santo, and Billy Williams. The other six batters were a pitcher, and five rookies – and two of them were playing in their first major league games.

What were the telling signs for Humber? He took no-hit bids into the sixth and seventh last year, had a new pitch that not everybody had seen before (six of the nine Mariner hitters were not in the line-up during his last start against Seattle, even though that was only last June), and is pitching during a time in which the hitters are deflating. Clearly PED use by hitters is down, perhaps by some extraordinary percentage, and lord knows how much that’s reduced strength of contact, let alone results, or even hand-to-eye coordination.

Perhaps the only Perfect Game that gets a note if not an asterisk might be the effort by the great Addie Joss in 1908. As his Cleveland Naps took the field against the White Sox on October 2, 1908, they were half a game behind first-place Detroit, and just a game ahead of Chicago. His future fellow Hall-of-Famer Ed Walsh (who only won 40 games that year) was the opponent. Joss, in the tightest imaginable pennant race, retired all 27 men he faced, and won 1-0, on an unearned run in the third. The degree of difficulty on that was pretty big.

But anyway. In June, 2010, at the end of the Buehrle-Braden-Halladay-Shoulda-Been-Galarraga-Too swarm, I asked here if the achievement itself might have a long-term negative impact on the pitchers involved. It’s time to update that data:

Is there something about getting 27 outs in a row that psychologically alters a pitcher? The sudden realization that you can do it? The gnawing sensation that a “quality start” or even a six-hit shutout just isn’t the ceiling? Or is it possible that a Perfecto really is some sort of apogee of pitching skills, and not merely the collision of quality and fortune? Whatever the impact of the Perfect Game on the Perfect Game Pitcher, six of the other 20 to throw them have not managed to thereafter win more games than they lost. Another was one game over .500. An eleventh was just three games over. Fully fourteen of the pitchers saw their winning percentages drop from where they had been before their slice of immortality (though obviously the figures on Braden, Buehrle, and Halladay are at this point embryonic) Consider these numbers, ranked in order in change of performance before and after. First the good news: it is perhaps not surprising that of the eight pitchers whose percentages improved afterwards, the two most substantial jumps belong to Hall of Famers.

Jim Hunter Before: 32-38, .457

Jim Hunter After: 191-128, .599

Jim Hunter Improvement: Winning percentages jumps 142 points

Sandy Koufax Before: 133-77, .633

Sandy Koufax After: 31-10, .756

Sandy Koufax Improvement: 123

Koufax is a bit of an aberration, since that 31-10 record, gaudy as it seems, represents only one season plus about a month, before his retirement in November, 1966. Five of the other six improvements are a little more telling.

David Wells Before: 110-86, .561

David Wells After: 128-71, .643

David Wells Improvement: 82

Don Larsen Before: 30-40, .429

Don Larsen After: 51-51, .500

Don Larsen Improvement: 71

Roy Halladay Before: 154-79, .661

Roy Halladay After: 36-14, .720

Roy Halladay Improvement: 59

Mike Witt Before: 37-40, .481

Mike Witt After: 79-76, .510

Mike Witt Improvement: 29

Dennis Martinez Before: 173-140, .553

Dennis Martinez After: 71-53, .573

Dennis Martinez Improvement: 20

There is one improvement that is really misleading. Dallas Braden hadn’t been much of a pitcher before his 2010 perfecto. Since, he’s been ok – he just hasn’t pitched much:

Dallas Braden Before: 17-23, .425

Dallas Braden After: 8-7, .533

Dallas Braden Improvement: 108

For everybody else, the Perfect Game has meant comparative disaster. We can again discern some unrelated factors: many pitchers threw their masterpieces late in their careers (Cone), late in life (Joss died about 30 months after he threw his), or not long before injuries (Robertson and Ward, the latter of whom would switch positions and become a Hall of Fame shortstop). Still, the numbers don’t augur well for our trio of active guys. They are listed in here in terms of the greatest mathematical drop from career Winning Percentage before the game, to career Winning Percentage afterwards:

David Cone Before: 177-97, .646

David Cone After: 16-29, .356

David Cone Dropoff: 290

Lee Richmond Before: 14-7, .667

Lee Richmond After: 61-93, .396

Lee Richmond Dropoff: 271

Jim Bunning Before: 143-89, .616

Jim Bunning After: 80-95, .457

Jim Bunning Dropoff: 159

Len Barker Before: 33-25, .569

Len Barker After: 40-51, .440

Len Barker Dropoff: 129

Charlie Robertson Before: 1-1 .500

Charlie Robertson After: 47-79, .373

Charlie Robertson Dropoff: 127

Mark Buehrle Before: 132-90, .595

Mark Buehrle After: 29-32, .475

Mark Buehrle Dropoff: 125

Addie Joss Before: 140-79, .639

Addie Joss After: 19-18, .514

Addie Joss Dropoff: 125

Cy Young Before: 382-216, .639

Cy Young After: 128-116, .525

Cy Young Dropoff: 114

Randy Johnson Before: 233-118, .664

Randy Johnson After: 69-48, .590

Randy Johnson Dropoff: 74

Johnny Ward Before: 80-43, .650

Johnny Ward After: 81-60, .574

Johnny Ward Dropoff: 46

Tom Browning Before: 60-40, .600

Tom Browning After: 62-50, .554

Tom Browning Dropoff: 46

Kenny Rogers Before: 52-36, .591

Kenny Rogers After: 166-120, .580

Kenny Rogers Dropoff: 9

If you’re wondering: Phil Humber was 11-10 before he performed his magic against the Mariners.

So Could They Actually Fire Bobby V?

On May 23, 1993, the Cincinnati Reds stunned the baseball world. Just 44 games into a season in which they were only four below .500, they fired first-year manager Tony Perez and replaced him with Davey Johnson.

I’m not claiming this is the definitive record for the fastest blowout of a new skipper but those of us sitting around the press box at CitiField tonight think it is. We knew the Reds’ Hall of Famer went out even faster than had poor Les Moss, finally given a shot to manage in the majors after 20 years’ apprenticeship as a coach, only to be cashiered by the Tigers in favor of Sparky Anderson on June 11, 1979.

Is it possible? Would anybody – let alone the Red Sox – off a high-profile skipper 40 games into his tenure? Or 30? The question certainly seems increasingly less like science fiction with every passing day. Now we hear Valentine won’t put Daniel Bard back in the bullpen because he doesn’t want to go.

Man alive, if that’s the real reason, there’s no need to fire poor Bobby. If third-year ex-set-up men get to dictate their roles on a pitching staff we can expect Valentine to just slowly vanish like the Cheshire Cat.

The Red Sox have done some goofy managerial things, and in recent memory. In mid-August 2001, in second place and just five games out, they fired manager Jimy Williams and made pitching coach Joe Kerrigan the skipper. The Sox proceeded to go 17-26 and end up 13-and-a-half out. As the new ownership group took over, they fired Kerrigan and put in coach Mike Cubbage as a spring training caretaker. When the John Henry gang was given formal control of the franchise, Cubbage was fired without ever managing a regular season game. Were that not bizarre enough, this was all done so they could make the ill-fated Grady Little the skipper.

By the way just to clarify – Perez is not the manager fired fastest. We’re limiting this to guys in Valentine’s shoes: newly hired to start a season (and in the cases of Moss and Perez, quickly fired). The overall fastest record either belongs to Cubbage or Wally Backman, hired and fired in the same off-season by the Diamondbacks. Or if you’d prefer the quickest in-season exit, that has to be Eddie Stanky. Lured back to the majors after eight years coaching in college, Stanky took the reins of the Rangers on June 22, 1977. Stanky’s new team beat the Twins 10-8, whereupon Stanky told the startled media that he’d made a huge mistake – and was resigning.

Now Appearing In Your Picture

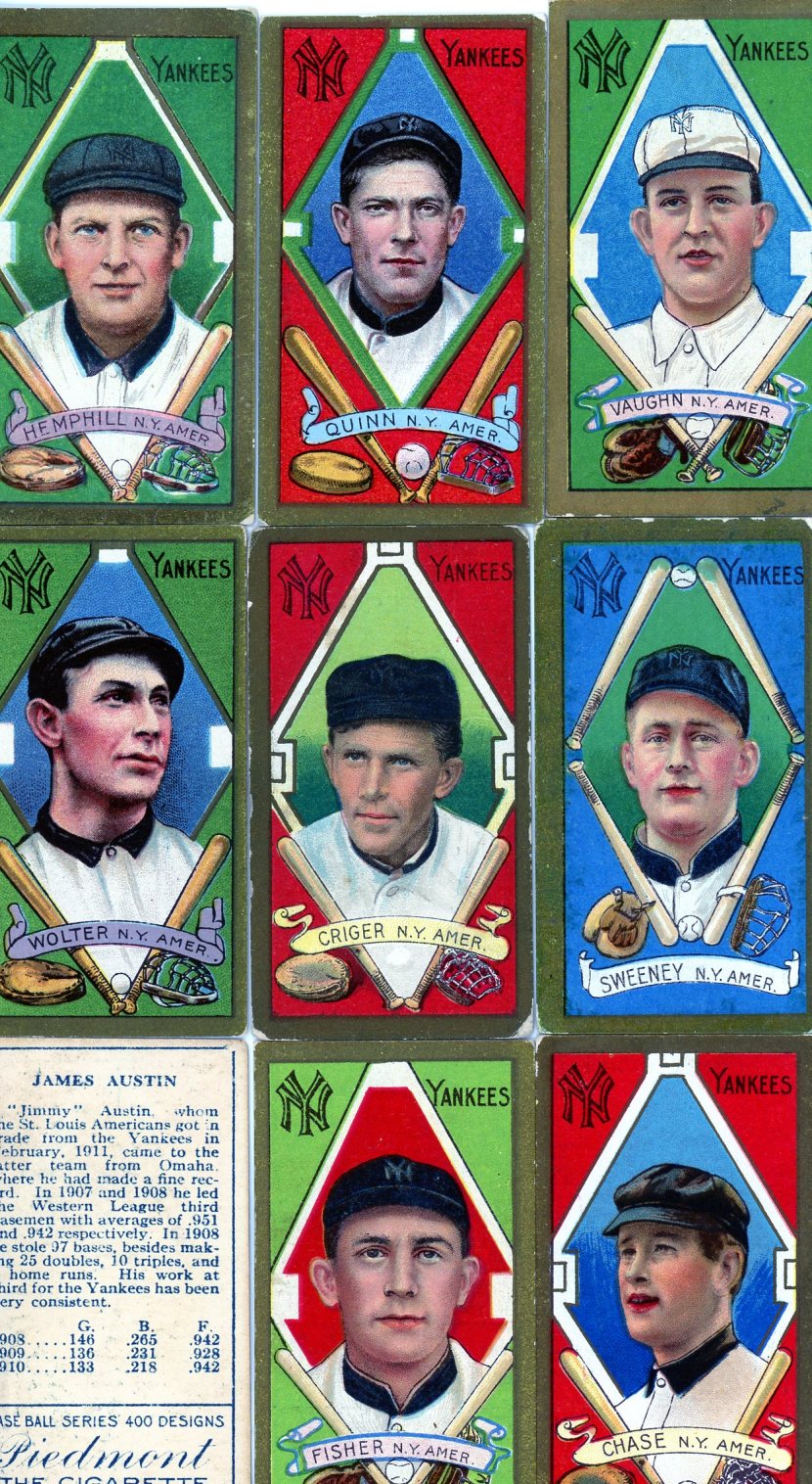

All this time this weekend debating when the “Highlanders” nickname was phased out, and the “Yankees” nickname phased in, and I missed a jewel sparkling up from one of my primary pieces of evidence.

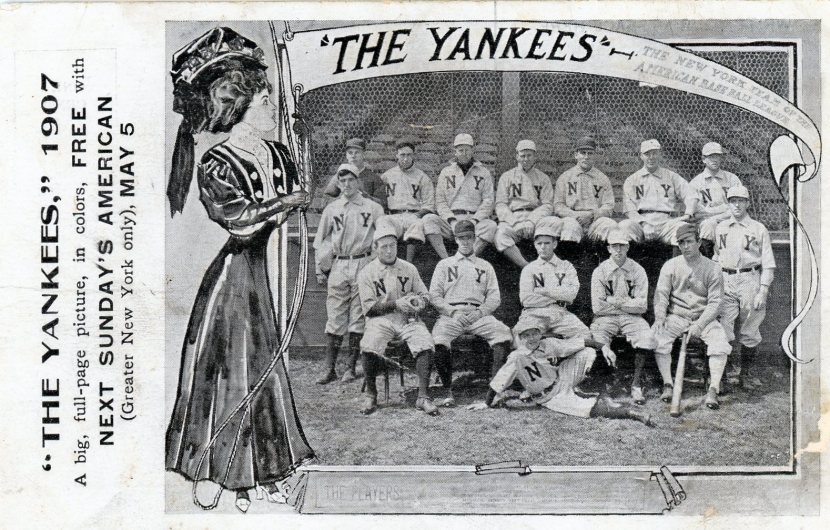

Take a good look at the stern faces in this photo, particularly in the back row, sitting on the fence at old Hilltop Park: The Yankees – and if the editors of the New York American of 1907 decided to try to sell newspapers by giving away these postcards, and a special supplement of this photo, by calling them the Yankees, so will I – had traded veteran Joe Yeager to St. Louis a month before spring training for a promising but ultimately disastrous utilityman.

The Yankees – and if the editors of the New York American of 1907 decided to try to sell newspapers by giving away these postcards, and a special supplement of this photo, by calling them the Yankees, so will I – had traded veteran Joe Yeager to St. Louis a month before spring training for a promising but ultimately disastrous utilityman.

He was listed as a catcher, but on June 28th with him behind the plate, the Washington Senators stole 13 bases against the Yankees. Thirteen. “My arm was numb and I was helpless to do anything.

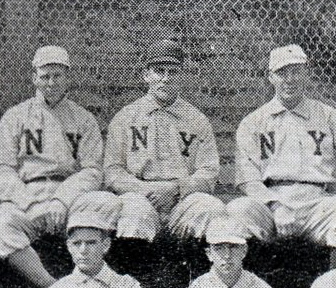

Take a closer look at him, in the black cap. Do the eyebrows look familiar? That’s Branch Rickey.

That’s Branch Rickey.

The Branch Rickey. 40 years later he’d be ushering Jackie Robinson in the majors.

And parenthetically, front row, on the left in this detail? Another Hall of Famer, 1907 Yankees manager, future Washington Senators owner, Clark Griffith.

End Of Story: The 1912 New York Yankees.

This post contains new material and much reworked from Friday’s.

I thought we had cleared this up yesterday, but evidently not. Now my old friend Joe Buck has repeated a mistake that has unfortunately attained the aura of official history. Simply put, when the Boston Red Sox opened Fenway Park 100 years ago Friday, the faithful would have called the visiting team “The New York Yankees” – not “The New York Highlanders” (we’ll leave out any more troublesome things they might’ve called them).

The April 12, 1912 edition of The New York Times wrote of the club’s home opener: “The Yankees presented a natty appearance in their new uniforms of white with black pin stripes.”

Below you’ll see the 1911 baseball cards issued with the brands of the American Tobacco Trust, labeling the New York players “Yankees,” plus a newspaper supplement from 1907 showing a team picture of the New York Yankees.

My friend Marty Appel is just out with his comprehensive history of the franchise, Pinstripe Empire. He has some succinct insight into the etymology of the New York American League club’s name:

“Today we think the field was commonly called Hilltop Park, and the team commonly called the Highlaners. But in the first decade…the team was also better known as the New York Americans or the Greater New Yorks. On opening day (1903), the Telegram called them the Deveryites. Sam Crane in the Evening Journal was determined that they be the Invaders. In those days, team nicknames were far less formal. It was, for example, more common to say the Bostons or the Boston Americans than to call them the Red Sox or the Pilgrims.

“Hilltoppers was also used on occasion, and as early as April 7, 1904, the Evening Journal used YANKEES BEAT BOSTON in a headline. (“Highlanders” didn’t even appear in the New York Times until March 1906).”

Appel also quotes a piece from the legendary writer and historian Fred Lieb, from Baseball Magazine, in 1922:

“(Highlanders) was awkward to put in newspaper headlines. Finally the sporting editor at one of the New York evening papers exclaimed ‘The hell with this Highlanders; I am going to call this team ‘the Yanks’ that will fit into heads better.’

“Sam Crane, who wrote baseball on the same sheet, began speaking of the team as the Yankees and Yanks. When other sporting editors saw how much easier ‘Yanks’ fit into top lines of a head, they too (decided against) Highlanders, a name which never was popular with fans.”

The further back you go before the rust formed around the official history, the further it becomes clear that until the owners officially christened the team in 1913, they were known informally by many names. “Yankees” seems to have been an early favorite, “Americans” being the default second choice (just as it would’ve been for the Cleveland “Americans” or the Detroit “Americans” or – translated to the other league – for the Philadelphia “Nationals”). “Highlanders,” “Hilltoppers” and “New Yorks” brought up the rear.

It’s also pretty clear that the New York team we know as the Yankees was never formally called “Highlanders.”

I first heard the story of the slow evolution from “Gordon’s Highlanders” (the name of a famed British army regiment of the time, which stuck because the first team president was named Joseph Gordon, and because their ballpark was at one of the highest spots in New York) to the Yanks in Frank Graham’s first version of The New York Yankees in 1943. At that time, a lot of people who had seen the full 40-year history of the franchise were still alive – Graham, who became a sportswriter in 1915, included. I read the copy my father had had since childhood, either in 1967 or 1968.

The relevant passage is on Page 16:

“With 1913 coming up, there was an almost complete new deal. Jim Price, Sports Editor of the New York Press, had been calling the team the Yankees because he found the name Highlanders too long to fit his headlines; and by 1913 the new name had been generally adopted.”

So the Yankees were the last people to call themselves the Yankees and as Graham wrote nearly 70 years ago, the nickname had been generally adopted before the club went through the formality – in 1913.

The key to all this is Appel’s observation that nicknames were informal until the clubs began to realize they were marketing and merchandising opportunities, which probably didn’t take place until the 1920’s. Official MLB history and fans have totally reversed the team name equation. It used to be all about the cities (the 1889 World Series was “The New Yorks versus The Brooklyns”) and this is something that just does not compute to the modern mind. In fact, think of the Dodgers, who began as a new franchise in the then-major league American Association in 1884 with the uninspired nickname “Grays.” By 1888, after a spate of players got married in the off-season, they were the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. In 1899 when Ned Hanlon took over as manager, there was a famous vaudeville troupe called “Hanlon’s Superbas”- thus they became the Brooklyn Superbas. The name outlasted Hanlon, and only faded when Wilbert Robinson took over as manager in 1914 and the name changed again: Brooklyn Robins. Throughout this whole time, the fans and sportswriters used, as a kind of alternative nickname, the term applied to Brooklyn fans who were in constant danger from the labyrinth of streetcar lines throughout the city: “The Trolley Dodgers,” or, simply “Dodgers.” So when Robinson left after the 1931 campaign, the club formally declared themselves “The Dodgers” (but didn’t put the name on the uniforms until 1938). How did the Dodgers treat this confusing history? They declared their 100th anniversary to be 1990, which wiped out the 1884-89 time frame and the team’s first trip to the World Series.

And just think, we can go through this entire history controversy year after next. 2014 will be the 100th Anniversary of Wrigley Field. Only it wasn’t called Wrigley Field in 1914 and the Cubs didn’t play there until 1916.

First, back across the country and the Yankee photographic evidence.

Tip of the cap to my fellow SABR member Mark and this evidence-filled blog on the issue. He gives prominent attention to headlines from the New York Sun about the 1912 “Highlanders.” Getting lesser play? This clip from the New York Tribune, which echoes the aforementioned Times headline: Interestingly the Sun folded in 1950. The Tribune was still breathing (after a series of mergers) in 1966. The Times is still in business.

Interestingly the Sun folded in 1950. The Tribune was still breathing (after a series of mergers) in 1966. The Times is still in business.

Then there’s this from 1907:

That is a postcard advertising the following Sunday’s edition of The New York American newspaper, which was to include a full-sized version of the 1907 Yankees team picture. This was just after 1907’s opening day, five years before the christening in The Fens.

That is a postcard advertising the following Sunday’s edition of The New York American newspaper, which was to include a full-sized version of the 1907 Yankees team picture. This was just after 1907’s opening day, five years before the christening in The Fens.

Below, the 1911 baseball cards. In some of the biographies (as shown in the lower left hand corner) there are references to “Highlanders.” But the fronts tell the story:

By the way, “Quinn” in the top row? That’s Jack Quinn, whose oldest-victory mark was just broken by Jamie Moyer. These are 1911 cards. Quinn is also in the 1933 set.

By the way, “Quinn” in the top row? That’s Jack Quinn, whose oldest-victory mark was just broken by Jamie Moyer. These are 1911 cards. Quinn is also in the 1933 set.

In point of fact, the Yankees were the Yankees before the Red Sox were the Red Sox. Created in 1901 when the American League was founded, the Boston team was known variously as the Pilgrims, and simply “The Americans” (as opposed to “The Nationals”), the new team drew much of its talent from the successful, but eminently cheap National League team in Boston. From its earliest days in the National Association (1871) and N.L. (1876) that team had worn red stockings, and were once formally known by that name.

In 1907, the N.L. team’s manager Fred Tenney became worried about the threat of blood poisoning supposedly posed by the red dye in the socks getting into spike wounds. By year’s end, he had convinced owners John and George Dovey to eliminate the color from the uniforms. A block away, where the nascent A.L. team was struggling to gain a foothold in what was still a National League town, owner John I. Taylor immediately jumped on the opportunity and announced his team would don “the red socks” in 1908 – and a name was born.

The Yankees were the Yankees by 1906. The Red Sox weren’t the Red Sox until 1908.

Parenthetically, the N.L. team’s next nicknames – the Doves, for the Dovey Brothers, and, in 1911, the Rustlers (because Doves increasingly sounded stupid) – didn’t catch on. The Doveys sold out in 1912 to a bunch of New York politicians from Tammany Hall. Since that organization had a Native American for its logo, its operatives were known as “braves” – and thus the Boston N.L. club adopted that name, and have carried it since. In fact, a week ago Wednesday was the 100th Anniversary of the first appearance of the Braves.

Update: Wonderful Ceremony, But They Weren’t The Highlanders

Kudos to the Red Sox for taking the concept of the mega-ceremony to a new level. Whereas the Yankees closed the old Stadium in 2008 by putting a comparatively small group of all-time greats on the field at their old positions, the Olde Towne Team went the egalitarian route, and for once, bigger really was better.

The ovation for Terry Francona was terrific, and the scene of Tim Wakefield and Jason Varitek pushing the wheelchairs of the long-ago doubleplay combo of Bobby Doerr and Johnny Pesky was indelible. But to me, just as important was seeing Bobby Sprowl and Billy Rohr and Wayne Housie and Jim Landis and those other dozens of the 230 in attendance whose Red Sox tenures were more cameos than careers.

This is the essence of the difference between the franchises. The Yankees are about an elite, and a sense that only the best even matter. The Red Sox – at least until ownership went crazy last fall and cut off its nose to spite its face – have always been predicated on the idea that everybody, great or trivial, has contributed something to the heritage.

I will protest, however, on behalf of historical accuracy, the continual references right now to how the opponents in both today’s game and the first ever at Fenway exactly a century ago were the New York “Highlanders.” This is one of those misunderstandings of history that never seems to get straightened out. Yes, the New York American League team was colloquially known as “The Highlanders” when it was moved from Baltimore in 1903. And yes, the name “Yankees” wasn’t formally adopted until 1913.

That does not mean the 1912 New York team wasn’t known as the Yankees. In fact the name was in common use no later than 1907. Evidence? That is a postcard advertising the following Sunday’s edition of The New York American newspaper, which was to include a full-sized version of the 1907 Yankees team picture. This was just after 1907’s opening day, five years before the christening in The Fens.

That is a postcard advertising the following Sunday’s edition of The New York American newspaper, which was to include a full-sized version of the 1907 Yankees team picture. This was just after 1907’s opening day, five years before the christening in The Fens.

They were the Yankees. Not the Highlanders. Stop saying it.

Update: Yes, I understand that the Yankees’ official history identifies the pre-1913 teams as the Highlanders and doesn’t assign the “Yankee” name to the teams until after the 1912 season. But this isn’t about a simplified record for people who don’t really care about historical accuracy (another example: the Dodgers claim their franchise began in 1890, when in fact the 1890 team was the same one that represented the old American Association in the 1889 World Series). This is about what the fans at brand new Fenway Park, a hundred years ago today, would’ve called the visiting team from New York.

Second Update: As those who never question “history” continued to push back on this idea that because the team didn’t officially call itself the Yankees until 1913 it wasn’t the Yankees in 1912, I decided to go back to where I first heard the story of the slow evolution from “Gordon’s Highlanders” (the name of a famed British army regiment of the time, which stuck because the first team president was named Joseph Gordon, and because their ballpark was at one of the highest spots in New York) to the Yanks. Frank Graham wrote his first version of The New York Yankees in 1943, when a lot of people who had seen the full 40-year history of the franchise were still alive – Graham, who became a sportswriter in 1915, included. I read the copy my father had had since childhood, either in 1967 or 1968.

The relevant passage is on Page 16:

“With 1913 coming up, there was an almost complete new deal. Jim Price, Sports Editor of the New York Press, had been calling the team the Yankees because he found the name Highlanders too long to fit his headlines; and by 1913 the new name had been generally adopted.”

So the Yankees were the last people to call themselves the Yankees and as Graham wrote nearly 70 years ago, the nickname had been generally adopted before the club went through the formality – in 1913.

Some of the less in-the-know fans at Fenway at its christening might have referred to the visitors as “The Highlanders.” The vast majority would’ve said “Yankees” – as the New York Times had after the 1912 opener in New York: “The Yankees presented a natty appearance in their new uniforms of white with black pin stripes.”

More evidence? In the biographies on the back (as shown in the lower left hand corner), there are occasional references to “Highlanders.” But the 1911 baseball cards refer to them – unofficial or not – as the Yankees: By the way, “Quinn” in the top row? That’s Jack Quinn, whose oldest-victory mark was just broken by Jamie Moyer. These are 1911 cards. Quinn is also in the 1933 set.

By the way, “Quinn” in the top row? That’s Jack Quinn, whose oldest-victory mark was just broken by Jamie Moyer. These are 1911 cards. Quinn is also in the 1933 set.

In point of fact, the Yankees were the Yankees before the Red Sox were the Red Sox. Created in 1901 when the American League was founded, the Boston team was known variously as the Pilgrims, and simply “The Americans” (as opposed to “The Nationals”), the new team drew much of its talent from the successful, but eminently cheap National League team in Boston. From its earliest days in the National Association (1871) and N.L. (1876) that team had worn red stockings, and were once formally known by that name.

In 1907, the N.L. team’s manager Fred Tenney became worried about the threat of blood poisoning supposedly posed by the red dye in the socks getting into spike wounds. By year’s end, he had convinced owners John and George Dovey to eliminate the color from the uniforms. A block away, where the nascent A.L. team was struggling to gain a foothold in what was still a National League town, owner John I. Taylor immediately jumped on the opportunity and announced his team would don “the red socks” in 1908 – and a name was born.

The Yankees were the Yankees by 1906. The Red Sox weren’t the Red Sox until 1908.

Parenthetically, the N.L. team’s next nicknames – the Doves, for the Dovey Brothers, and, in 1911, the Rustlers (because Doves increasingly sounded stupid) – didn’t catch on. The Doveys sold out in 1912 to a bunch of New York politicians from Tammany Hall. Since that organization had a Native American for its logo, its operatives were known as “braves” – and thus the Boston N.L. club adopted that name, and have carried it since. In fact, a week ago Wednesday was the 100th Anniversary of the first appearance of the Braves.

2012 Previews: N.L. West

Yes, I know.

This is the latest “preview” of a baseball divisional race ever written. It is penned with the full knowledge of the Dodgers’ 10-3 start, and the injury swarm that seems to be forming in the Arizona outfield, and the demise of Brian Wilson. My apologies: I got kinda behind thanks to Ozzie Guillen and Fidel Castro and stuff.

–

I’ve known Don Mattingly for just under 30 years now. To try to define the eternal nature of Opening Day in a piece for CNN in 1983 I interviewed the oldest old-timer on the Yankees, my late friend Bobby Murcer, and the youngest kid on the squad, a guy who was still wearing uniform number 46 named Mattingly. He didn’t say much, but somewhere there is still a tape of him as the interview closed, thanking me (for some reason). Several seasons, one batting championship, an MVP, and about five Gold Gloves later, I remember going in to the Yankee clubhouse before a game to ask him one question, only to find him answering a question about selecting bats from a fellow fromSports Illustrated. Then there was a second question. And a third. And a tenth. And a twentieth. And Mattingly answered them all. A lifetime later, in his first trip back to New York as a manager, I watched him do every interview, sign every autograph, and smile at everybody who said hello.

Finally I asked him how, and why, he did it. “Why not? Doesn’t cost me much. I smile, or I do an impression of a smile, or I’m interested, or I try to be interested, and when I need something from that person, they usually do their best.” I thought that was deeply revealing, and although it might read a little cynical, I didn’t feel that it was. Don Mattingly is genuinely patient with everybody. But when the patience – as it inevitably must – runs out, he manages to simulate it a little longer than the rest of us.

This might define the greatest skill a baseball manager can have.

This might also define why, in his second season, Mattingly is beginning to be viewed as one of the game’s up-and-coming managerial stars. With no managerial experience at all, he willed a pretty limp ballclub with the worst ownership in the sport in at least a decade, which had four different closers, and exactly one guy with more than 65 RBI, to three games above .500 and the seventh best record in the league.

This does not mean he is going to put them in the playoffs this year. Simply put, the Dodgers are not going to get 224 RBI each from Andre Ethier and Matt Kemp, nor 75 saves from Javy Guerra. They are going to be hard-pressed to compete if they don’t correct the disproportions of the offense through the first thirteen games:

PLAYERS HR RBI

Ethier & Kemp 11 36

Everybody Else 1 24

“Everybody else” in LOS ANGELES seems to be named Ellis. They aren’t, of course. But they do have something in common. With the exception of Jose Uribe, they’re all pretty good defensive players, and as he’s shown early, his sub Jerry Hairston can often be a defensive revelation, at least in short bursts. The Dodgers also have a deep bullpen with a lot more depth available in Albuquerque. I am suspicious of the starting beyond Kershaw and perhaps Billingsley. Still, if the starters come through and the inevitable fits-and-starts of young Dee Gordon prove a net-plus, the Dodgers could compete in what is evidently going to be a depleted division.

ARIZONA looks like it will be struggling along with a makeshift outfield. This may not be a fatal thing; the team loves A.J. Pollock, and Gerardo Parra is at minimum an asset on defense. But I think the Diamondbacks and those picking them to succeed again in this division are really guilty of making assumptions about the pitching. Daniel Hudson and Ian Kennedy were both likely to correct downwards under the best of circumstances, Josh Collmenter’s success was illusory, Joe Saunders is a journeyman, Trevor Cahill an uncertainty, and Trevor Bauer a rookie who likes to run up on to the mound and throw a warm-up pitch all in one motion and I keep thinking of the late Eddie Feigner, the softball legend from The King And His Court. The dominant bullpen of 2011 is – even if it repeats its success – made up of spare parts (and a lot of them, spare parts the Oakland A’s traded for reasons other than money, which scares me). The Diamondbacks’ best bet might turn out to be a largely rebuilt rotation, made up of Bauer and Wade Miley and maybe even Tyler Skaggs, because I think starting pitching is going to decide the division.

That is what SAN FRANCISCO has. No offense, a lot weaker bullpen than everybody thinks (and that was before Wilson’s injury), and the sport’s second-worst management of young players next to the annual abuse drama in Cincinnati. But of course nobody since the 1971 Orioles has had exactly enough starting pitching, and even their four 20-game winners somehow contrived to lose the World Series. Here are Cain and Bumgarner under contract forever, and a revivified Barry Zito, and a Ryan Vogelsong who is surprising even the Giants with unexpected health – and yet there is Lincecum pitching as if that painful-looking delivery of his has become a painful-feeling delivery. With Eric Surkamp ailing and Jonathan Sanchez traded there is very little depth should something prove genuinely wrong with the Little Lord Fauntleroy of the Pitcher’s Mound.

And speak to me not of Santiago Casilla and Bullpen By Committee – the problem with the Committee isn’t the need to rely on multiple closers but the way that need deranges the roles of the set-up guys, and without the set-up guys fitting tightly into well-grooved slots, the 2010 World Champs don’t even make the playoffs. This team might fall away quickly, which would at least allow them to audition Heath Hembree as Wilson’s successor (unless Bruce Bochy decides it would be fun to give Guillermo Mota or maybe Al Holland a 47th shot).

There is something wrong in COLORADO and it is being obscured by the ultimate feelgood story for rapidly aging fans and writers alike (“Guy Who Cubs Wanted To Make A Minor League Coach 29 Years Ago Wins Big League Game”). It’s lovely to see Jamie Moyer still successful when his exact contemporary Bo Jackson already has an artificial hip and is throwing out the ceremonial first pitch, but it does remind me of Phil Niekro’s relative success in his career codas in New York and Cleveland: What is this, baseball during World War II? All the non 4-F’s are on the richer teams? Where are the Moscosos and the Chatwoods and the Pomeranzes and the Whites and why did you trade for them if you weren’t going to use them? And by the way, why are you auditioning a 37-year old first-time closer? And how come there is no actual third baseman, nor even one in AAA to fill in until Nolan Arenado is ready?

This means SAN DIEGO might sneak out of last place. Cory Luebke is on the verge of greatness and Chase Headley might be joining him. If Carlos Quentin comes back early enough to make any kind of contribution the Padres will have a better day-to-day line-up than the Rockies. Their rotations and bullpen already seem about even (though I’m not sure who takes over for Huston Street when they deal him at the deadline).

THE 2012 NL WEST FORECAST:

OK. You give me a 10-3 start and the injuries in Arizona and San Francisco and I’ll take the still-long odds against the Dodgers, with the Diamondbacks second, Giants third, Padres edging the Rockies for fourth. The problem, even with two weeks of baseball clarifying the view in the crystal ball, is that all five of these teams have paper-thin depth and another injury (Ethier again? Maybe Tulowitzki’s six early errors are hinting at one?) could topple all forecasts.

THE 2012 OVERALL FORECAST:

Again, kind of late. But I do not abandon my forecasts even when the early season suggests they’re bad ones (I’m looking at you, Phillies). In the NL I’ve already picked the Phils, Cardinals and now Dodgers. The east will produce both Wild Cards, probably the Braves and Nationals, and I guess I like the former (though now we see just how much a built-in one-game playoff will blunt not just the last-day excitement, but also predictions – you’re supposed to pick two wild cards and then choose which will win their single-game decider?). Let’s assume the Wild Card winner knocks off the best record (probably St. Louis) and the Phils’ experience propels them past L.A. That means a Braves-Phillies NLCS and I can’t see anybody beating the Phils’ front three.

The American League is a little easier. Tampa, Detroit, and Texas win the divisions. The Angels and Jays are the Wild Card and the Angels are likelier to win that. Detroit has the weakest division and thus the best shot at the best record, but sadly all that pitching and all that offense only prevails over intervals of ten games or more when the defense is as bad as it is. Thus the Wild Card Angels over Detroit, Tampa (finally) over Texas, and the Rays over the not-quite-good-enough Cherubs in the ALCS.

This leaves me with the same Rays-Phillies World Series I wrongly picked last year, which proves that even making your seasonal predictions 15 days into the season may not be any advantage at all.

Jackie Robinson: Nothing Inevitable About Him

One of the few infuriating aspects of Jackie Robinson Day is the blowback from the uninformed. I have read today of how integration in this country was inevitable, and Robinson’s success in 1947 was just a happy coincidence. I have read that the talent of the Negro Leagues was just too great and had Robinson failed, had he hit .197 instead of .297, it was still inevitable that those great athletes would have forced their way into the mainstream of American sports.

Utter nonsense.

Was it inevitable when Frank Grant led the International League in homers in 1887? Was it inevitable when John McGraw put the great second baseman Charlie Grant on his 1901 Baltimore Orioles squad under the pretense that he was a Native American named Tokohama? Was it inevitable when the Oakland Oaks of the PCL signed pitcher Jimmy Claxton in 1916 only to drop him days later? Was it inevitable when Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson both played in Pittsburgh in the early ’30s and the Pirates desperately needed a starting pitcher and a catcher? Was it inevitable when John Henry Lloyd and Cool Papa Bell and Judy Johnson and Jose Mendez and nearly three dozen more future Hall of Famers spent their entire lives playing for peanuts in separate and unequal conditions?

Baseball had fought integration ever since the 1884 major league team in Toledo signed Fleet and Welday Walker. It had slowly closed the door on African-American players in the minors, through boycotts and threats, and by 1900 they were all gone. And the spasmodic attempts to sneak in a Grant or a Claxton as a Native American had been met with crushing responses and threats of retribution. Even when Robinson seemed safely over the threshold, other teams integrated haltingly and – as in St. Louis with the Browns – sometimes disastrously. Many of the others hung back. The New York Yankees saw nothing “inevitable” about integration: they did not add a black player until Elston Howard in 1955.

While the Boston Braves were signing Hank Aaron and Billy Bruton and Wes Covington and then moving to Milwaukee to win pennants with them, the Boston Red Sox chose not to sign Robinson in 1945, and not to add any African-American player until 1959. The Sox, intentionally or otherwise, kept to a limit of no more than five African-American players on their roster well into the ’70s. It was maintained with extraordinary efficiency. On June 14, 1966, the Sox made a trade that added the former Negro Leagues pitcher John Wyatt to their bullpen. On June 15, 1966, they gave away pitcher Earl Wilson to the Detroit Tigers and their quota was back down to five.

And there was nothing inevitable about black athletes getting another chance in the major leagues had Jackie Robinson failed. He didn’t win the civil rights war by himself (indeed, it has hardly been won), but his role was pivotal and unique. Leaders from each decade and every perspective have said that Robinson provided the cultural groundwork that made integration not necessarily possible, but practical. Unlike Jack Johnson or the less threatening Joe Louis, he had succeeded in a previously all-white team sport. He had white teammates and white friends.

It is little credited today, but Jackie Robinson’s real contribution was not to convert the haters and the proactive racists towards an enlightened view of this country. In fact, what he did would’ve been impossible before the vastly increased interaction between whites and blacks in the military during World War II, and it might’ve been impossible if he had then failed on the ballfield or in his relationship with his white teammates: He erased benign prejudice.

My late father, nearly as liberal a man as I’ve ever known, used to look back at attending games of the New York Black Yankees as a teenager, with a sense of astonishment and shame. “It never occurred to us, never occurred to us, that the black players didn’t want to play only with other black players. We had no idea this was segregation. We thought it was choice.”

And for every open-minded individual like him whose consciousness was raised by Jackie Robinson, there was another who had no animus towards blacks but was convinced that there was either no way they had the athletic chops to succeed at the major league level, or no way they had the psychological stability to withstand the pressure of the game or of the process of integration.

Some large, but ultimately never-to-be-measured, group of Americans went from believing in 1946 that blacks had chosen their own world, or couldn’t physically or psychologically function next to whites, to realizing that these convictions were the most insidious forms of racism. These were the white men and women who supported Brown v. Board of Education, and the marches in the South, and the integration in Little Rock, and Martin Luther King, and the repeal of the laws forbidding blacks to marry whites that stayed on the books of some states as late as the mid-’60s. These were the men and women who began to attend pro football and basketball games in the large numbers they needed to succeed as stable national enterprises only after these leagues began to fully integrate – and, yes, the NBA didn’t integrate until Robinson had completed his fourth season with the Dodgers.

It is imperative to remember that none of the progress – in baseball or in America – that followed in Jackie Robinson’s wake was inevitable. There were millions of hateful Americans who would have exploited a Robinson failure to roll back the limited gains of the war years. There were millions more who would’ve thought that Robinson’s season, or half-season, or six weeks in the spotlight, had been a noble experiment, but that he and his race just weren’t up to it. And when their support was needed to beat back the Orval Faubuses and Bull Connors and Strom Thurmonds, they would not have been there. Even today there are those who would push us back towards our awful past. Who would have stood against their predecessors – who sought a virtual apartheid in this country – had Robinson failed in 1947?

Inevitable! In 1948, when Thurmond ran on an openly segregationist, racist platform as a third-party candidate for president, he received 1,175,930 votes. In 1968 – after Jackie Robinson and after Malcolm X and after the rise and death of Martin Luther King – George Wallace ran on virtually the same platform and still got 9,901,118 votes.

There was nothing inevitable about the healing of this nation at the center of which was Jack Roosevelt Robinson.

2012 Previews: N.L. Central

F irst of all, this photo of my six-year old niece helping me keep score at the Yankees’ opener doesn’t have a thing to do with the NL Central. It’s just that it represents her first tentative steps towards fandom, and is to my mind fully representative of the rituals of the sport. Just the other day she ceaselessly quizzed her ball-playing older brother about what all the players do. Now she’s trying to figure out what the hieroglyphics represent, and carefully entering abbreviations at my instruction, and asking with delighted amazement: “What does that mean?” (She also insisted we take a walk, I told her we’d go wherever she wanted in the park because she was in charge. “Yes,” she said matter-of-factly. “I know”).

irst of all, this photo of my six-year old niece helping me keep score at the Yankees’ opener doesn’t have a thing to do with the NL Central. It’s just that it represents her first tentative steps towards fandom, and is to my mind fully representative of the rituals of the sport. Just the other day she ceaselessly quizzed her ball-playing older brother about what all the players do. Now she’s trying to figure out what the hieroglyphics represent, and carefully entering abbreviations at my instruction, and asking with delighted amazement: “What does that mean?” (She also insisted we take a walk, I told her we’d go wherever she wanted in the park because she was in charge. “Yes,” she said matter-of-factly. “I know”).

Anyway.

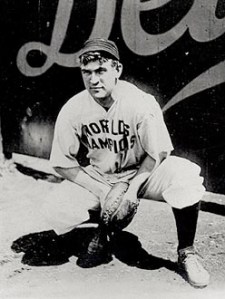

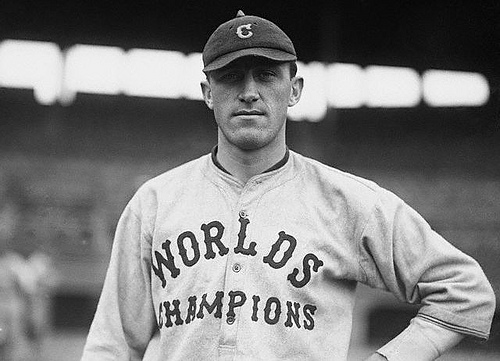

The history of winning the World Series and then altering your uniform the next year to advertise the fact is a star-crossed one. The 2009 Phillies, 2007 Cardinals, and 2005 Red Sox all dipped their toe into the pool and wore special gold trim on their unis for their first one or two home games. The 2011 Giants wore a particularly garish patch all season long. Not one of them repeated their previous year’s triumphs. Go back into history and there are greater calamities still: the 1920 Cleveland Indians overcame the mid-season death of their star infielder Ray Chapman after he was hit in the head by a Carl Mays pitch, then surged past the scandal-ravaged White Sox to grab their first pennant, then won the World Series in large part because of an unassisted triple play by Chapman’s double-play partner Bill Wambsganss.

Next year, Wamby and his teammates dressed in these uniforms: The “Worlds Champions” finished second in 1921, did not seriously contend for the pennant again until 1940 (when they were decimated by an internal player revolt against their manager, earning the players the nicknames “The Crybabies”), didn’t win another Series until 1948, and haven’t won one since.

The “Worlds Champions” finished second in 1921, did not seriously contend for the pennant again until 1940 (when they were decimated by an internal player revolt against their manager, earning the players the nicknames “The Crybabies”), didn’t win another Series until 1948, and haven’t won one since.

The 1927 Cardinals did something similar, although a little less garish, were punished by being crushed in the ’28 Series by the Yankees and the ’30 A’s, but were winners again by 1931.

The 1906 New York Giants wore these modest little outfits, at home and abroad, to celebrate their 1905 title. The Giants fell out of contention in ’06 and ’07, suffered the singular ignominy of the 1908 pennant race and the Merkle Game Controversy in ’08, watched the president of the National League kill himself over that controversy in ’09, didn’t compete in ’10, had their ballpark burn down in ’11, lost the epic series on the Fred Snodgrass “muff” and the Mathewson Wrong Call in ’12, lost another Series in ’13, watched one of their cast-off pitchers lead the last place team past them and to the Series title in ’14, saw the team break up amid gambling rumors in ’15, won 26 in a row and still finished only fourth in ’16, lost the ’17 Series when nobody covered the plate on a rundown from third base, and didn’t come out of it until they won the Series of 1921 and 1922.

I’m not suggesting wearing a uniform devoted more to bragging than team identification caused these calamities, but there is a remarkable amount of trouble associated with teams that merely tinkered with their jerseys after they prevailed. The Cubs went from wearing a simple “C” for their 1907 shirt to a “C” with the “Cubby Bear” nestled inside in 1908. They repeated the title that year, but changed the jerseys to an even more ornate version with “Chicago” spelled vertically down the buttons in ’09, and you might recall what ’09 was the start of for the Cubs.

This is a very very very long way of leading up to this question: This gold-lettered uniform the Cardinals wore Friday? Why did they wear it?

I mean, none of the teams in the National League Central are among baseball’s best this season. They just aren’t and more over, they know it. The division has been drained by the departures of Albert Pujols and Prince Fielder, and despite producing two playoff teams, a World Champion, and a (brief) Cinderella Team, it wasn’t a very good division last year, either.

I’m saying the title might come down to superstition. So why tempt it? I mean, the caps are a little kitschy but the unis are kinda nice. But did you notice that after wearing it for one day, David Freese is already hurt again?

ST. LOUIS has to be the default favorite, but Carpenter’s gone, Wainwright has looked like crap, Berkman’s already suffered two minor injuries that could linger and limit him, or explode and finish him. Among all humans who’ve never managed before, Mike Matheny is probably the 2nd best choice to try to start on the big league stage (Robin Ventura is the 1st), but on what experience will he call if the injuries continue, or the bullpen falters, or Carlos Beltran is sidelined by a scratched nostril,or the Cards all get blood poisoning from the jinxed gold-flecked unis?

Conversely, managerial experience is no automatic indicator of success – ask CINCINNATI. We all love Dusty Baker, one of the great human beings, but his reluctance to trust youngsters has imperiled the career of Aroldis Chapman and is now reflected in his insistence on catching Ryan Hanigan more than Devin Mesoraco. The Ryan Madson injury will only make Dusty even less willing to trust anybody under 35, and I just have to wonder if at some point ownership is going to wake up in the middle of the night and say “we have committed 297 and a half million dollars to the least important quadrant, the right side of the infield” and disappear into the Arctic or something. How on earth is a market like Cincinnati supposed to produce such revenues? Is the news about the Minnesota Twins censored on the internet in the southern half of Ohio? More immediately, there’s a serious question about every Red pitcher (except Chapman, and of course he is used only as the 6th or 7th most important man on the staff).

The Conventional Wisdom suggests Aramis Ramirez was brought to MILWAUKEE to partially offset the loss of Prince Fielder. Nuh-uh. He was brought in to offset the disappearance of Casey McGehee. The Brewers’ swaggering line-up of 2011 looks awfully human with Gamel and Gonzalez and Ramirez in it in 2012. Randy Wolf looks like he’s at the end of the line and the internal dissatisfaction with Zack Greinke is astounding. It’s a very good bullpen, but in any other division this would not be a serious contender.

If Jeff Samardzija and either Bryan LaHair or Anthony Rizzo are for real, CHICAGO may be better than expected, but not much. LaHair has hit well in the NL and Rizzo in the PCL and the obvious move would be to stick LaHair in the outfield, which is already a defensive wasteland, call up Rizzo, and let ‘er rip. Or better yet, off-load David DeJesus or Soriano or Byrd for whatever you could get for them, and give Brett Jackson a shot out there, too. But even if the Cubs hit, past Garza and maybe Samardzija the rest of the rotation is dubious and the bullpen (with the possible exception of rookie Rafael Dolis) will give away a lot of games.

There is a narrow pinhead through which PITTSBURGH might squeeze, and force their way into contention. Revivals from Erik Bedard and A.J. Burnett would give a good bullpen something to save. Andrew McCutchen might blossom into an MVP candidate. Starling Marte might come up next month and hit .330. But masked by the completeness of the Buccos’ post-play-at-the-plate collapse last year was what happened to the fuel of their brief spring in the sun. Jose Tabata vanished. Garrett Jones vanished. Kevin Correia vanished. Jeff Karstens vanished. Inexplicably, Pedro Alvarez vanished and the Pirates insist on still playing him. Midnight struck and Clint Hurdle was suddenly managing a pumpkin farm. Everything that went right last year has to go right again this year – and then some.

There is one bright spot in HOUSTON. If the new owner and Poor Brad Mills (the manager’s new first name) had had to have taken this team into the American League this year, the Astros might’ve gone 30-132. There may be sparkles from Jason Castro behind the plate, Jose Altuve at second, and Brian Bogusevic, J.D. Martinez, and Jordan Schafer in the outfield, but it is plausible that beyond Carlos Lee there might be nobody on this team who hits 15 homers. There certainly aren’t going to be any starting pitchers who win 15 games. Good lord, as I read this to myself, it dawns on me: all the starting pitchers might not win 35 games among them.

2012 N.L. CENTRAL FORECAST:

Man, I have no idea. If these teams were scattered among the other divisions there wouldn’t be a lead-pipe-cinch pennant contender among the six of them. I guess St. Louis will win, with Cincinnati and Milwaukee behind them, and Chicago and Pittsburgh arguing over fourth, and the Astros disappearing from National League history like the Cheshire Cat. The pennant race might prove variable and exciting, but it will not be good, and it will make fans in places like Toronto and Seattle and Miami wish that realignment were a reality.

The 1st Amendment, The 2nd Praising Of Castro, and Five Games

This is revised and updated from the previous post:

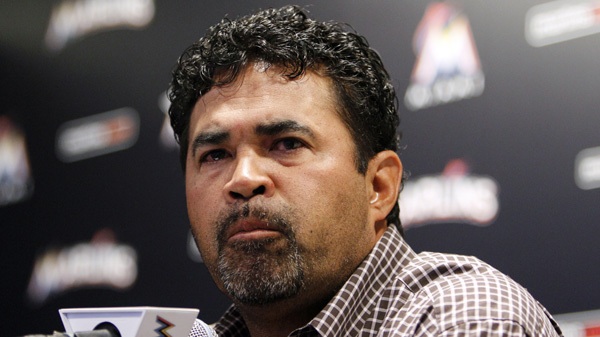

Minutes into his five-game unpaid suspension for having praised Fidel Castro in a community filled with, and animated by, people who think Castro comparable to Hitler, Manager Ozzie Guillen of the Miami Marlins tried to explain that he had hoped to say he was surprised Castro had stayed in power so long, and that someone who had hurt so many over so many years was still alive.

The problem is, it turns out he had made similar remarks about Castro four years ago in which he renounced Castro’s politics and called him a dictator and still ended by saying “I admire him.”

Miami Marlins manager Ozzie Guillen pauses as he speaks at a news conference at Marlins Stadium in Miami, Tuesday April 10, 2012. (AP / Lynne Sladky)

As Rick Telander of the Chicago Sun-Times noted late last night, he interviewed Guillen, the managing the White Sox for a Men’s Journal Q-and-A:

And I asked him this: “Who’s the toughest man you know?’’

His response, which took me by surprise: “Fidel Castro.’’

Why?

“He’s a bull—- dictator and everybody’s against him, and he still survives, has power. Still has a country behind him,’’ Ozzie replied. “Everywhere he goes, they roll out the red carpet. I don’t admire his philosophy; I admire him.’’

That’s an added wrinkle, and it suggests the suspension may be insufficient, at least in terms of length. For some context: over a period of six or seven years, Cincinnati Reds’ owner Marge Schott had said something to offend virtually every group except The Visiting Nurse Association. She said Adolf Hitler “was good in the beginning, but went too far.” She had previously made antisemitic remarks, kept some Nazi trophies from her late husband’s service in World War II (not all that uncommon), bashed gays, blacks, Asians, and supposedly wanted to fire her manager Davey Johnson because he was living with his girlfriend. Major League Baseball – as opposed to just the team acting on Guillen – suspended her for two-and-a-half years and eventually applied enough pressure to get her to sell the franchise.

Flash forward to the remarks to Time Magazine for its newest issue:

“I love Fidel Castro. I respect Fidel Castro. You know why? A lot of people have wanted to kill Fidel Castro for the last 60 years, but that (expletive) is still there.”

As the impeccable Amy K. Nelson live-tweeted from today’s apology news conference:

“Very embarrassed, very sad. I thought the next time I saw this room with this many people, there would be a World Series trophy next to me.”

A predominant response from fans who – correctly, I think – believe we have gotten to the point where we take everything either too seriously or not seriously enough, has been “What happened to Ozzie Guillen’s free speech? What about the 1st Amendment?”

Well – what about it?

Ever read it?

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

That’s the whole thing. In case you think there’s a hidden meaning in there somewhere protecting Ozzie Guillen’s – or your -right to say whatever he wants without consequences from his employers or his community: No.

Translation of the cornerstone of the Bill of Rights, the 1st Amendment to our Constitution to the current mess?

Congress shall make no law abridging Ozzie Guillen’s freedom of speech.

His bosses? They can abridge it all they want.

Ironically, the heavy-handedness of local politicians trying to capitalize on the situation may serve to protect Ozzie. The Chairman of the Board of Commissioners of Miami-Dade wants Guillen to resign, or to be fired. “To say you respect Fidel Castro,” writes Joe A. Martinez, “suggests he also respects dictators such as Hugo Chavez, Daniel Ortega, Adolf Hitler and Sadam Hussein.”

Not quite. Ozzie is guilty of praising (or admiring, or being astonished at, or being appalled by, depending on when you ask him) Castro’s longevity, in much the same kind of way he would’ve tried to praise Jamie Moyer if he threw a 4-hit shutout against the Marlins. But there are third rails, and in South Florida, Castro is viewed as the destroyer of lives, the ruination of the homeland, the man who separated families, tortured opponents, the man who sent would-be refugees to drown or be eaten by sharks, and sent a country back to 1947.

There are survivors, and the relatives of those who didn’t survive, and one of the things they don’t want to hear is that there’s anything good about Castro. And I can’t blame them. You can’t view this exclusively from your own perspective. You need to remember that much of the geographical area the Marlins represent view what has happened to Cuba since 1959 the way Israel views its more belligerent neighbors – or worse.

The usually hip Deadspin was particularly tone-deaf on this:

I’m not Cuban, nor have I ever been to Miami so I don’t know how this played out among that population, but I would just say this…

No, don’t. The 1st Amendment doesn’t protect you either, Bud.

The question remaining is: Is five games sufficient. A local anti-Castro group said yesterday it planned to picket and protest the team until Guillen is out, or Castro leaves office, or both – In which case Ozzie had better hope he has completely misjudged the dictator’s longevity. One assumes a serious suspension would tamp down the fire pretty quickly.

There are a lot of arguments here, but the one to leave out involves wrapping Guillen in the 1st Amendment. It might be nice (or it might be disastrous) if we all had some kind of private immunity from controversial statements, but we clearly don’t.