Tagged: Gil Hodges

Of Hype And Baseball Cards In The Attic (Updated)

Sometimes – whether you merit it or not – you seed the Publicity Storm Cloud just right with the chemicals and you get eight inches of rain.

Such it was yesterday when a respected memorabilia auction house put out a story about the discovery of some hundred-year old baseball cards in an attic in Ohio. I have a little less than 400,000 followers on Twitter and it feels like half of them sent me a link, wondering if I would be buying what each and every article described as three million dollars worth of cards. As near as I can tell, the story was picked up by ABC, CBS, NBC, ESPN, Fox, AP, Forbes Agence France Presse, TASS, and Pravda. As I washed my face before bed last night and flipped on the radio, the story was on the CBS hourly newscast.

I’ve dealt with the auctioneers – Heritage – for years with nothing but professional results, and I’m accusing them of nothing but professional success here, but boy oh boy oh boy did they hype this thing.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Finding 1909-10 baseball cards in pristine condition in an attic at Defiance, Ohio, is a wonderful story and the cards are worth a lot of money. But comparisons to unique artwork (“It’s like finding the Mona Lisa in the attic,” said the finder) and the three-million dollar pricetag are ludicrous.

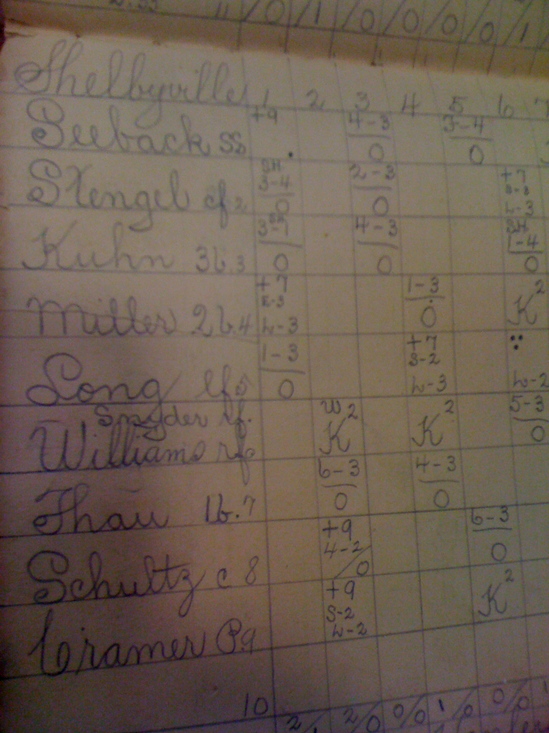

Here are some of the cards, and then I’ll explain why the pricetag is nonsensical:

There are 30 cards in the set, issued by an anonymous candy manufacturer during the baseball card craze of 1909-11. Labeled within our hobby for cataloging purposes as “E-98” (the “E” is for “Early Candy and Gum”) the cards are scarce compared to other more plentiful issues of the time (yet there are 15 of them available right now, in lesser shape, on eBay). They also just aren’t that popular. In an era in which the candy companies produced extraordinarily beautiful lithographs of players stylized to look like Greek Gods with blazing sunsets behind them, E-98’s are pretty bland colorized black-and-white images set against one-color backgrounds. The set is also full of careless errors (if you look at the card of “Cy” Young, lower left, you’ll notice it shows a lefthanded pitcher. Cy, who only won 511 career games, was a righthander. The photo actually depicts a very obscure contemporary named Irv Young).

Here’s what I mean about relative attractiveness. The Mathewson and the Wagner below are from the E-95 set issued by Philadelphia Caramel in 1909. Find me 700 copies of them in superb condition and we’re talking.

:

Nevertheless, baseball card price guides agree that a full set of all 30 E-98 cards should be valued at about $125,000 in near perfect condition. The 37 cards that the auction house, Heritage, plans to sell next month, are the best of the bunch, real beauties with sharp corners, the kind investors love.

Nevertheless, baseball card price guides agree that a full set of all 30 E-98 cards should be valued at about $125,000 in near perfect condition. The 37 cards that the auction house, Heritage, plans to sell next month, are the best of the bunch, real beauties with sharp corners, the kind investors love.

The problem is that there’s only one thing that investors react to more than beautifully conditioned old cards. That would be the sudden “find” of a large lot of previously hard-to-find cards.

From the time it came out in 1953 or 1954, a Dormand Postcards issue of Gil Hodges of the Brooklyn Dodgers was wildly scarce. In the days when regular cards from the series fetched a dollar or two and even a Mickey Mantle cost only $5 or $10, Hodges was “worth” $400. Then a few years ago somebody found a stack of them. I mean, like 750 of them. Like, however many they made and didn’t distribute for whatever reason back in the ’50s. Right now on eBay you can get your average Dormand postcard for $25 to $45. Hodges? Well, you can buy-it-now for $750. That’s $750 for 42 copies of the Hodges card (some poor guy, meanwhile, is still trying to sell his one pristine-looking Hodges for $2,000).

If you read the entire story of the “attic find” in Ohio you’ll notice that what they discovered wasn’t just 37 old cards, but 700 of them. The family and the auction house aren’t saying specifically what the rest of them are, but the way these things work, if there weren’t a lot more of the E-98 cards (presumably in lesser condition) than they’d be auctioning them off, too. If they were more valuable, or more intriguing, or just from a more collected or beloved set of cards, they’d be publicizing them.

So, congrats to the owners of the “find.” The estimate for what an auction next month at the national collectors’ gathering in Baltimore – $500,000 – might be a little high, but it’s probably in range. Investors will invest in anything, especially if they’ve read about it in the news. But even some of the news articles indicate that there are less than 700 of these E-98’s registered and encased in plastic (as in the illustration) with an unknown larger supply in “raw” (that is, not encapsulated) condition. If you introduce 700 new ones into the market, the price will initially go up, and then way, way down.

The family and the auction house have a stack of 700+ cards from a set nobody really collects and which investors might begin to doubt.

Don’t forget to wave to the Gil Hodges Dormand Postcard when you pass it.

UPDATE 5 PM EDT: A tweeter raises an important point. Javier Cepero writes: “Doesn’t the guy have a Honus Wagner 10 rated card?”

Yes. But not the Honus Wagner. The Honus Wagner – from the American Tobacco Company 1909 set called “T-206” has been sold for $3,000,000 by itself (in perfect, albeit altered condition) down to the $300,000-$400,000 range for the crappier ones.

“The” Wagner is on the right. “My” Wagner meets baseball historian/Braves pitcher Tim Hudson last year, in the middle. The E-98 Wagner is on the right.

“The” Wagner is on the right. “My” Wagner meets baseball historian/Braves pitcher Tim Hudson last year, in the middle. The E-98 Wagner is on the right.

Name Dropping Herman Long

Had the pleasure of joining Brian Kenny on MLB Network’s Clubhouse Confidential yesterday (more on that below) and as we batted back and forth the necessity of electing Gil Hodges to the Hall of Fame, Brian mentioned that if he gave me a chance I could drop a lot of 19th Century Cooperstown-worthy players. I had time to say only “look up Herman Long.”

I’ll detail his Hall credentials in a moment. But first: for all of the weird HOF elections of the first 75 years, he is in the middle of the weirdest. Take a look at the results from the first-ever Veterans’ Committee vote, conducted in 1936:

- Buck Ewing 39.5 Votes, Elected 1939

- Cap Anson 39.5 Votes, Elected 1939

- Wee Willie Keeler 33 Votes, Elected 1939

- Cy Young 32.5 Votes, Elected 1937

- Ed Delahanty 21.5 Votes, Elected 1945

- John McGraw 17 Votes, Elected 1937

- Old Hoss Radbourn 16 Votes, Elected 1939

- Herman Long 15.5 Votes

- King Kelly 15 Votes, Elected 1945

- Amos Rusie 11.5 Votes, Elected 1977

- Hughie Jennings 11 Votes, Elected 1945

- Fred Clarke 9 Votes, Elected 1945

- Jimmy Collins 8 Votes, Elected 1945

- Charles Comiskey 6 Votes, Elected 1939

- George Wright 6 Votes, Elected 1937

So there were 78 ballots, 60 different players got votes, half of them eventually wound up in the Hall, but the guy who got the eighth most, who finished ahead of 23 future Hall of Famers, not only never made it but never again got significant support? I mean, in the 1937 Veterans’ Committee ballot, Long got one vote.

Something is very, very strange here. I mean, while we think of the stars of the 19th Century and the early 20th as having played in some kind of baseball version of the Pleistocene era, consider who the 1936 voters were. If this were January, 1936, Bob Costas would’ve made his NBC baseball debut in 1907, I would’ve covered my first World Series in 1900, Peter Gammons would’ve broken in with The Boston Globe in 1893, and Tim McCarver would’ve started with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1883.

In short, the 78 members of the Veterans Committee of 1936 saw most of the antediluvian names on that ballot play either professionally or as kids (let’s just play with that again: if this were 1936 I’d have seen my first MLB game in 1891 and I believe Peter’s first would’ve been in 1882). These guys thought of Herman Long in the same breath with the most famous player of the 19th Century (King Kelly), the man who won 59 games in one season (Hoss Radbourn), and the man who played or managed 14 pennant winners (John McGraw). For further context, there were six players to whom the first Veterans voters gave exactly one vote each, who wound up in Cooperstown and to some degree in the baseball public’s awareness, like 342-game winner Tim Keefe and the inventor of the curveball Candy Cummings. And Herman Long got 15 times as many votes.

So who was this guy?

Derek Jeter is the Yankee shortstop now, but Long was the first. His 1903 Breisch-Williams baseball card; the photo shows him from Boston circa 1899

Herman Long was the great shortstop of the Boston Beaneaters’ dynasty of the 1890’s. He produced four consecutive years of an OPS of .800 or higher, had two 100-RBI seasons, six 100-Run seasons, and in a time without home runs, he hit 91 of them over 13 seasons including a dozen in each of two years. He stole 537 bases (that’s still 30th all-time) and scored 1,456 runs (77th all-time). In that measure of what an individual player’s offense and defense was “worth” to his team, “WAR,” Long finished with 44.6 (his Hall of Fame teammate, third baseman Jimmy Collins, finished at 53, and his Hall of Fame teammate, centerfielder Tommy McCarthy, finished at just 19). And despite having made more errors than anybody else in history, he has the 122nd best Defensive WAR+ among all position players ever. Boston’s two spurts – at the beginning and end of the 1890’s – produced five pennants and Long was the shortstop on all of the teams.

His nickname was “The Flying Dutchman.” When they began to use it late in the 1890’s for a kid named Honus Wagner, it was a tribute to Herman Long. More trivially, he would later play only 22 games there, but he was the first shortstop of the New York Yankees (then the Highlanders).

Is Long a Hall of Famer? I’m not sure. But he was considered the 8th best player among the “Old Timers” in 1936, and then fell into a black hole. It wasn’t even a matter of public scandal or diminished rotation – Long had been dead since 1909. He certainly merits consideration.

Remind me to tell you later about Bobby Mathews.

SPEAKING OF OLD TIMERS

Returning to the topic of my visit to MLB Network, if you didn’t know, that’s where my erstwhile employers MSNBC were headquartered from 1996 until October, 2007. I worked in this very building from September of ’97 through December of ’98, and then again from February of ’03 until we moved out. Yesterday was my first day back and it was mind-blowing. Baseball invested a reported $54,000,000 to upgrade the facility with rebuilt studios and state-of-the-art technology.

But they changed almost nothing else.

Not the carpets. Not the desks. Not the chairs. Not the make-up rooms. Not the cubicles. Not where the large clusters of desks are. Not the cafeteria. Not the offices. Not the office door plates. Not the “Employees Must Wash Hands” signs in the bathrooms.

Going into it was like one of those dreams you’ve probably had where you walk into some place totally familiar to you – your childhood home, or where you live now, or go to work, or school – and in the middle of it your unconscious has placed a nuclear reactor or a jungle or something else utterly incongruous, without changing even one other thing.

You think I’m kidding? My old offices, the one from 2003 and the one from 1997, are still offices, with the same doors, windows, nameplates, and televisions. The newer of them is occupied by an old colleague of mine from Fox Sports named Mike Konner, and to my amazement I found that on what is now his wall was a poster from MSNBC’s 2004 Campaign Coverage. I remembered this one distinctly, because there was controversy over some of the people shown in the back row (somebody wasn’t under contract, or somebody was left out, or something), and the thing was immediately replaced by a revised version with somebody else’s body swapped in. As I saw it hanging on Mike’s wall I remembered I had left the rare “uncorrected” version in a pile of junk when I left.

So why was it on Konner’s wall? I asked Mike where he found it. “It was here when we moved in. In a pile of junk.”

Every time I think of him saying that, I laugh. The poster has been in that tiny office since 2004.

Hey Hey!

Thank God.

A year too late for him to enjoy it, 30 years past the day he should’ve been selected, the Baseball Hall of Fame Veterans’ Committee has finally elected the most deserving candidate not in Cooperstown, Ron Santo.

For those who doubt, here is my statistical analysis of the five leading playing candidates:

The simplest tool for judging a player against his contemporaries is, I think, the most overlooked one – exact comparisons, from a guy’s debut season through his final year.

Awards are useful, especially as an indicator of greatness – in Ron Santo’s case, the five straight NL Gold Gloves 1964-68 pretty much confirm his defensive prowess – consider the one from 1964, when Cardinals’ third baseman and defensive hero Ken Boyer was MVP, but Santo still won the Glove.

The hardware is nice. But statistics are better.

In short, in his era, from when he came up with the Cubs in 1960 through his last year with the White Sox in 1964, Ron Santo was one of the top ten hitters in all of baseball.

Santo was fifth in RBI in his era.

Santo was ninth in Runs in his era.

Santo was tenth in Homers in his era.

Santo was tenth in Hits in his era.

There are 17 players besides Santo on these four lists of the top ten offensive producers of the 1960’s. Only four men on all four lists: Aaron, Frank Robinson, Billy Williams – and Santo. Even the three men who are only on three lists, compared to Santo’s four, are all in Cooperstown already.

Needless to say, only one other full-time Third Baseman (Brooks Robinson) shows up on any of the four lists – and he, only twice. Part-timer Killebrew is on three of them: handily ahead of Santo in one (HR), behind Santo in another (R), and just two spots and only 74 RBI ahead of him in the third.

You can’t ask more of a man than to produce those kinds of numbers against his direct contemporaries: what he did while he played, compared to what everybody else did while he played, is all that he can be judged on. But it focuses exactly where a player stood against his peers.

By the way, if you want to be more generous to Santo, and judge him from his first full year as a regular (1961) through his last year as an everyday player (1973) he looks better still: he holds at fifth in RBI, but moves up one spot each in Runs (eighth), Homers (ninth), and Hits (9th).

I had Gil Hodges second.

Again, what he did in his time tells me what I need to know. Here is a list, updated through May 5, 1963 – the date Gil Hodges played his last game in the major leagues.

All-Time MLB Home Run Leaders (RH Batters):

1. Jimmie Foxx 534

2. Willie Mays 373

3. Gil Hodges 370

4. Ralph Kiner 369

5. Joe DiMaggio 361

6. Ernie Banks 340

7. Hank Greenberg 331

8. Hank Aaron 307

8. Al Simmons 307

10. Rogers Hornsby 301

By the way, on the all-time homer list, lefties and righties both, Hodges had just been knocked out of 10th place, by Mays (373 to 370). The game changes. Still, it is extraordinary that Hodges’ home run performance measured against all his contemporaries and predecessors, is pretty much ignored.

Hodges’ career spanned 20 calendar years, but he only played regularly from 1948 to 1959. In “his” era, Hodges was second in MLB in homers (344, to Duke Snider’s 354), second in RBI (tied with Berra at 1136, behind Musial’s 1226), fourth in Runs, and seventh in Hits. Hodges is often dismissed as a “Home Park Homer Hitter.” In fact in his ten years at Ebbets Field he averaged only 4.60 homers a year more in Brooklyn than on the road. For comparison, Duke Snider, in the Hall since 1980, averaged 4.56 homers a year more in Brooklyn than on the road.

It is also of note that Hodges hit 27 or more homers in eight consecutive seasons, drove in 102 or more runs seven years in a row, and the first baseman on two World’s Champions and four more NL champs.

Haven’t even mentioned Hodges the manager (1969 Miracle Mets) nor Hodges the Man (I have never, ever talked to anyone who knew him who didn’t revere him.

Third on my list? Luis Tiant. Bill James hit the nail on the head: Luis Tiant is Catfish Hunter with poorer marketing.

Statistical doppelgangers are often either coincidental, superficial, or irrelevant because the players are of different historical eras. Not Hunter and Tiant. They pitched side-by-side in the same league for fifteen seasons, in the same division for six, and were teammates for a year. And they look like twins in a dozen key stats:

Statistic Hunter Tiant

Starts 476 489

Complete Games 181 187

Shutouts 42 49

Innings 3449.1 3486.1

Home Runs 374 346

Wins 224 229

Losses 166 172

ERA 3.26 3.30

Run Support 4.30 4.46

20-Win Seasons 5 4

Sub 3.00 ERA Seasons 5 6

‘Wins Above Team’ 20.2 20.6

That’s right: Tiant made 13 more starts, won five and lost six more games, threw seven more shutouts, and finished with an ERA 0.04 higher, than Hunter. Otherwise, they share a virtually identical statistics.

Where they deviate leaves open the question of which was the better pitcher. Tiant had 404 more strikeouts, but 150 more walks. Hunter twice led the AL in wins, which Tiant never did. Tiant twice led it in shutouts, which Hunter never did. Tiant twice led it in ERA, which Hunter did once.

Hunter’s big advantage? He made 22 ALCS and World Series starts to Tiant’s five. He was seen on the biggest stage, by fans and reporters alike, for seven of eight Octobers. Tiant had only one shot at such impact.

Beyond the Hunter comparisons, in the match-him-against his era numbers, Tiant was ninth in wins, tenth in K’s, twelfth in ERA, 1964-80 (even though in five of those seasons he did not make even 20 starts).

And there is one more remarkable and overlooked statistic. Two of Tiant’s six sub-3.00 ERA seasons were actually sub-2.00 ERA seasons. Since 1920, only 29 pitchers have had a seasonal ERA under 2.00. Koufax did it three times, and the other four did it twice: Roger Clemens, Greg Maddux, Pedro Martinez – and Tiant.

Fourth – and he’s right below Tiant – is Minnie Minoso. He’s kind of damned by the overall quality of his play: superb at a lot of contradictory things, not extraordinary at any one of them:

Who were the top five hitters during Minnie Minoso’s 13 seasons as a Major League regular, 1951-63? Keep it to the guys who averaged at least 475 at bats a year and here’s the headline: one of them was Minnie Minoso.

Highest Batting Average 1951-1963 (Minimum 6175 AB)

1. Stan Musial .319

2. Willie Mays .315

3. Richie Ashburn .309

4. Harvey Kuenn .307

5. Minnie Minoso .299

Note please, that performance included eight .300 seasons. It’s impressive stuff, but below is my favorite Minoso stat:

Highest Slugging Percentage 1951-1963 (Minimum 6175 AB)

1. Willie Mays .588

2. Stan Musial .543

3. Eddie Mathews .535

4. Minnie Minoso .461

5. Harvey Kuenn .417

The slugging number is especially astounding given that Minoso only hit 184 homers in those 13 years (28th in the era). Without being a real longball threat, he still places 8th in total bases in the span, and 9th in RBI.

Most Runs Scored, 1951-1963

1. Mickey Mantle 1381

2. Willie Mays 1258

3. Eddie Mathews 1220

4. Nellie Fox 1142

5. Minnie Minoso 1130

Seeing my point here? Pick a category, and Minoso shows up on it:

Most Stolen Bases, 1951-1963

1. Luis Aparicio 309

2. Willie Mays 248

3. Maury Wills 236

4. Minnie Minoso 205

5. Billy Bruton 193

Minoso is also fifth in hits in the era, second in doubles (behind Musial, ahead of Mays), fourth in triples, led the A.L. in hit-by-pitch ten times, won three Gold Gloves – and all this even the color line and circumstance kept him from becoming a major league regular until he was at least 28 years old.

My fifth guy out of the group is just a notch below. I love Jim Kaat and I think he belongs (as does Tommy John). I mentioned contemporaries Hunter and Tiant looking separated-at-birth. Jim Kaat and Robin Roberts are unlikely statistical twins who overlapped by only seven full seasons:

Statistic Kaat Roberts

Starts 625 609

Innings 4530.1 4688.2

Wins 283 286

Losses 237 245

Strikeouts 2461 2357

Walks 1083 902

ERA 3.45 3.41

10+ Win Season Streak 15/15 16/17

Roberts got to Cooperstown quickly because of the fact he reeled off six consecutive brilliant seasons, and despite of the fact that after the age of 28, only once did he finish more than three games above .500 in his final eleven seasons.

By contrast, Kaat won 18 as a 22-year old, slumped for a year, then starting in 1964 reeled off 17, 18, and then 25. Eight and nine years later he would produce consecutive seasons of 20 and 21 wins. As Bill James pointed out, if like Roberts, Kaat had bunched his great years instead of scattering them, he might’ve been elected in the ‘90s. As it is, he is still 31st all-time in victories — eighth all-time among lefties:

Wins, Lefthanded Pitchers:

1. Warren Spahn 363

2. Steve Carlton 329

3. Eddie Plank 326

4. Tom Glavine 305

5. Randy Johnson 303

6. Lefty Grove 300

7. Tommy John 288

8. Jim Kaat 283

9. Jamie Moyer 267

10. Eppa Rixey 266

11. Carl Hubbell 253

12. Herb Pennock 241

There are only eight active lefties with more than 100 wins, and of them, only CC Sabathia (176) is younger than 32. Kaat is also 10th in strikeouts by lefties. Kaat’s victory total has been criticized as “padded” by his five years as a reliever and spot starter. But subtract those seasons and his career won-lost improves to 261-217, he remains in the top 10 among lefties, and still has better won-losts than Ted Lyons and Eppa Rixey (and is just behind Red Faber).

Lastly, the 16 consecutive Gold Gloves are almost a cliché. We don’t stop to think that the first of them was won when Kitty was 23, and the last when he was 38 – and that the streak stretched through five presidential administrations and three expansion drafts.

Just to show my math, here are the Homer, Runs Scored, RBI, and Hit lists from ’60-’74 that back-up Santo’s greatness:

Most RBI, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Hank Aaron, 1585

2 Frank Robinson, 1412

3 Harmon Killebrew, 1405

4 Billy Williams, 1351

5 Ron Santo, 1331

6 Brooks Robinson, 1217

7 Willie Mays, 1194

8 Willie McCovey, 1190

9 Carl Yastrzemski, 1181

10 Orlando Cepeda, 1164

Most Runs Scored, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Hank Aaron, 1495

2 Frank Robinson, 1390

3 Billy Williams, 1306

4 Lou Brock, 1303

5 Willie Mays, 1285

6 Carl Yastrzemski, 1240

7 Pete Rose, 1217

8 Vada Pinson, 1177

9 Ron Santo, 1138

10 Harmon Killebrew, 1131

Most Homers, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Hank Aaron, 554

2 Harmon Killebrew, 506

3 Frank Robinson, 440

4 Willie McCovey, 422

5 Willie Mays, 410

6 Billy Williams, 392

7 Frank Howard, 380

8 Norm Cash, 373

9 Willie Stargell, 346

10 Ron Santo, 342

(Note: 11th was Orlando Cepeda, 327)

Most Hits, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Billy Williams, 2505

2 Hank Aaron, 2463

3 Brooks Robinson, 2459

4 Vada Pinson, 2455

5 Lou Brock, 2388

6 Pete Rose, 2337

7 Roberto Clemente, 2318

8 Willie Davis, 2271

9 Carl Yastrzemski, 2267

10 Ron Santo, 2254

(Note: 11th was Frank Robinson, 2220)

The Ironies Of The Late Duke Snider

It is, as ever, summed up perfectly by Vin Scully:

“Although it’s ironic to say it, we have lost a giant.”

Beyond the sadness of the passing of The Duke of Flatbush, Edwin Donald Snider, is the reminder that his career was filled with irony. As the top Dodger prospect of the late ’40s he was considered a temperamental bust. By the time of his passing today he was considered one of the game’s most personally revered gentlemen, and long before, by the time the Dodgers left Brooklyn, he was considered one of the elder statesmen of the sport, his prematurely-silver hair and hint of sadness in the eyes seemingly reflecting the tragedy that was the move of the franchise.

Therein too lay an irony. Duke Snider was a Southern Californian through and through. Alone among the key Brooklyn Dodgers, he was going home to Los Angeles. And yet he expressed only sadness and regret about that, and during his brief coda season with the Mets in 1963, was welcomed home to New York more loudly than any other of the “exes” – Casey Stengel included.

There is also something tremendously ironic about the iconic status included in Terry Cashman’s “Talkin’ Baseball” song. Despite the premise of “Willie, Mickey, and The Duke,” the Baseball Writers needed eleven tries to get his election to the Hall of Fame right. In his first year of eligibility, Snider got just 51 votes – a stunning 17 percent. As late as 1975 he was under 40%.

The writers dismissed Snider, as they did nearly all the Dodger offensive stars, because they felt Ebbets Field provided some kind of extraordinary advantage and because the Dodgers lost so many ultimate games. Gil Hodges is still – criminally – not in Cooperstown in part because of this prejudice. In point of fact, Snider hit just 37 more homers in Brooklyn than on the road in his Ebbets Field years (discounting partial seasons, that’s an average of four or at most five more a year – a meaningless statistical variable).

Hodges has still not gotten his due; Snider and Pee Wee Reese struggled for it; Carl Furillo has never been taken seriously. It is amazing to contemplate that Snider’s Dodgers were somehow penalized because between 1946 and 1956 they won only the one World Series, while losing five of them, and losing two special NL playoffs, and losing yet another year (1950) on the last day of the season. That was painful stuff to be sure, but what it meant was, that for every year for a decade (excepting 1948) the Dodgers gave their fans, at worst, a team that made it to “the final four” – and with key parts of the Brooklyn franchise still at work in Los Angeles, added World Championships in 1959, 1963, and 1965.

This is a time for condolence and mourning and I don’t mean to at all take away from that. It’s just that the passing of a great and good baseball man like Duke Snider reminds me that the injustice of the undeserved undermining of the reputation of a player, or a team, should also not be forgotten.

Cooperstown Path Cleared For Steinbrenner, Miller

George Steinbrenner is now eligible to be elected to the Hall of Fame as early as this December.

Hall of Fame Board of Directors Restructures

Procedures for Consideration of

Managers, Umpires, Executives and Long-Retired Players

(COOPERSTOWN, NY) – The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Board of Directors has restructured the procedures to consider managers, umpires, executives and long-retired players for election to the Hall of Fame.

The changes, effective immediately, maintain the high standards for earning election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The voting process will now focus on three eras, as opposed to four categories, with three separate electorates to consider a single composite ballot of managers, umpires, executives and long-retired players.

“The procedures to consider the candidacies of managers, umpires, executives and long-retired players have continually evolved since the first Hall of Fame election in 1936,” said Jane Forbes Clark, chairman of the board for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “Our continual challenge is to provide a structure to ensure that all candidates who are worthy of consideration have a fair system of evaluation. In identifying candidates by era, as opposed to by category, the Board feels this change will allow for an equal review of all eligible candidates, while maintaining the high standards of earning election.”

The Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors includes:

|

Jane Forbes Clark (chairman) |

Robert A. DuPuy |

Jerry Reinsdorf |

Allan H. “Bud” Selig |

|

Joe Morgan (vice chairman) |

William L. Gladstone |

Brooks C. Robinson |

Edward W. Stack |

|

Kevin S. Moore (treasurer) |

David D. Glass |

Frank Robinson |

|

|

Paul Beeston |

Leland S. MacPhail Jr. |

Dr. Harvey W. Schiller |

|

|

William O. DeWitt Jr. |

Phil Niekro |

G. Thomas Seaver |

|

� Eras: Candidates will be considered in three eras — Pre-Integration (1871-1946), Golden (1947-1972) and Expansion (1973-1989 for players; 1973-present for managers, umpires and executives).

� Candidates: One composite ballot of managers, umpires, executives and long-retired players will be considered in each era. The Expansion Era ballot will feature 12 candidates, while the Golden and Pre-Integration era ballots will feature 10 candidates. Candidates will be classified by the eras in which their greatest contributions were recorded.

� Electorates: A Voting Committee of 16 members for each era will be appointed by the Board of Directors annually. Each committee will be comprised of Hall of Fame members, major league executives, and historians/veteran media members. Any candidate who receives at least 75% of ballots cast will earn election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

� Frequency of Elections: An election will be held annually at the Winter Meetings. The Eras will rotate, with the Expansion Era Committee to vote onDecember 5, 2010 at the Winter Meetings in Orlando, Fla. The Golden Era committee will meet at the Winter Meetings in 2011 and the Pre-Integration Era Committee will vote on candidates at the 2012 Winter Meetings.

� Screening Process: The BBWAA-appointed Historical Overview Committee will devise the ballots for each era. The Historical Overview Committee currently consists of 10 veteran members: Dave Van Dyck(Chicago Tribune); Bob Elliott (Toronto Sun); Rick Hummel (St. Louis Post-Dispatch); Steve Hirdt (Elias Sports Bureau); Bill Madden (New York Daily News); Ken Nigro (formerly Baltimore Sun); Jack O’Connell (BBWAA secretary/treasurer); Nick Peters (formerly Sacramento Bee); Tracy Ringolsby (FSN Rocky Mountain); and Mark Whicker (Orange County Register).

� Eligible candidates:

� &n

bsp; Players who played in at least 10 major league seasons, who are not on Major League Baseball’s ineligible list, and have been retired for 21 or more seasons;

� Managers and umpires with 10 or more years in baseball and retired for at least five years. Candidates who are 65 years or older are eligible six months following retirement;

� Executives retired for at least five years. Active executives 65 years or older are eligible.

Timetable for Upcoming Elections

DATE

|

ACTIVITY |

WHO |

|

October 2010 |

The Expansion Era (1973-1989) ballot is devised and released.

|

The BBWAA Historical Overview Committee.

|

|

December 2010

|

Meeting and Vote on Expansion Era (1973-1989) ballot at the Winter Meetings.

|

A Committee of 16 individuals comprised of Hall of Fame members, veteran writers and historians, appointed by the Board of Directors. |

|

July 24, 2011 |

Induction of Expansion Era Committee selections, if anyone elected.

|

|

|

October 2011 |

The Golden Era (1947-1972) ballot is devised and released.

|

The BBWAA Historical Overview Committee.

|

|

December 2011

|

Meeting and Vote on Golden Era (1947-1972) ballot at the Winter Meetings.

|

A Committee of 16 individuals comprised of Hall of Fame members, veteran writers and historians, appointed by the Board of Directors. |

|

July 29, 2012 |

Induction of Golden Era Committee selections, if anyone elected.

|

|

|

October 2012 |

The Pre-Integration Era (1871-1946) ballot is devised and released.

|

The BBWAA Historical Overview Committee.

|

|

October 2012

|

Meeting and Vote on Pre-Integration Era (1871-1946) ballot at the Winter Meetings.

|

A Committee of 16 individuals comprised of Hall of Fame members, veteran writers and historians, appointed by the Board of Directors. |

|

July 28, 2013 |

Induction of Pre-Integration Era Committee selections, if anyone elected.

|

|

The Nine Smartest Plays In World Series History

Inspired by Johnny Damon’s double-stolen base in Game Four on Sunday, I thought it was time to salute a part of the game rarely acknowledged and even more rarely listed among its greatest appeals to the fan. What they once quaintly called “good brain-work”: the nine Smartest Plays in World Series History.

We’ll be doing this on television tonight, illustrated in large part with the kind help of the folks behind one of the most remarkable contributions ever made to baseball history, The Major League Baseball World Series Film Collection, which comes out officially next week, and which, as the name suggests, is a DVD set of all of the official “films” of the Series since ex-player Lew Fonseca started them as a service to those in the military in 1943. The amount of baseball history and the quality of the presentation (the “box” is by itself, actually a gorgeous Series history book) are equally staggering.

We start, in ascending order, with a famous name indeed, and Jackie Robinson’s steal of home in the eighth inning of the first game of the 1955 World Series. It is perhaps the iconic image of the pioneer player of our society’s history, but it was also a statement in a time when the concept was new. Ironically, the Dodgers were losing 6 to 4 when Robinson got on, on an error, moved to second on a Don Zimmer bunt, aggressively tagged up on a sacrifice fly.

Robinson was at third, but up for the Dodgers was the weak-hitting Frank Kellert. And, after all but taunting pitcher Whitey Ford and catcher Yogi Berra of the Yankees, Jackie seized the day, and broke for the plate. No catcher has more emphatically argued a call, and no moment has better summed up a player, his influence, or the changes he would bring to the game.

Ironically, that was the last run the Dodgers would score and they would lose the game. But the steal set a tone for a different Brooklyn team than the one which had tried but failed to outslug the Yankees in their previous five World Series meetings. The Dodgers would win this one, in seven games.

The eighth play on the list is another moment of base-running exuberance. In a regular season game in 1946, Enos “Country” Slaughter, on first base, had been given the run-and-hit sign by his St. Louis Cardinals’ manager Eddie Dyer. Slaughter took off, the batter swung and laced one into the outfield. As Slaughter approached third base with home in his sights, he was held up by his third base coach Mike Gonzalez. Slaughter complained to his skipper. He knew better than Gonzalez, he told Dyer, whether or not he could beat a throw home. Dyer said fine. “If it happens again and you think you can make it, run on your own. I’ll back you up.”

It indeed happened again – and in the bottom of the eighth inning of the seventh game of the 1946 Series! The visiting Red Sox had just tied the score at three, but Slaughter led off the inning with a single. Manager Dyer again flashed the run-and-hit sign, and Harry “The Hat” Walker lined Bob Klinger’s pitch over shortstop for what looked to everybody like a long single.

Everybody but Slaughter. He never slowed down. He may never have even seen third base coach Gonzalez again giving him the stop sign. When Boston shortstop Johnny Pesky turned clockwise to take the relay throw from centerfielder Leon Culberson, and, thus oddly twisted, could get little on his throw to the plate – Slaughter scored, the Cardinals led, and, an inning later, were World Champions.

The Red Sox should’ve seen it coming. Long before Pete Rose, Slaughter ran everywhere on the field, to the dugout and from it, on walks, everywhere. He said he had learned to do it in the minor leagues, when as a 20-year old he walked back from the outfield only to hear his manager say “Hey, kid, if you’re tired, I’ll get you some help.”

That manager was Eddie Dyer – the same guy who a decade later would encourage Slaughter to run any and all red lights.

The particulars of the seventh smartest play in Series history are lost in the shrouds of time: the 1907 Fall Classic between the Tigers and Cubs. This was the Detroit team of the young and ferocious Ty Cobb, but its captain was a veteran light-hitting third baseman named Bill Coughlin. In the first inning of the second game, Cubs’ lead-off man Jimmy Slagle walked, then broke for second base. Catcher Fred Payne’s throw was wild and Slagle made it to third. Coughlin knew the Tigers were in trouble.

There are two ways to do what Coughlin did next; we don’t know which he used. Later third basemen like Matt Williams were known to ask runners to step off the base so he could clean the dirt off it. Others, through nonchalance or downright misdirection, would convince the runner that they no longer had the ball. Which one Coughlin did, we don’t know. The Spalding Base Ball Guide for 1908 simply described it as “Coughlin working that ancient and decrepit trick of the ‘hidden ball,’ got ‘Rabbit’ Slagle as he stepped off the third sack. What the sleep of Slagle cost was shown the next minute when Chance singled over second.”

Coughlin snagged Slagle with what is believed to be the only successful hidden ball trick in the history of the Series.

Sixth among the smartest plays is another we will not likely see again. The New York Mets led the Baltimore Orioles three games to one as they played the fifth game of the 1969 World Series. But the favored Birds led that game 3-zip going into the bottom of the sixth. Then, Dave McNally bounced a breaking pitch at the feet of Cleon Jones of the Mets. Jones claimed he’d been hit by the pitch, but umpire Lou DiMuro disagreed – until Mets’ skipper Gil Hodges came out of the dugout to show DiMuro the baseball, and the smudge of shoe polish from where it had supposedly hit Jones. DiMuro changed his mind, Jones was awarded first, Donn Clendenon followed with a two-run homer, Al Weis hit one in the seventh to tie, and the Mets scored two more in the eighth to win the game and the Series.

But there were questions, most of them voiced in Baltimore, about the provenance of that baseball. Was it really the one that McNally had thrown? A nearly identical play in 1957 with Milwaukee’s Nippy Jones had helped to decide that Series. And years later an unnamed Met said that ever since, it had always been considered good planning to have a baseball in the dugout with shoe polish on it, just in case.

Today, of course, players’ shoes don’t get shined.

Hall of Fame pitcher, Hall of Fame batter, Hall of Fame manager, all involved in the fifth smartest play. But only two of them were smart in it. Reds 1, A’s nothing, one out, top of the eighth, runners on second and third, third game of the ’72 Series, and Oakland reliever Rollie Fingers struggles to a 3-2 count on Cincinnati’s legendary Johnny Bench. With great theatrics and evident anxiety, the A’s battery and manager Dick Williams agree to go ahead and throw the next pitch deliberately wide — an intentional walk.

Which is when Oakland catcher Gene Tenace jumps back behind the plate to catch the third strike that slides right past a forever-embarrassed Bench. As if to rub it in, the A’s then walked Tony Perez intentionally. For real.

Another all-time great was central to the fourth smartest play in Series history. With Mickey Mantle, you tend to think brawn, not brain, but in the seventh game of the epic 1960 Series, he was, for a moment, the smartest man in America. Mantle had just singled home a run that cut Pittsburgh’s lead over the Yankees to 9-to-8.

With one out and Gil McDougald as the tying run at third, Yogi Berra hit a ground rocket to Pirate first baseman Rocky Nelson. Nelson, having barely moved from where he was holding Mantle on, stepped on the bag to retire Berra for the second out. Mantle, on his way into no man’s land between first and second, about to be tagged hi

mself for the final out of the Series, stopped, faded slightly towards the outfield, faked his way around Nelson, got back safely to first, and took enough time to do it, that in the process, McDougald could score the tying run.

Mantle’s quick thinking and base-running alacrity would have been one of the game’s all-time greatest plays – if only, minutes later, the 9-to-9 tie he had created, had not been erased by Bill Mazeroski’s unforgettable Series-Winning Home Run to lead off the bottom of the ninth.

Like the Mantle example, the gut and not the cerebellum is associated with the third smartest play in Series history. It’s Kirk Gibson’s epic home run to win the opening game of the 1988 classic. The story is well-known to this day; Gibson, aching, knees swollen, limping, somehow creeps to the batter’s box and then takes a 3-2 pitch from another hall of fame Oakland reliever, Dennis Eckersley, and turns it into the most improbable of game-winning home runs.

But the backstory involves a Dodger special assignment scout named Mel Didier. When the count reached 3-and-2, Gibson says he stepped out of the batter’s box and could hear the scouting report on Eckersley that Didier had recited to the Dodgers, in his distinctive Mississippi accent, before the Series began. On a 3-2 count, against a left-handed power hitter, you could be absolutely certain that Eckersley would throw a backdoor slider. He always did it. And as Gibson once joked, “I was a left-handed power hitter.”

So Gibson’s home run wasn’t just mind over matter. It was also mind. And it was also Mel Didier.

The second smartest play in Series history came in perhaps the greatest seventh game in modern Series history. The Braves and Twins were locked in their remorseless battle of 1991, scoreless into the eighth inning. Veteran Lonnie Smith led off the top of the frame with a single. Just like Enos Slaughter in 1946, he then got the signal to run with the pitch, and just like Harry Walker in 1946, his teammate Terry Pendleton connected.

But something was amiss at second base. Minnesota Shortstop Greg Gagne and second baseman Chuck Knoblauch were either completing a double-play, or they had decided they were the Harlem Globetrotters playing pantomime ball. Smith, at least momentarily startled by the infielders pretending to make a play on him at second, hesitated just long enough that he could not score from first as Enos Slaughter once had. He would later claim the Twins’ infielders hadn’t fooled him at all with their phantom double play – that he was just waiting to make sure the ball wasn’t caught.

But he never scored a run, nor did the Braves. The game, and the Series, ended 1-0 Minnesota, in the 10th inning on a pinch-hit single by Gene Larkin from — appropriately enough for the subject — Columbia University.

All-stars and cup of coffee guys; fielders and hitters and baserunners and pitchers and even a scout, and stretching over a span of 102 years of Series history. And yet the smartest play is: from this past Sunday. Johnny Damon not only worked his way back from down 0-2 to a line single on the ninth pitch of the at bat against Brad Lidge, but he quickly gauged the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity with which the Phillies had seemingly presented him. Few teams employ a defensive shift towards the left side or the right when there’s a runner on base. This is largely because if there is a play to be made at second or third, the fielders who would normally handle the ball are elsewhere. With Mark Teixeira up, the Phillies had shifted their infield, right.

So Damon realized.

If he tried to steal, the throw and tag would probably be the responsibility of third baseman Pedro Feliz. Feliz is superb at third base, fine at first, has experience in both outfield corners, and even caught a game for part of an inning. But his major league games up the middle total to less than 30 and this just isn’t his job. Even if Feliz didn’t botch the throw or the tag, his meager experience in the middle infield slightly increased the odds in Damon’s favor. The question really was, what would happen immediately afterwards, if Damon stole successfully: Where would Feliz go, and who would cover third base?

Damon chose a pop-up slide so he could keep running. Feliz took the throw cleanly, but did not stop his own momentum and continued to run slightly towards the center of the diamond. And nobody covered third base. All Damon needed was daylight between himself and Feliz, and Feliz would have no chance of outrunning him to third, and nobody to throw to at third.

And all of that went through Johnny Damon’s mind, in a matter of seconds. Before anybody else could truly gauge what had happened, he had stolen two bases on one play without as much as a bad throw, let alone an error, involved. It is a play few if any have seen before, and it is unimaginable that any manager will let us ever see it again!

Thereafter, in a matter of minutes, the Yankees had turned a tie game, with them down to their last strike of the ninth inning, into a three-run rally that put them within one win of the World’s Championship. And all thanks to the Smartest Play in World Series History.

The Pete And The President And The Hall of Famer Shortage

It wasn’t the first time, and it doesn’t mean they said anything more than ‘howdy,’ but Pete Rose met with MLB President and Chief Operating Officer Bob DuPuy here in Cooperstown over the weekend.

It was also learned by the Daily News that in a meeting of the Hall of Fame’s board of directors at the Otesaga later on Saturday, two of Rose’s former teammates on the board, vice chairman Joe Morgan and Frank Robinson, also expressed their hope that Selig would see fit to reinstate Rose.

At roughly the same hour, as I first reported late Saturday night, Sparky Anderson marched into the “Safe At Home” shop as if he were going to the mound at Riverfront to pull Jack Billingham, and, tears welling in his eyes, told Rose, “You made some mistakes 20 years ago, Pete, but that shouldn’t detract from your contributions to the game.”