Category: Uncategorized

Seaver And Mathewson

On his MLB Network program Studio 42, Bob Costas tonight referenced a blog post here from 2009, and asked Tom Seaver if he was aware that I’d found a game-action photograph of Christy Mathewson from the 1911 World Series that showed Mathewson using the exact of drop-and-drive delivery Seaver brought to perfection in the early years of his career in the late ’60s.

Seaver said he’d seen the photo – I was pretty sure he had, since I’d sent a copy to him via a friend shortly after I found it in Cooperstown.

In blog years, a long time has passed since I posted the shots, so here they are again:

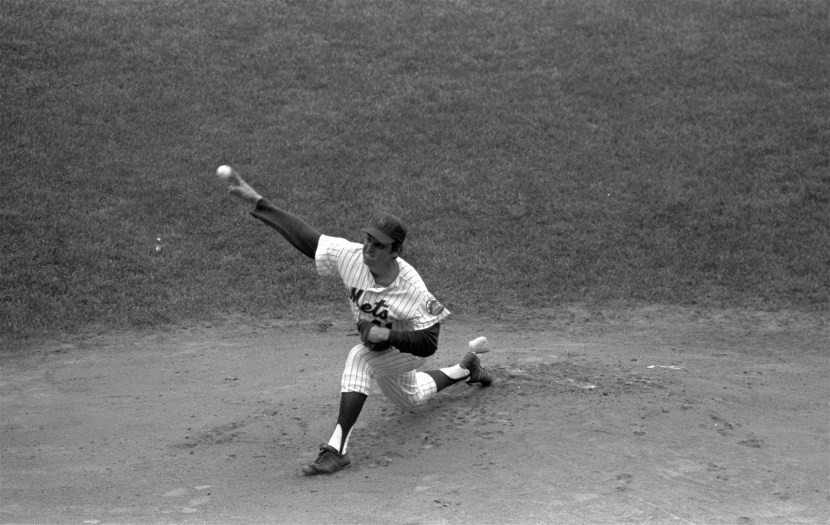

That’s Seaver – coincidentally in action against at Shea Stadium the San Francisco Giants in 1975 – showing the “drop and drive” that usually left the front of his right knee dirty. There had been a lot of anecdotal evidence that Mathewson, who retired in 1916, had used a similar delivery. But until the kind curators at the Hall photo archive let me look at their collection of glass images from the 1911 World Series, I don’t think anybody had actually seen a game-action image of Mathewson.

The resemblance, as you’ll see, is startling:

It’s the same delivery. In 1911.

Needless to say, I geeked out completely when I saw that photo. I literally thought “Why is there a picture of Tom Seaver pitching in the 1911 World Series?” After I posted the shot in August, 2009, I ran into Bob at Yankee Stadium and he had seen the post and he geeked out completely over it.

Just for the record, there are precious few game-action photos, particularly of pitchers, particularly in post-season action, from before the first World War. This was part of a series of 30 or 40 transparent glass slides, above three by five inches, that had been taken with a special camera for presentation as a slide show at the earlier movie theaters of the time. The Hall has what appears to be a complete set, and it constitutes a treasure trove for historians. You’ve heard of “Home Run” Baker? He got his name not for volume of homers, but for consecutive game-winning blasts off Mathewson and his fellow future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard in the ’11 Series. The slides include images of Baker rounding third on one of the homers.

I’m not going to say there isn’t another game-action photo of Mathewson anywhere else (and I’m not counting all the posed and/or warm-up shots that show Matty fully upright or just soft tossing). I’m just saying I’d never seen one before this image, and I don’t recall anybody reporting having seen another.

The 1911 photo series had been lost to historians because when it was donated to the hall in the mid 1960’s, the individual slides were divvied up and put, one by one, into the individual files of the players depicted. Only around 2009 was a search made for the whole set (you can imagine how long that took). This is what the Mathewson photo looked like – exactly as movie-goers would have seen it in October or November, 1911:

This is magnificent for several reasons – not the least of which is the extraordinarily low mound (which makes you appreciate Mathewson’s 373 career wins (plus five more in World Series action). But principally because that which historians thought really hadn’t become the standard for the “power pitcher” until the ’40s or ’50s, was in Mathewson’s repertoire a century ago.

Hey Hey!

Thank God.

A year too late for him to enjoy it, 30 years past the day he should’ve been selected, the Baseball Hall of Fame Veterans’ Committee has finally elected the most deserving candidate not in Cooperstown, Ron Santo.

For those who doubt, here is my statistical analysis of the five leading playing candidates:

The simplest tool for judging a player against his contemporaries is, I think, the most overlooked one – exact comparisons, from a guy’s debut season through his final year.

Awards are useful, especially as an indicator of greatness – in Ron Santo’s case, the five straight NL Gold Gloves 1964-68 pretty much confirm his defensive prowess – consider the one from 1964, when Cardinals’ third baseman and defensive hero Ken Boyer was MVP, but Santo still won the Glove.

The hardware is nice. But statistics are better.

In short, in his era, from when he came up with the Cubs in 1960 through his last year with the White Sox in 1964, Ron Santo was one of the top ten hitters in all of baseball.

Santo was fifth in RBI in his era.

Santo was ninth in Runs in his era.

Santo was tenth in Homers in his era.

Santo was tenth in Hits in his era.

There are 17 players besides Santo on these four lists of the top ten offensive producers of the 1960’s. Only four men on all four lists: Aaron, Frank Robinson, Billy Williams – and Santo. Even the three men who are only on three lists, compared to Santo’s four, are all in Cooperstown already.

Needless to say, only one other full-time Third Baseman (Brooks Robinson) shows up on any of the four lists – and he, only twice. Part-timer Killebrew is on three of them: handily ahead of Santo in one (HR), behind Santo in another (R), and just two spots and only 74 RBI ahead of him in the third.

You can’t ask more of a man than to produce those kinds of numbers against his direct contemporaries: what he did while he played, compared to what everybody else did while he played, is all that he can be judged on. But it focuses exactly where a player stood against his peers.

By the way, if you want to be more generous to Santo, and judge him from his first full year as a regular (1961) through his last year as an everyday player (1973) he looks better still: he holds at fifth in RBI, but moves up one spot each in Runs (eighth), Homers (ninth), and Hits (9th).

I had Gil Hodges second.

Again, what he did in his time tells me what I need to know. Here is a list, updated through May 5, 1963 – the date Gil Hodges played his last game in the major leagues.

All-Time MLB Home Run Leaders (RH Batters):

1. Jimmie Foxx 534

2. Willie Mays 373

3. Gil Hodges 370

4. Ralph Kiner 369

5. Joe DiMaggio 361

6. Ernie Banks 340

7. Hank Greenberg 331

8. Hank Aaron 307

8. Al Simmons 307

10. Rogers Hornsby 301

By the way, on the all-time homer list, lefties and righties both, Hodges had just been knocked out of 10th place, by Mays (373 to 370). The game changes. Still, it is extraordinary that Hodges’ home run performance measured against all his contemporaries and predecessors, is pretty much ignored.

Hodges’ career spanned 20 calendar years, but he only played regularly from 1948 to 1959. In “his” era, Hodges was second in MLB in homers (344, to Duke Snider’s 354), second in RBI (tied with Berra at 1136, behind Musial’s 1226), fourth in Runs, and seventh in Hits. Hodges is often dismissed as a “Home Park Homer Hitter.” In fact in his ten years at Ebbets Field he averaged only 4.60 homers a year more in Brooklyn than on the road. For comparison, Duke Snider, in the Hall since 1980, averaged 4.56 homers a year more in Brooklyn than on the road.

It is also of note that Hodges hit 27 or more homers in eight consecutive seasons, drove in 102 or more runs seven years in a row, and the first baseman on two World’s Champions and four more NL champs.

Haven’t even mentioned Hodges the manager (1969 Miracle Mets) nor Hodges the Man (I have never, ever talked to anyone who knew him who didn’t revere him.

Third on my list? Luis Tiant. Bill James hit the nail on the head: Luis Tiant is Catfish Hunter with poorer marketing.

Statistical doppelgangers are often either coincidental, superficial, or irrelevant because the players are of different historical eras. Not Hunter and Tiant. They pitched side-by-side in the same league for fifteen seasons, in the same division for six, and were teammates for a year. And they look like twins in a dozen key stats:

Statistic Hunter Tiant

Starts 476 489

Complete Games 181 187

Shutouts 42 49

Innings 3449.1 3486.1

Home Runs 374 346

Wins 224 229

Losses 166 172

ERA 3.26 3.30

Run Support 4.30 4.46

20-Win Seasons 5 4

Sub 3.00 ERA Seasons 5 6

‘Wins Above Team’ 20.2 20.6

That’s right: Tiant made 13 more starts, won five and lost six more games, threw seven more shutouts, and finished with an ERA 0.04 higher, than Hunter. Otherwise, they share a virtually identical statistics.

Where they deviate leaves open the question of which was the better pitcher. Tiant had 404 more strikeouts, but 150 more walks. Hunter twice led the AL in wins, which Tiant never did. Tiant twice led it in shutouts, which Hunter never did. Tiant twice led it in ERA, which Hunter did once.

Hunter’s big advantage? He made 22 ALCS and World Series starts to Tiant’s five. He was seen on the biggest stage, by fans and reporters alike, for seven of eight Octobers. Tiant had only one shot at such impact.

Beyond the Hunter comparisons, in the match-him-against his era numbers, Tiant was ninth in wins, tenth in K’s, twelfth in ERA, 1964-80 (even though in five of those seasons he did not make even 20 starts).

And there is one more remarkable and overlooked statistic. Two of Tiant’s six sub-3.00 ERA seasons were actually sub-2.00 ERA seasons. Since 1920, only 29 pitchers have had a seasonal ERA under 2.00. Koufax did it three times, and the other four did it twice: Roger Clemens, Greg Maddux, Pedro Martinez – and Tiant.

Fourth – and he’s right below Tiant – is Minnie Minoso. He’s kind of damned by the overall quality of his play: superb at a lot of contradictory things, not extraordinary at any one of them:

Who were the top five hitters during Minnie Minoso’s 13 seasons as a Major League regular, 1951-63? Keep it to the guys who averaged at least 475 at bats a year and here’s the headline: one of them was Minnie Minoso.

Highest Batting Average 1951-1963 (Minimum 6175 AB)

1. Stan Musial .319

2. Willie Mays .315

3. Richie Ashburn .309

4. Harvey Kuenn .307

5. Minnie Minoso .299

Note please, that performance included eight .300 seasons. It’s impressive stuff, but below is my favorite Minoso stat:

Highest Slugging Percentage 1951-1963 (Minimum 6175 AB)

1. Willie Mays .588

2. Stan Musial .543

3. Eddie Mathews .535

4. Minnie Minoso .461

5. Harvey Kuenn .417

The slugging number is especially astounding given that Minoso only hit 184 homers in those 13 years (28th in the era). Without being a real longball threat, he still places 8th in total bases in the span, and 9th in RBI.

Most Runs Scored, 1951-1963

1. Mickey Mantle 1381

2. Willie Mays 1258

3. Eddie Mathews 1220

4. Nellie Fox 1142

5. Minnie Minoso 1130

Seeing my point here? Pick a category, and Minoso shows up on it:

Most Stolen Bases, 1951-1963

1. Luis Aparicio 309

2. Willie Mays 248

3. Maury Wills 236

4. Minnie Minoso 205

5. Billy Bruton 193

Minoso is also fifth in hits in the era, second in doubles (behind Musial, ahead of Mays), fourth in triples, led the A.L. in hit-by-pitch ten times, won three Gold Gloves – and all this even the color line and circumstance kept him from becoming a major league regular until he was at least 28 years old.

My fifth guy out of the group is just a notch below. I love Jim Kaat and I think he belongs (as does Tommy John). I mentioned contemporaries Hunter and Tiant looking separated-at-birth. Jim Kaat and Robin Roberts are unlikely statistical twins who overlapped by only seven full seasons:

Statistic Kaat Roberts

Starts 625 609

Innings 4530.1 4688.2

Wins 283 286

Losses 237 245

Strikeouts 2461 2357

Walks 1083 902

ERA 3.45 3.41

10+ Win Season Streak 15/15 16/17

Roberts got to Cooperstown quickly because of the fact he reeled off six consecutive brilliant seasons, and despite of the fact that after the age of 28, only once did he finish more than three games above .500 in his final eleven seasons.

By contrast, Kaat won 18 as a 22-year old, slumped for a year, then starting in 1964 reeled off 17, 18, and then 25. Eight and nine years later he would produce consecutive seasons of 20 and 21 wins. As Bill James pointed out, if like Roberts, Kaat had bunched his great years instead of scattering them, he might’ve been elected in the ‘90s. As it is, he is still 31st all-time in victories — eighth all-time among lefties:

Wins, Lefthanded Pitchers:

1. Warren Spahn 363

2. Steve Carlton 329

3. Eddie Plank 326

4. Tom Glavine 305

5. Randy Johnson 303

6. Lefty Grove 300

7. Tommy John 288

8. Jim Kaat 283

9. Jamie Moyer 267

10. Eppa Rixey 266

11. Carl Hubbell 253

12. Herb Pennock 241

There are only eight active lefties with more than 100 wins, and of them, only CC Sabathia (176) is younger than 32. Kaat is also 10th in strikeouts by lefties. Kaat’s victory total has been criticized as “padded” by his five years as a reliever and spot starter. But subtract those seasons and his career won-lost improves to 261-217, he remains in the top 10 among lefties, and still has better won-losts than Ted Lyons and Eppa Rixey (and is just behind Red Faber).

Lastly, the 16 consecutive Gold Gloves are almost a cliché. We don’t stop to think that the first of them was won when Kitty was 23, and the last when he was 38 – and that the streak stretched through five presidential administrations and three expansion drafts.

Just to show my math, here are the Homer, Runs Scored, RBI, and Hit lists from ’60-’74 that back-up Santo’s greatness:

Most RBI, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Hank Aaron, 1585

2 Frank Robinson, 1412

3 Harmon Killebrew, 1405

4 Billy Williams, 1351

5 Ron Santo, 1331

6 Brooks Robinson, 1217

7 Willie Mays, 1194

8 Willie McCovey, 1190

9 Carl Yastrzemski, 1181

10 Orlando Cepeda, 1164

Most Runs Scored, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Hank Aaron, 1495

2 Frank Robinson, 1390

3 Billy Williams, 1306

4 Lou Brock, 1303

5 Willie Mays, 1285

6 Carl Yastrzemski, 1240

7 Pete Rose, 1217

8 Vada Pinson, 1177

9 Ron Santo, 1138

10 Harmon Killebrew, 1131

Most Homers, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Hank Aaron, 554

2 Harmon Killebrew, 506

3 Frank Robinson, 440

4 Willie McCovey, 422

5 Willie Mays, 410

6 Billy Williams, 392

7 Frank Howard, 380

8 Norm Cash, 373

9 Willie Stargell, 346

10 Ron Santo, 342

(Note: 11th was Orlando Cepeda, 327)

Most Hits, Majors, 1960-74:

1 Billy Williams, 2505

2 Hank Aaron, 2463

3 Brooks Robinson, 2459

4 Vada Pinson, 2455

5 Lou Brock, 2388

6 Pete Rose, 2337

7 Roberto Clemente, 2318

8 Willie Davis, 2271

9 Carl Yastrzemski, 2267

10 Ron Santo, 2254

(Note: 11th was Frank Robinson, 2220)

The Night I Realized Bobby Valentine Was Clueless

The world remembers Game Two of the 2000 World Series for one thing, and one thing alone: Roger Clemens throwing the shattered bat of Mike Piazza at, or near, Mike Piazza.

But for me, standing at the far end of the Yankee dugout, covering the Series as part of the Fox telecast, the bat event was an asterisk to the real headline. Because that was the night that I became convinced Bobby Valentine didn’t have the slightest idea what he was doing.

Lost in the Clemens saga still churning more than eleven years later, was a) the eight innings of two-hit ball he fired at the Mets (the back half of consecutive starts in which Clemens threw 17 playoff innings, gave up no runs, one hit batsman, two walks, three hits, and struck out 24 of the 58 batters he faced); b) the Mets’ incredible ninth inning rally that almost gave Clemens a no-decision; and c) Valentine’s decision during that inning, that might be the dumbest World Series managerial move since Casey Stengel completely messed up his 1960 pitching rotation.

Again, the context. Mostly because of their own baserunning lunkheadedness, plus the fact that Todd Zeile’s fly ball missed being a home run by maybe eight inches, the Mets had lost the Opener of the Subway Series the night before. Now, in Game Two, Clemens had made them look nearly as bad as he had made the Seattle Mariners look eight days before. Oh, and even though Piazza thought Clemens had thrown a bat at him, neither he, nor Valentine, nor anybody else in a Met uniform had even retaliated, let alone charged the mound or anything.

So as the Mets came up in the top of the 9th, down 6-0, they were as dead as Jacob Marley’s ghost in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Clemens had exited, stage right, to go let the adrenalin drain out of his system (along with whatever else was in there). Coming off his best major league season, Jeff Nelson was brought in to face the heart of the Mets’ order, and Joe Torre even took out David Justice for the slight defensive upgrade Clay Bellinger would represent in left.

But it did not exactly go to plan. Edgardo Alfonzo led off with a sharp single to left, and Piazza promptly got some delayed revenge by putting a Nelson pitch off the pole in left to cut it to 6-2. By this point, Torre had hastily gotten Mariano Rivera up. When Robin Ventura singled to make it three straight hits to start the ninth, Rivera was summoned, and nearly blew the game on the spot. Zeile hit another one to the wall in left, with the wind holding it up just enough to reduce it to a nice jumping Bellinger catch at the fence. But Benny Agbayani singled, and with Lenny Harris up, Jorge Posada lost a Rivera cutter and the runners moved up to second and third. Harris tapped back to Rivera who got Ventura at the plate, and the Mets were down to their final out – which was when Jay Payton walloped a massive three-run bomb off Mo and all of a sudden the Yankees’ insurmountable 6-0 lead was now a 6-5 heart-stopper, with the Mets just a baserunner away from turning over the line-up and sending up sparkplug Timo Perez with the tying run on.

Please remember this specific fact: the Mets were down to their last out, but having scored five in the ninth and rattled Mariano Rivera, they now had a chance – no matter how small a chance – to pull off a split at Yankee Stadium with three coming up at Shea. You may also remember that in midseason they had lost their other-worldly defensive shortstop Rey Ordonez, and had been forced to trade utility wizard Melvin Mora to Baltimore for Mike Bordick. Bobby V had already pinch-hit for Bordick an inning earlier with Darryl Hamilton, and went to his back-up shortstop, Kurt Abbott. If for some inexplicable reason Valentine now chose to leave Abbott in to face Rivera, he would be sending a lamb to the slaughter. Abbott had never seen Rivera or his cutter before. He was a lifetime .256 hitter with a .304 on-base percentage. After this night, only fourteen more major league at bats awaited him, and that was mainly because despite a pretty good glove and a deceptive slugging percentage, Kurt Abbott just wasn’t a major league hitter.

What happened next was explained at the time as a simple proposition. Bobby Valentine was out of shortstops, and, after all, Abbott had hit six homers during the regular season, in only 157 at bats. That none of them had been off a righthander since August 7, and that righthander was Jason Green (18 career minor league innings), and the other dingers had come off Terry Mulholland, Brian Bohanon, Jason Bere, Alan Mills, and Jose Mercedes, and that Abbott was carrying a 7-for-37 slump, seemed to have been left out of the equation.

More over, Valentine might have been out of slick shortstops, but he was hardly out of shortstops. He had at least seven defensive moves left. Joe McEwing had played four games at short for the Mets in 2000 and was still on the bench. McEwing, Matt Franco, and that night’s DH Lenny Harris had all played third during the season, and Robin Ventura could’ve easily slid over to short if the Mets had pulled off the miracle of forcing a bottom of the 9th. If that move sounded too risky, McEwing and Harris had also played second, and could have gone there with Alfonzo switching to short. Still not comfortable with pinch-hitting for Abbott? Bubba Trammell had produced a pinch two-run single the night before off Andy Pettitte. Valentine would trust Trammell enough to start him in right in the Series’ decisive game – he could have gone in to the outfield and Agbayani or Payton played first, with Todd Zeile going to third and Ventura to short. Or the same ploy could have been used with Harris, who played ten games at first for the ’00 Mets.

But, no. Bobby V knew he didn’t have any shortstops. So, having scored a remarkable five runs in the 9th – three of them off the greatest reliever the game would ever know – he sent up Kurt Abbott to try to finish the miracle. Imagine if the Mets had tied that game? Regardless of the outcome – even if the Yankees had promptly won it in the bottom of the inning thanks to an error by McEwing or Ventura at short or Bubba Trammell somewhere – the invincibility of the Yanks would have been punctured. Instead of a near-miss utterly overshadowed by the affair of Clemens And The Bat, it would have been the greatest ninth-inning comeback in World Series history.

Instead, inevitably, Kurt Abbott struck out. Looking.

The Mets lost the Series in five games, and until you just read this, it was unlikely that you remembered that “The Clemens/Piazza Game” ended with such an unlikely rally, cut short by a manager who wouldn’t pinch-hit for his good-field no-hit back-up shortstop.

But Bobby Valentine is supposed to be a great in-game tactician. Just like he’s supposed to be a no-nonsense skipper who’ll instill discipline into a flabby Red Sox team – presumably teaching them to respect authority by returning to the dugout in an embarrassing disguise after he had been ejected by the umpires. Like you have to listen to the umpires or something. And don’t tell me the Abbott decision is ancient history. As far as his major league managerial career goes, the decision to let Rivera eat Abbott alive was just 326 games ago.

Good luck, Red Sox fans.

Miami In A Vice

They have gone out and spent the money on what looks like a fabulous and distinctive new ballpark.

They have gone out and spent the money on what is an often fabulous and always distinctive new manager.

They are evidently willing to go out and spend the money (“in the range of five years, $18-$20 million a year,” per Buster Olney on ESPN) on Jose Reyes and might be able to snare Albert Pujols as well.

They even went out and spent the money on rebranding themselves as a city, not a state, and on some decent looking new uniforms (although the basic premise of the attire struck me as an adaptation of the original 1977 Toronto Blue Jays’ unis, with orange substituted for powder blue).

And I think it will all end in disaster.

As the 20th season of Marlins baseball looms, there is still almost no evidence that South Florida is a major league baseball community, or that it wants or needs big league ball. The entire dynamic could be changed by the new roofed stadium, but the certitude about that – and the willingness to wager literally hundreds of millions of dollars on that certitude – is, to me, unjustified. With the caveat that I know from sopping-wet experience that Joe Robbie/ProPlayer/Whatever Stadium was a miserable place to watch a ballgame, I still think that it’s mortifying that the Fish averaged 37,838 fans per game in their inaugural season of 1993, and 33,695 in 1994 – and never came close to that figure again.

I mean, not close. The World Champions of 1997 played before an average house of 29,190. Otherwise they have had just five seasons of more than 19,007 paid admissions per game, and four that were below 15,766 a year.

Team president David Samson thinks some improvement on the squad and the ballpark will convert a city that has for two decades been saying ‘you fill me with inertia’ will suddenly convert into producing “30 to 35,000 every single game.”

This was a city that could not support AAA baseball in the ’50s, and never again tried higher than A-ball. And I don’t buy the idea that a high-priced indoor facility in Miami proper rather than it a remarkably hard-to-get-to corner of Fort Lauderdale is now going to entice 37,000 fans away from everything else the city offers, especially at night. Pujols and Reyes would be hard to resist. Then again the Marlins fans of nine seasons ago resisted the 2003 World Champions (except for 16,290 of them each game). I’m not even sure how a $95,000,000 investment in Reyes and lord knows how much in Pujols would translate into profitability or even break-even status.

Reyes alone will not do it – ask the Mets.

As if these doubts were not enough, late last night the impeccable Clark Spencer of The Miami Herald tweeted something to make Miami fans shiver:

Source: H. Ramirez is not at all pleased at prospect of changing positions if

#Marlins sign Reyes; the two aren’t the friends many portray.

When the Reyes rumors first started, Spencer had quoted Hanley Ramirez with words that bring honor to the role of wet blanket: “I’m the shortstop right now and I consider myself a shortstop.”

One can easily see where all this will go if a) Ramirez and Reyes squabble; b) Reyes gets hurts again; c) the Marlins don’t sign enough new talent to compete in a daunting division; d) the fans don’t show up; or e) all of the above, in any order you choose. When the ’97 Marlin World Champs did not yield a new stadium, 17 of the 25 men on the World Series roster were gone by mid-season 1998 and three more by mid-season 1999.

Imagine Jose Reyes being traded in a fire sale in the middle of 2013. Or Albert Pujols.

SPEAKING OF ALBERT…

A quick thought about the new Cardinals’ manager.

I met Mike Matheny during the nightmarish 2000 NLCS when Rick Ankiel was hit by the same psychological trauma – damage to a close male relative or friend who had taught him the game – that befell Steve Blass, Chuck Knoblauch, Steve Sax, the ex-pitcher-turned-author Pat Jordan, and others. Matheny had cut up his hand opening the odd gift of a really big hunting knife, and had to turn over Cardinals’ catching to Carlos Hernandez.

Matheny was devastated, but less for himself and far more for what his absence meant to Ankiel. I don’t know that this has been reported since the time Ankiel’s problems crested (I know I put it on our Fox broadcasts of the Cards-Mets playoffs), but Matheny told me that several times during the season Ankiel had begun to spiral out of control the way he did in that heart-stopping start against New York. “But I could calm him down, I was able to stop him. Last night, watching it, I felt helpless. Worse, I felt paralyzed. I could’ve talked him out of it.”

Consider this in the later context. Ankiel was collapsing under the weight of his father – who had driven him throughout his youth and into his career – going to prison for drug-running. The problem would run Ankiel out of the majors the next year and make him an outfielder two years after that. Yet Matheny was somehow able to encourage him, reassure him, or simply bullspit him, into overcoming this set of complex psychological phenomena.

Put that into a skill set that includes good game judgement, an ability to easily relate to everybody from batboys to announcers who wouldn’t give anybody a hunter’s knife as a present in a million years, and all the other non-healing powers a manager is supposed to have, and I think it’s safe to infer Matheny will be a pretty good big league skipper.

Calvin Schiraldi: Sportsman

Frankly, MLB Network’s special 25th Anniversary commemoration of the 1986 World Series which premiered last night, could have been 7 long highlight “packages” with only my friend Bob Costas merely introducing them, and I would’ve enjoyed it.

But something unexpected happened. The players who joined Costas and Tom Verducci were Mookie Wilson of the Mets, and Bruce Hurst and Calvin Schiraldi of the Red Sox. Wilson has long been a source of reflective information on the dramatic series between the Mets and Red Sox.

Hurst proved himself erudite and frank – just as he was as a player, who was never an “easy” interview but always an insightful one. Several times he responded – reluctantly but bluntly – to particularly outlandish and unsupported comments about his teammates from 1986 Red Sox manager John McNamara, who seems to have settled in to an emeritus stage devoted to blaming the players for his erratic managing, especially during Game 6.

Costas, Wilson, Hurst, and Verducci were fine. But Schiraldi was a revelation.

He, of course, was the star-crossed Boston closer, former college teammate of Roger Clemens, and an ex-Met prospect all too familiar to his old teammates, who had struggled in the ’86 A.L. Championship Series and managed to help give back a World Series win though he retired the first two men, and had two strikes on the third, in the bottom of the final inning. It is nearly almost literally true that the last time Schiraldi was heard from publicly, he was staggering off the field at Shea Stadium, a 24-year old with his future behind him. He had seemed, at best, far from confident, and, at worst, shattered. Schiraldi would be exiled to the Cubs in 1988 and would be out of the majors in 1991.

For the first hour or so of the program Schiraldi, his once-boyish face now covered in a graying beard, wearing a strange sweatshirt and clashing with the impeccably dressed Hurst, seemed terse to the point of embarrassment. There was a kind of cringe factor growing as the game-by-game recollection of the Series moved inevitably towards his nightmare in Game 6.

But this time, Calvin Schiraldi starred.

He revealed that before Dave Henderson’s homer gave the Red Sox the lead in the top of the 10th Inning, he had been told that he had pitched to his last batter, that somebody else would throw the bottom of the presumably still-tied frame. He didn’t say it until provoked, but anybody who has ever played sports, or covered them closely, or just experienced a high-adrenaline environment, suddenly understood what happened. Having thrown two innings in the tensest environment possible, Schiraldi had been told to gear down, that he was “done.”

This is, of course, the moment during the horror film where you the viewer think the carnage is over and you’ve survived – the “placing the flowers on Carrie’s grave” moment, just before her hand shoots out of the ground to claim you. Physiologists will tell you it is not a purely psychological phenomenon. The energy and the adrenaline abate. And when it turns out Carrie is reaching out – or the manager says “Calvin, now we’ve got a two-run lead, go back out there and wrap this up” – when you reach for that energy, it’s not there – and you are on your own, and on your own against Carrie.

The show’s insight could’ve ended there with Schiraldi giving an explanation (but not an excuse) for what happened during the last 0.2 of the 2.2 innings he pitched that night. But then came something transcendent. He was asked how he felt now about the game and the series and he, presumably unknowingly, defined the true value of sports.

Schiraldi said he was obviously unhappy at the outcome of the game and the series, but he would not change the experience if it meant changing who that night made him become. That’s when Schiraldi revealed the meaning of his unusual sweatshirt. For more than a decade he’s been the baseball coach – and a teacher – at St Michael’s Catholic Academy in Austin. And the things he learned in the majors, particularly in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series, have formed the core of his value and coaching systems.

He’s used that inning to teach kids about sports – and life.

You have to hear him say it, to truly appreciate it. The MLB retrospective on the ’86 Series runs again tomorrow and Sunday afternoons at 1 PM ET. Find a way to watch, because 25 years later, Schiraldi has had an impact that merely getting the last out could never have afforded him.

NL Central 2012: Ryne Sandberg Versus The Cubs?

Fascinating that the St. Louis Cardinals have asked the Phillies for permission to interview their AAA manager Ryne Sandberg – and received it.

For the second consecutive year, Sandberg will not get the managing job with the team for which he starred. When new Cubs’ President Theo Epstein outlined his minimum standards for the next manager (experience as a major league skipper or coach) it essentially eliminated Ryno from consideration because his stints with the Phils last spring and last September do not formally rise to that level.

Yet oddly, the Cardinals are happy to at least kick the Sandberg tires. I’m not sure what it proves, but it would seem to suggest that the division of thought on Sandberg’s managerial potential may now split into those who have seen him, the Hall of Famer, willing to ride the buses of the Midwest League, and those who have actually employed him to manage their bush leaguers. Everything I heard as of March, 2010, was that the Wrigley Field job was likely to be Sandberg’s whenever Lou Piniella left. But by August, when Piniella really did leave, the Cubs had soured on Sandberg and no longer thought him viable. Off he went to the Phillies, and now they are willing to let him talk to a National League rival, and there hasn’t been a peep about Sandberg even getting a promotion to the Phillies’ major league coaching staff. Even stranger, is that before he took the Phils’ offer last winter, Sandberg interviewed for the equivalent job in the Boston system – with Theo Epstein, the same man who’s ruled him out in Chicago.

I’m reminded of Babe Ruth’s quixotic hope that the Yankees would make him their manager (they’d seen him do that with his teammate, Bob Shawkey, who had only one season managing in the minors before he got the job in New York in 1930). Perhaps the more apt comparison is Gary Carter’s campaign to get the Mets to consider him for any of their last few managerial openings.

If Sandberg doesn’t get the St. Louis job, the Cubs-Cards rivalry might still be ratcheted up by the inclusion of Terry Francona in the mix. While Epstein has said a few polite things about possible Chicago interest in Tito, the Cardinals are scheduled to interview him tomorrow. I still think St. Louis is leaning towards LaRussa’s third base coach Jose Oquendo (although I would have considered it more than “leaning” if they had brought Oquendo back into the dugout as bench coach), but it would be a fascinating dynamic if Francona got the Cardinal job and was pitted against his old cohort Epstein in Chicago.

Besides the headline names, the Cards and/or Cubs seem interested in a lot of the same men the Red Sox are interested in: Rangers’ pitching coach Mike Maddux, former Brewers’ interim skipper Dale Sveum, and Phils’ bench coach and ex-Reds and Pirates’ interim manager Pete Mackanin. If you want to follow all this on a day-to-day or even hour-to-hour basis, your best resource is the terrific MLBTradeRumors.Com site, which is a clearinghouse for every local newspaper story, every significant radio interview, and every last damn tweet on anything moving in the majors. It puts the ESPN’s and SI’s sites to shame.

So stay tuned to the prospect of Sandberg or Francona in St. Louis, and if you’re a Cub fan again tearing out your hair about Ryno, consider this Cooperstown fact. These are the Hall of Fame players who, since 1900, went on to manage “their” team: Honus Wagner (Pirates), Ty Cobb (Tigers), Walter Johnson (Senators), Tris Speaker (Indians), Nap Lajoie (Indians), Eddie Collins (White Sox), George Sisler (Browns), Rogers Hornsby (Cards and Cubs), Fred Clarke (Pirates), Jimmy Collins (Red Sox), Frank Chance (Cubs), Johnny Evers (Cubs), Joe Tinker (Cubs), Frank Frisch (Cardinals), Pie Traynor (Pirates), Mel Ott (Giants), Bill Terry (Giants), Gabby Hartnett (Cubs), Ted Lyons (White Sox), Joe Cronin (Senators and Red Sox), Lou Boudreau (Indians), Dave Bancroft (Braves), Yogi Berra (Yankees), Eddie Mathews (Braves), Red Schoendienst (Cardinals), and Tony Perez (Reds). That’s 26 guys, who managed a lot of years, yet won only 18 pennants among them — and 13 of the 18 were as player-managers and four of those were by Frank Chance. In other words, of the other 25 hometown heroes who later managed, they could collectively amass only five pennants as non-playing skippers.

The Cardinals Rally To Overcome…The Cardinals?

Was that the greatest World Series game ever played?

For games in which a team, having put itself on the precipice of elimination because of managerial and/or strategic incompetence, then stumbles all over itself in all the fundamentals for eight innings, and still manages to prevail? Yes – Game Six, Rangers-Cardinals, was the greatest World Series Game of all-time. I’ve never seen a team overcome itself like that.

But the Cardinals’ disastrous defense (and other failures) probably disqualifies it from the top five all-time Series Games, simply because it eliminates the excellence requisite to knock somebody else off the list. Mike Napoli’s pickoff of Matt Holliday was epic, and the homers of Josh Hamilton and David Freese were titanic and memorable. But history will probably judge the rest of the game’s turning points (Freese’s error, Holliday’s error, Holliday’s end of the pickoff, Darren Oliver pitching in that situation, the Rangers’ stranded runners, Nelson Cruz’s handling of the game-tying triple, the failures of both teams’ closers) pretty harshly.

For contrast, in chronological order here are five Series Games that I think exceed last night’s thriller in terms of overall grading.

1912 Game Eight: That’s right, Game Eight (there had been, in those pre-lights days at Fenway Park, a tie). The pitching matchup was merely Christy Mathewson (373 career wins) versus Hugh Bedient (rookie 20-game winner) followed in relief by Smoky Joe Wood (who won merely 37 games that year, three in the Series). Mathewson shut out the Red Sox into the seventh, and the game was still tied 1-1 in the tenth when Fred Merkle singled home Red Murray and then went to second an error. But the Giants stranded the insurance run, and in the Bottom of the 10th, as darkness descended on Fenway (the first year it was open) there unfolded the damnedest Series inning anybody would see until 1986. Pinch-hitter Clyde Engle lofted the easiest flyball imaginable to centerfielder Fred Snodgrass – who dropped it. Hall of Famer Harry Hooper immediately lofted the hardest flyball imaginable to Snodgrass, who made an almost unbelievable running catch to keep the tying run from scoring and the winning run from getting at least to second or third. Mathewson, who had in the previous 339 innings walked just 38 men, then walked the obscure Steve Yerkes. But Matty bore down to get the immortal Tris Speaker to pop up in foul territory between the plate and first, and he seemed to have gotten out of the jam. Like the fly Holliday muffed last night, the thing was in the air forever, and was clearly the play of the inward rushing first baseman Merkle. Inexplicably, Mathewson called Merkle off, shouting “Chief, Chief!” at his lumbering catcher Chief Myers. The ball dropped untouched. Witnesses said Speaker told Mathewson “that’s going to cost you the Series, Matty” and then promptly singled to bring home the tying run and put the winner at third, whence Larry Gardner ransomed it with a sacrifice fly.

1960 Game Seven: The magnificence of this game is better appreciated now that we’ve found the game film. And yes, the madness of Casey Stengel is evident: he had eventual losing pitcher Ralph Terry warming up almost continuously throughout the contest. But consider this: the Hal Smith three-run homer for Pittsburgh would’ve been one of baseball’s immortal moments, until it was trumped in the top of the 9th by the Yankee rally featuring Mickey Mantle’s seeming series-saving dive back into first base ahead of Rocky Nelson’s tag, until it was trumped in the bottom of the 9th by Mazeroski’s homer. There were 19 runs scored, 24 hits made, the lead was lost, the game re-tied, and the Series decided in a matter of the last three consecutive half-innings, and there was neither an error nor a strikeout in the entire contest.

1975 Game Six: Fisk’s homer has taken on a life of its own thanks to the famous Fenway Scoreboard Rat who caused the cameraman in there to keep his instrument trained on Fisk as he hopped down the line with his incomparable attempt to influence the flight of the ball. But consider: each team had overcome a three-run deficit just to get the game into extras, there was an impossible pinch-hit three-run homer by ex-Red Bernie Carbo against his old team, the extraordinary George Foster play to cut down Denny Doyle at the plate with the winning run in the bottom of the 9th, and Sparky Anderson managed to use eight of his nine pitchers and still nearly win the damn thing – and have enough left to still win the Series.

1986 Game Six: This is well-chronicled, so, briefly: this exceeds last night’s game because while the Cardinals twice survived two-out, last-strike scenarios in separate innings to tie the Rangers in the 9th and 10th, the Met season-saving rally began with two outs and two strikes on Gary Carter in the bottom of the 10th. The Cards had the runs already aboard in each of their rallies. The Red Sox were one wide strike zone away from none of that ever happening.

1991 Game Seven: I’ll have to admit I didn’t think this belonged on the list, but as pitching has changed to the time when finishing 11 starts in a season provides the nickname “Complete Game James” Shields, what Jack Morris did that night in the 1-0 thriller makes this a Top 5 game.

There are many other nominees — the Kirk Gibson home run game in ’88, the A’s epic rally on the Cubs in ’29, Grover Cleveland Alexander’s hungover relief job in 1926, plus all the individual achievement games like Larsen’s perfecto and the Mickey Owen dropped third strike contest — and upon reflection I might be able to make a case to knock last night’s off the Top 10. But I’m comfortable saying it will probably remain. We tend to overrate what’s just happened (a kind of temporal myopia) but then again perspective often enhances an event’s stature rather than diminishing it. Let’s just appreciate the game for what it was: heart-stopping back-and-forth World Series baseball.

Can You Hear Me Now?

As we approach 24 hours after the bizarre bullpen screw-ups that may have helped to cost the Cardinals Game 5 of the World Series, one question crystallizes out of the haze:

Seriously?

Tony LaRussa expects us to believe that his bullpen was told to get closer Jason Motte and lefty specialist Mark Rzepczynski ready, but heard only “Rzepczynski”? And following that disaster, they were again told to get Motte ready but instead thought they heard “Lance Lynn”? That the noise was so deafening and the bullpen phone so reminiscent of a string-and-juice-can, that they missed the name of the number one guy down there, and then mistook one name for another that doesn’t sound anything like it?

And most importantly, after it happened once, nobody double-checked the second time they tried to get Motte warm? No “repeat it for me! Spell it!”? Nobody down there with a sense that in a sport where the bullpen coach was blamed and fired for Bobby Thomson’s home run (“Erskine is bouncing his curve,” Clyde Sukeforth said in 1951, sending the other pitcher warming, Ralph Branca, to his Dodger doom), that screwing it up once was a fireable offense?

Even if the bullpen staff is – so to speak – off the hook in the responsibility equation: are there no monitors? Are there no coaches who don’t think Jason Motte and Lance Lynn aren’t the same guy just because they both have beards? Did we really luck out last night because Bruce Sutter didn’t find himself warming up? LaRussa and Dave Duncan never noticed the wrong pitcher was throwing? When it was shown on tv? The second time?

If all of these questions are legitimate, there should have been people fired this morning, LaRussa included. My guess is the questions are not – they’re too amateurish to be believed of the worst manager in baseball, let alone LaRussa.

And if that’s true, it raises two more and far more disturbing questions: why is LaRussa lying and what really happened?

What? You want to know about the Albert Pujols “I called the hit-and-run then chose not to swing” fantasy? Don’t get me started. Let’s just chalk that one up to extra-terrestrials.

For Heavens’ Sake: Replay!

We will never know what would’ve followed: Adrian Beltre could have popped up on the next pitch, or homered igniting a 15-run rally, or torn his ACL running out a grounder, or anything in between.

But replays, taking less than sixty seconds of real time to watch, showed conclusively that Beltre fouled a ball off his foot with one out in the ninth against Jason Motte of the Cardinals in Game One of the 2011 World Series, and, unfortunately, home plate umpire Jerry Layne missed it, and called Beltre out on a grounder to third.

There has got to be a way to make those replays useful in the process by which the toughest calls, requiring the keenest judgment and the most chances to get them right, do not become unfortunate shadows on critical games – especially ones as well played as this Series opener.

I’m not calling for mandatory replay, just what I asked for after the heartbreaking screwup by Jim Joyce that cost Armando Galarraga his perfect game in 2010: some kind of option that lets the umps utilize the staggering advances in technology that appear on the scene every year. I know that the Airport Screening Cam added tonight by Fox looked hysterically funny and even grotesquely retro – but why not utilize it? You can go with an umpire’s option to check a replay himself, or a seventh ump in the booth with a replay array, even something that requires the replay review be completed in 90 seconds, or anything you like, but let’s get the right call made, as often as possible.

And I’m sorry, I don’t buy the “human element” argument in the least. Can anybody argue that tennis has been adversely affected since the electronic systems started determining baseline calls, rather than the imperfect ruling of an official too far away to see it clearly? I honor the umpires and think them among the most noble figures in the game, and agree that nobody’s perfect nor should be expected to be. But these aren’t arguments against improved and increased replay use – they’re arguments for it. Let’s give them every tool, and stop making them feel ashamed or incompetent if they choose to use them.

If it’s at all possible, I don’t want to know what an umpire thought happened. I want to know what happened.

The Beltre play may have been decisive, or it may have been trivial. But with a batter incapable of faking a wince fast enough on a ball off his foot, plus Beltre’s not running to first, plus the likelihood that only contact with an uneven, hard surface such as the front of his shoe could have made a ball angling so oddly off the bat then move on such a straight line to the third baseman, all the factors were present for exactly the kind of call the best of umpires should love to have a second look at, and all the technology is now available to get that second look accomplished in literally seconds.

It’s time.

Cardinals To Win Series

Firstly, Rangers fans should be delighted by the headline – my 2011 predictions have been execrable (according to this blog, the series opens in Atlanta tomorrow night with the Red Sox as the visitors – or maybe it’s in Boston; maybe I got the All-Star Game wrong too).

Worse still I have a great affection for Ron Washington, his third base coach Dave Anderson, and his Game One starter C.J. Wilson. Beyond that, there is no love lost between me and Cardinals’ manager Tony LaRussa. The purist in me is offended that the regular season is so irrelevant that what it proved was the fourth best team in the National League is my pick to win the Series. And I happen to hate team catchphrases and don’t particularly care about whether the Cardinals’ flights are happy or morose.

Sigh.

Nevertheless, here are a few points that made this forecast unwelcome but necessary. You know that dreadful Cardinals’ starting rotation? Its post-season ERA is a nauseating 5.43 – and the Rangers are at 5.58. That anemic St. Louis line-up with the pitcher and the relief pitchers and a few popgun bats off the bench all hitting? It’s batting .288, getting on base at a .345 rate, slugging .448, for an OPS of .793. The awe-inspiring Texas line-up so deep with the DH that Boomstick Himself hitting way down there in the seventh? .259/.330/.434/.764. Having thus far played one more game than the Rangers, the Cardinals have outscored them 62 to 55.

Speaking of Boomstick, what if that tweak in Game 6 of the ALCS, that seeming oblique injury, merely hinders Nelson Cruz in the Series? What happens to a slugger who can’t twist his body fully without searing pain? Cruz has been fragile enough that to begin with his health is always in doubt. Worse still, there are probabilities in play here, and if your performance in the Division Series was 1-for-15 with no homers and no RBI, and then your performance in the Championship Series was 8-for-22 with six homers and 13 RBI, your performance in the World Series is much likelier to look like the first set of numbers than the second.

The DH “thing”? The Cardinals led the majors in hitting on the road, finishing third in road home runs behind only the Yankees and Red Sox. The Cardinals, thought to be comparatively weak sisters at the plate, basically led the National League in every offensive category except home runs, and struck out the fewest times in the NL. To be fair, Texas struck out even less – 48 times less – but without pitchers hitting the stat is slightly deceptive for comparison purposes. Cardinals’ pitchers struck out 111 times as batters during 2011, meaning their eight position players (and pinch-hitters and DHs) only struck out 867 times in total.

Then there is the little matter of the efficacy of starting three lefthanders against the Cardinals (in point of fact, if all three games scheduled for Arlington are played, St. Louis would face the three southpaws in a row). I appreciate the fact that the Cardinals did better against righties than any other NL team (and overall sit behind only Texas throughout the sport), and I’m aware that the key to beating the Cards this year has been to make Lance Berkman bat from the right side, where he is useful but not a force. But it still strikes me as inherently dangerous to offer Albert Pujols, Matt Holliday, a blossoming David Freese, and Allen Craig the opportunity to face the likes of Wilson, Holland, and Harrison. To me the play is to bag one of the lesser two and opt for Alexi Ogando, rather than waiting for Holland to blow up again and then going and getting Ogando. Against lefties in the post-season the Cardinals battered Cliff Lee, were bewildered by Randy Wolf, and held their own in a loss to Cole Hamels.

The bullpens have both been superb – the Cardinals’ particularly – and the fact that neither team had to go to a seventh game in the LCS means both sets of relievers are likely to be fresh. If there is one intangible in Texas’s favor in this series, it’s that they’ve faced Octavio Dotel and Marc Rzepczynski this year, with some success. In fact they hung a loss Rzepczynski as recently as July 23, even though the Eyechart Man was effective against David Murphy (0-2) and Mitch Moreland (0-1) in four appearances. As images of Rzepczynski nearly getting Pujols killed Saturday night dance in the heads of Cardinals fans, it is trivially noteworthy to remember that his loss in Arlington nearly three months ago resulted from his own throwing error on a Moreland sacrifice.

So if you want to get an exotic wager in on the weirdest thing that could happen in the World Series, it would be Rzepczynski blowing an inning, or a lead, or a game, by picking up a bunt and running face first into Pujols for a solid E-1 and possible concussion.

Of course, just picking the Cardinals is an exotic enough wager.