Tagged: Casey Stengel

The Cardinals Rally To Overcome…The Cardinals?

Was that the greatest World Series game ever played?

For games in which a team, having put itself on the precipice of elimination because of managerial and/or strategic incompetence, then stumbles all over itself in all the fundamentals for eight innings, and still manages to prevail? Yes – Game Six, Rangers-Cardinals, was the greatest World Series Game of all-time. I’ve never seen a team overcome itself like that.

But the Cardinals’ disastrous defense (and other failures) probably disqualifies it from the top five all-time Series Games, simply because it eliminates the excellence requisite to knock somebody else off the list. Mike Napoli’s pickoff of Matt Holliday was epic, and the homers of Josh Hamilton and David Freese were titanic and memorable. But history will probably judge the rest of the game’s turning points (Freese’s error, Holliday’s error, Holliday’s end of the pickoff, Darren Oliver pitching in that situation, the Rangers’ stranded runners, Nelson Cruz’s handling of the game-tying triple, the failures of both teams’ closers) pretty harshly.

For contrast, in chronological order here are five Series Games that I think exceed last night’s thriller in terms of overall grading.

1912 Game Eight: That’s right, Game Eight (there had been, in those pre-lights days at Fenway Park, a tie). The pitching matchup was merely Christy Mathewson (373 career wins) versus Hugh Bedient (rookie 20-game winner) followed in relief by Smoky Joe Wood (who won merely 37 games that year, three in the Series). Mathewson shut out the Red Sox into the seventh, and the game was still tied 1-1 in the tenth when Fred Merkle singled home Red Murray and then went to second an error. But the Giants stranded the insurance run, and in the Bottom of the 10th, as darkness descended on Fenway (the first year it was open) there unfolded the damnedest Series inning anybody would see until 1986. Pinch-hitter Clyde Engle lofted the easiest flyball imaginable to centerfielder Fred Snodgrass – who dropped it. Hall of Famer Harry Hooper immediately lofted the hardest flyball imaginable to Snodgrass, who made an almost unbelievable running catch to keep the tying run from scoring and the winning run from getting at least to second or third. Mathewson, who had in the previous 339 innings walked just 38 men, then walked the obscure Steve Yerkes. But Matty bore down to get the immortal Tris Speaker to pop up in foul territory between the plate and first, and he seemed to have gotten out of the jam. Like the fly Holliday muffed last night, the thing was in the air forever, and was clearly the play of the inward rushing first baseman Merkle. Inexplicably, Mathewson called Merkle off, shouting “Chief, Chief!” at his lumbering catcher Chief Myers. The ball dropped untouched. Witnesses said Speaker told Mathewson “that’s going to cost you the Series, Matty” and then promptly singled to bring home the tying run and put the winner at third, whence Larry Gardner ransomed it with a sacrifice fly.

1960 Game Seven: The magnificence of this game is better appreciated now that we’ve found the game film. And yes, the madness of Casey Stengel is evident: he had eventual losing pitcher Ralph Terry warming up almost continuously throughout the contest. But consider this: the Hal Smith three-run homer for Pittsburgh would’ve been one of baseball’s immortal moments, until it was trumped in the top of the 9th by the Yankee rally featuring Mickey Mantle’s seeming series-saving dive back into first base ahead of Rocky Nelson’s tag, until it was trumped in the bottom of the 9th by Mazeroski’s homer. There were 19 runs scored, 24 hits made, the lead was lost, the game re-tied, and the Series decided in a matter of the last three consecutive half-innings, and there was neither an error nor a strikeout in the entire contest.

1975 Game Six: Fisk’s homer has taken on a life of its own thanks to the famous Fenway Scoreboard Rat who caused the cameraman in there to keep his instrument trained on Fisk as he hopped down the line with his incomparable attempt to influence the flight of the ball. But consider: each team had overcome a three-run deficit just to get the game into extras, there was an impossible pinch-hit three-run homer by ex-Red Bernie Carbo against his old team, the extraordinary George Foster play to cut down Denny Doyle at the plate with the winning run in the bottom of the 9th, and Sparky Anderson managed to use eight of his nine pitchers and still nearly win the damn thing – and have enough left to still win the Series.

1986 Game Six: This is well-chronicled, so, briefly: this exceeds last night’s game because while the Cardinals twice survived two-out, last-strike scenarios in separate innings to tie the Rangers in the 9th and 10th, the Met season-saving rally began with two outs and two strikes on Gary Carter in the bottom of the 10th. The Cards had the runs already aboard in each of their rallies. The Red Sox were one wide strike zone away from none of that ever happening.

1991 Game Seven: I’ll have to admit I didn’t think this belonged on the list, but as pitching has changed to the time when finishing 11 starts in a season provides the nickname “Complete Game James” Shields, what Jack Morris did that night in the 1-0 thriller makes this a Top 5 game.

There are many other nominees — the Kirk Gibson home run game in ’88, the A’s epic rally on the Cubs in ’29, Grover Cleveland Alexander’s hungover relief job in 1926, plus all the individual achievement games like Larsen’s perfecto and the Mickey Owen dropped third strike contest — and upon reflection I might be able to make a case to knock last night’s off the Top 10. But I’m comfortable saying it will probably remain. We tend to overrate what’s just happened (a kind of temporal myopia) but then again perspective often enhances an event’s stature rather than diminishing it. Let’s just appreciate the game for what it was: heart-stopping back-and-forth World Series baseball.

Pitchers Warmed Up…Where?

Veteran baseball people were barely done scratching their heads at the sudden rush to declare Opening Day starters in February – to tentatively hint at a violation of the mix of superstition and inchoate fear they call “tradition” – when injury claimed a pitcher who was merely scheduled to start the Spring Training opener.

Adam Wainwright may not only miss pitching in this Cardinals’ camp; he may not experience Spring Training again until 2013. The ligament damage near his elbow is profound enough to shelve him until sometime during the ’12 season, and could have as big an impact on a team and a franchise as any such injury in recent history, maybe since Sandy Koufax’s retirement put the Dodgers into a funk that lasted eight seasons. Not only does it neuter a Cardinal team that fell behind Cincinnati last season, and Milwaukee last off-season, but it could even impact the team’s ability and willingness to commit huge money to Albert Pujols next off-season.

The larger question pertains to the feeling that these injuries happen more now than they did ‘in the past.’ This question itself has been around long enough to become a baseball tradition of sorts. Surely they don’t happen that much more often. Koufax quit before his fragile elbow might have snapped like a twig. Don Drysdale retired in mid-season just three years later. 1958 Cy Young winner Bob Turley blew up a year later. And countless careers ended as did Mel Stottlemyre’s: with a run in, a man on, and nobody out in the top of the 4th at Shea Stadium on June 11, 1974 (he’d come back for two more innings two months later, then pitch a little the following March, but his rotator cuff was gone).

But the reality is that more pitchers today are warned in advance of these potentially career-ending events. Wainwright isn’t necessarily a victim of some awful turn in pitching mechanics, but rather the beneficiary of greater understanding of their impact, and far greater options in terms of repair. Given how little pain he reported, if this ligament issue had sprung up in Spring Training 1911, he would’ve tried to pitch through the pain, because contrary to today, his livelihood depended on not resting an injury. He might’ve struggled to an 11-12 record this year, had constant pain, started ’12 0-3 and wild as anything, and gone to the minors, never to be heard from again.

Still there is the nagging suspicion that we are doing something to our pitchers that makes Complete Games chimerical dreams, and the four-man rotation and the nine-man staff as comically antiquated as the horse-and-buggy. Denny McLain spent August 29, 1966 – as The Sporting News merrily noted – “struggling to a 6-3 decision over the Orioles…McLain allowed eight hits, walked nine, and struck out 11.” He threw 229 pitches. Two seasons later McLain started 41 games (and won 31 of them). Three years later, he started 41 games (and won 24 of them). The other stat – 51 Complete Games in the two seasons – was not repeated not because of arm problems but due to a suspension for associating with gamblers (the arm problems came a year later).

We know pitchers no longer “save” anything for the 9th Inning (that went out with Jack Morris; it used to be true of the top 25 starters in each league), and that without a fastball in the high 80’s you will now never get signed, and unless something else about you is spectacular, even that will only get you a career serving as the Washington Generals to the Harlem Globetrotter Prospects in the minors.

But I have long wondered if one tiny change of rituals might have contributed just enough to the wear-and-tear on pitchers to have actually made a difference. The ritual is represented by the smiling fellow at the left, Galen Cisco, the long-time pitching coach who hurled for the Red Sox, Mets, and Royals from ’61 through ’69.

But I have long wondered if one tiny change of rituals might have contributed just enough to the wear-and-tear on pitchers to have actually made a difference. The ritual is represented by the smiling fellow at the left, Galen Cisco, the long-time pitching coach who hurled for the Red Sox, Mets, and Royals from ’61 through ’69.

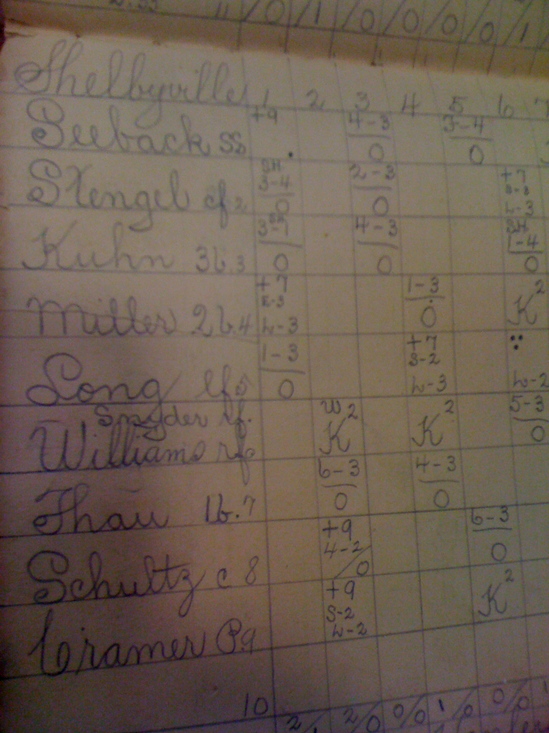

On August 7th, 1964, Al Jackson of the Mets gave up three runs in the first inning. The next day it was two off Cisco; a day later, one off Tracy Stallard in the first. Then came two consecutive scoreless firsts, followed by a doubleheader in which Jackson surrendered one in the first of the opener and Stallard three in the first of the nightcap. Finally on August 15th came the deluge: six first inning runs off Jack Fisher. So as they sent Cisco out to start on August 16, manager Casey Stengel and coach Mel Harder did something radical.

Cisco promptly retired Tony Gonzalez, Dick Allen, and Johnny Callison, and an ecstatic Lindsey Nelson told his Mets radio audience: “Galen Cisco, who warmed up in the bullpen, where there is a mound, in an effort to be better prepared in the top half of the first inning, gets them out in order!”

Your inference is correct. In 1964, starting pitchers did not automatically warm up in the bullpen. When I first heard this old tape I was flashed back to the summer of my tenth year, and the newfound joy of seeing a doubleheader from behind the screen at Yankee Stadium. There, in my mind’s eye, are the starters in the nightcap, Stan Bahnsen of the Yankees and Joe Coleman of the Washington Senators, warming up, on either side of the plate, throwing to catchers whose butts are pressed up against the backstop.

Years ago, Cisco, by then pitching coach of the Phils, insisted to me that he had been no trailblazer, and he had warmed up in the bullpen before August 16, 1964, and that other pitchers had, too. But I know I saw Elrod Hendricks, wearing a mask, warming somebody up long before a game at the new Yankee Stadium, dating it no later than 1976. I was on the field and I had to walk all the way around he and his pitcher. I photographed Goose Gossage throwing, and throwing hard, to somebody in front of the visitors’ dugout in New York that same summer, and it was four years later that I got trapped in a space beyond the third base camera well at Shea Stadium because Scott Sanderson and another Expo twirler were airing it out, pre-game.

Somewhere in the twenty year span of the ’60s and ’70s, the idea that relievers warmed up in the bullpen because they had to “get ready fast,” but starters should warm up from a rubber just on the foul side of either the first or third base foul line, changed into what we see today: everybody warms up in the pen, before, during, or after a game, and again between starts.

Ever had a workout with a trainer? Or just a well-led class at a gym? From yoga to weights, if the guy or gal wants to punish you, they’ll have you do whatever you’re doing, on an uneven surface. Incline or decline, it’s tougher if you’re not on flat ground. To really burn you, they’ll even have you stride downwards or upwards as you lift that weight or try to balance on one foot.

This is not offered as an explanation for all of the woes of the modern pitcher. But a warm-up pitch thrown from a mound is a distant cousin of a pitch to Pujols with two on and nobody out in the 5th. A warm-up pitch from the flat ground is a distant cousin of…playing catch. In short, if Denny McLain had 229 pitches in him on one day in August, 1966, he didn’t use up 20 or 30 or 50 of them before they played the Anthem.

Maybe that’s why Casey Coleman of the Cubs is really one percent likelier to get catastrophically hurt (and 90% likelier to not throw a Complete Game) than his dad Joe did that night in the Bronx (WP: Coleman, 7-7. CG. 11 K, 2 BB, 2 H, Time: 2:37).

Just a thought.

A Modest (Moot) Proposal

So Adrian Beltre is going to cost the Texas Rangers $16 million a year for six years, and Derek Jeter is going to cost the New York Yankees $17 million a year for three years (maybe more).

Joe Torre Is Not An Un-Person

“You remember some of those despotic leaders in World War II, primarily in Russia and Germany, where they used to take those pictures that they had taken of former generals who were no longer alive, they had shot ’em. They would airbrush the pictures, and airbrushed the generals out of the pictures. In a sense, that’s what the Yankees have done with Joe Torre. They have airbrushed his legacy. I mean, there’s no sign of Joe Torre at the Stadium. And that’s ridiculous. I don’t understand it.”

McCarver has apologized for the imagery (you hate the Yankees? Fine. The “rooting for the Yankees was like rooting for U.S. Steel” is stern enough, we don’t have to bring Hitler and Stalin into this). But he sticks to the contention that the Yankees have “airbrushed” Torre from their history and should have retired his number by now.

Let’s address the number first. Torre has been gone for only two-and-a-half seasons. Nobody else has been assigned his old uniform number 6. In examining the retirements, the Yankees have shelved fifteen numbers representing sixteen players (both Yogi Berra and Bill Dickey wore number 8). Mariano Rivera’s 42 will be automatically retired upon his departure from the Bronx, in keeping with the baseball-wide retirement of the number to honor Jackie Robinson in 1997 (and doubtless Rivera will get his own ceremony since he’s clearly earned it).

Fourteen of the sixteen honorees were, at the time of their uniform retirements, either still working for the Yankees, out of baseball, or deceased. When Casey Stengel’s number 37 was put away for good in 1970, it had been a decade since he had last managed the Yankees and half of one since he had last managed the Mets. He still had a largely ceremonial vice presidency with the Mets and still suited up for short stints during spring training. Berra was managing the Mets when the number he and Dickey was retired in 1972. By then Yogi, too, had been away from the Yankees for a long time – eight years.

There is some logic in delaying, especially for individuals still living. I found what is in retrospect a hilarious blog post from September, 2007, declaring that the Yankees would “surely” be one of three teams to retire the number of a veteran player: Roger Clemens. Yeah, and don’t call me Surely.

Clearly the Yankees are honoring Torre by not handing his old number to anybody else. But has he been under-represented in terms of imagery at the new Stadium? McCarver acknowledged he saw some photos of his old friend in the park and did had not meant for the “airbrushed” imagery to be taken literally.

Turns out there are 21 photos of Torre on display at the new Stadium. One of them is just Joe and Steinbrenner, giant-sized, at one of the park’s street entrances. I saw a couple of others of note tonight in the Bronx, in my first visit since McCarver’s remarks. This would be the entrance to Suite Number 6 down the first base line. The motif is pretty straight forward for each suite – a series of photos of the Yankees who wore each number, even a list of them in the alcove just outside the door. And the pride of place in terms of photography goes to the odd image you see at the left. In fact, let’s get a little closer and see just who that particular Number 6 happens to be:

I’m not sure who that is with him, but that would be Joe Torre on the left. And the idea that he is somehow being dissed by being shown back-to-the-camera denies the purpose of the photograph: each suite emphasizes the Yankees who have worn that number.

Off point, no, I do not believe there is a Suite 91 featuring nothing but photos of Alfredo Aceves.

Now, the image above is a small, untitled photo, correct? Doesn’t emphasize Torre’s vast contributions to the remarkable streak of four titles in five years? Try this, from the main concourse of the stadium, behind the ground level seats, down the left field line.

Prime location? Two beer stands and a men’s room?

Each Yankee championship team is remembered with a three-photo display. It starts with 1923 in the farthest corner of Right Field and then moves chronologically back towards the plate and out to Left. And who are the guys in the farthest right panel?

That’s right: the late George Steinbrenner, Rudolf Giuliani, and dressed for a very cold parade day from 2000, Joe Torre.

I’ll repeat myself here. I’m a fan and friend of Tim McCarver’s, and Joe Torre is my oldest baseball friend. I’ve even worked with them both. And I know the Yankees could have done better by Joe, and his exit was unceremonious and poorly-handled by the club. I would also argue that the Yankees are the most self-important, overly-serious franchise in overtly pro sports (I can think of about 27 college programs that would at least give them a run for their money).

But Timmy was just wrong, in style and in substance. Neither literally nor figuratively have the Yankees excised, erased, airbrushed nor Memory-Hole’d Joe Torre. Doubtless the day will come soon, perhaps even while he’s still managing elsewhere, that they will formally retire the number and give him the big ceremony he deserves. To see a conspiracy in the fact that the day has yet to come is, at best, to overreact.

Swinging At The Future; Whiffing At The Past

Two books to address today, one brand new, one kinda.

But I can’t trust him. The book is riddled with historical mistakes, most of them seemingly trivial, some of them hilarious. One of them is particularly embarrassing. Vaccaro writes of the Giants’ second year in their gigantic stadium, the Polo Grounds:

…to left field, the official measurement was 277 feet, but the second deck extended about twenty feet over the lower grandstand, meaning if you could get a little air under the ball you could get yourself a tidy 250-foot home run…

his glove, is the left field foul line.

There is a lot of historical tone-deafness – particularly distressing considering Mr. Vaccaro often covers the Yankees. He recounts a conversation among McGraw and New York sportswriters about the Giants taking in the American League New York Highlanders as tenants at the Polo Grounds for the 1913 season. Vaccaro quotes the famed Damon Runyon telling McGraw that his paper’s headline writers have a new name intended for the team: The Yankees. McGraw is quoted as wondering if it will catch on in 1913. Even if the mistake originates elsewhere, it should’ve rung untrue to Vaccaro: The name “Yankees” had been used on the baseball cards as early as 1911, and on a team picture issued by one of the New York papers in 1907. If McGraw and Runyon hadn’t heard the name “Yankees” by the time of the 1912 World Series, they’d both had undiagnosed hearing problems for five years.

as 1911, and on a team picture issued by one of the New York papers in 1907. If McGraw and Runyon hadn’t heard the name “Yankees” by the time of the 1912 World Series, they’d both had undiagnosed hearing problems for five years.

“I took it over my left shoulder and with my bare hand although I clapped my glove on it right away and hung on like a bulldog in a tramp,” Evans would soon tell the mountain of reporters…

…become a part owner of the American Association, a top Triple-A-level minor league…”

Post professional career

In 1929 Speaker replaced Walter Johnson as the manager of the Newark Bears of the International League, a post he held for two years. He became a part owner of the American Association. The announcement of Speaker’s election to the Baseball Hall of Fame was made in January, 1937.

How sad.

The Pete And The President And The Hall of Famer Shortage

It wasn’t the first time, and it doesn’t mean they said anything more than ‘howdy,’ but Pete Rose met with MLB President and Chief Operating Officer Bob DuPuy here in Cooperstown over the weekend.

It was also learned by the Daily News that in a meeting of the Hall of Fame’s board of directors at the Otesaga later on Saturday, two of Rose’s former teammates on the board, vice chairman Joe Morgan and Frank Robinson, also expressed their hope that Selig would see fit to reinstate Rose.

At roughly the same hour, as I first reported late Saturday night, Sparky Anderson marched into the “Safe At Home” shop as if he were going to the mound at Riverfront to pull Jack Billingham, and, tears welling in his eyes, told Rose, “You made some mistakes 20 years ago, Pete, but that shouldn’t detract from your contributions to the game.”

Meet Wilbur Huckle. Again.

Last month I introduced you to Wilbur Huckle, the latest apparent inductee into a very unfortunate, star-crossed club: guys who were on big league rosters, eligible to play in big league games – and never did.

HUCKLE CALLED UP TO VARSITY�

San Antonio’s Wilbur Huckle, who was named the all-star shortstop in the Class A Carolina League, has joined Casey Stengel’s Mets.

Huckle flew from Raleigh to New York Tuesday to join the parent club. “He didn’t know whether the Mets planned to play him any, or whether they just wanted him to work out with the club a few days,” his father, Allen Huckle said Wednesday. “We’ve been hoping to see his name in a box score.”

Wow. That last line – given that they never would, is particularly poignant.