Tagged: Keith Olbermann

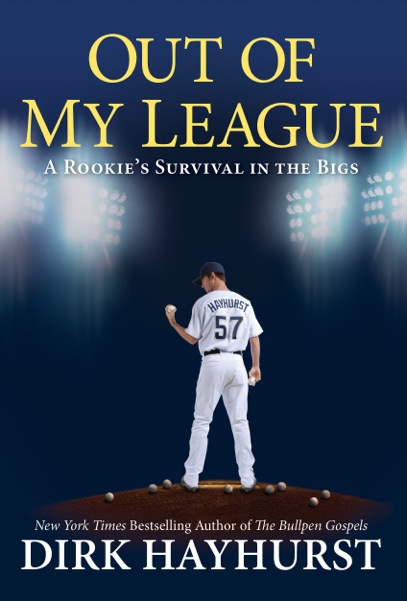

Dirk Hayhurst Returns

The entire roster is very small and I’m not even confident we have one guy for every position (although we have the beginnings of a pitching staff), but there is no question that if they ever open a Players/Authors Hall of Fame next to the larger one in Cooperstown, Dirk Hayhurst will be a first ballot electee.

And as of today he has two titles to put on his plaque. Out Of My League is now officially published and available in all formats, and without a prescription.

The Bullpen Gospels, his startling and unexpected 2010 debut as an author, told the gritty yet funny and redeeming story of a ballplayer’s sudden realizations that a dream career can still turn into a desperately unpleasant job, and that all but about six guys in his minor league were merely there to provide game-like practice for the actual prospects. It became a New York Times best-seller. If you want my detailed unabashed joy at reading the best baseball book since Ball Four, here is my original post from December, 2009.

In Out Of My League Dirk’s journey takes him to the majors with the Padres in 2008, and while the experience does not have quite the range of emotions as his first book (that would have required him to produce two baseball versions of Poe’s The Pit And The Pendulum) there are enough laughs and terrors to keep any baseball fan – or just any person – riveted.

In Out Of My League Dirk’s journey takes him to the majors with the Padres in 2008, and while the experience does not have quite the range of emotions as his first book (that would have required him to produce two baseball versions of Poe’s The Pit And The Pendulum) there are enough laughs and terrors to keep any baseball fan – or just any person – riveted.

Without scooping his story and telling it as my own, Hayhurst goes – in the span of one baseball season and one book – from moments of absolutely certainty that his career will end with nothing more achieved than the faint afterglow of a Texas League Championship, to being the starting pitcher against the San Francisco Giants. The same kind of disillusionment that made The Bullpen Gospels a universal story of handling the sour taste of reality – and one that you also discover to your shock, not everybody around you is bright enough to perceive – continues in the new book.

That this unhappy surprise comes at the major league level makes Out Of My League a touch more heretical, because it dents the fiction that The Bigs are Perfection With Whipped Cream On Top. Just because you’d give your right arm to pitch a game in the majors does not mean that’s a greater sacrifice than giving 20 years of your life for exactly that same singular opportunity. When you think of it in those terms – and Hayhurst forces you to – it suddenly seems less like the childhood dream of fame and success, and more like the scenario in which you get that bicycle you desperately wanted for Christmas, and are promptly directed to spend nearly all of your youth learning how to ride it, with the reward being your opportunity to guide it across a tightrope stretched across the two rims of a bottomless pit.

And still it’s a fun read. Plus, it will explain the hesitation of most modern pitchers. Once you read Out Of My League you’ll understand exactly where that uncertainty comes from: The pitcher staring back over his own shoulder is not always just checking a baserunner’s lead.

Baseball Prospectus 2012

Got it first Sunday at a chain bookstore here and have not dived fully in, but the predictions based on Statistical Reduction and a dozen other complicated formulae cascade out upon you from every page and it’s worth mentioning a few even before anybody’s done a thorough vetting of what they’ve got.

The most poignant of them, perhaps, are the minimalist predictions for the Yankees’ only offensive addition (“his dense hasn’t been good in a decade, and his bat is barely good enough to fill a DH role”) compared to the man the franchise downgraded, degraded, and then forced into retirement:

Player PA 2B 3B HR RBI AVG/OBP/SLG WARP

Raul Ibanez 552 28 3 17 65 .251/.311./.416 1.5

Jorge Posada 376 18 0 13 45 .260/.350/.440 2.1

The predictions were done, obviously, before Ibanez signed with the Yankees and do not account for their intention to sit him against lefthanders. If that brings Ibanez’s predicted Plate Appearances down the 32 percent or so to where the Posada predicted Plate Appearances are, the BP forecast for Ibanez translates to 19 doubles, 2 triples, and 44 RBI.

In short, the stats – and remember this is the predictive formula that got Evan Longoria’s rookie season virtually exactly correct, even though it had nothing but college and minor league data to work with – suggest Jorge Posada would’ve had a better year than Raul Ibanez will have. This underscores a point that has become clearer and clearer to me since the Montero-Pineda trade: Brian Cashman and the Yankees are approaching 2012 in exactly the opposite way they should be. They are not flush with hitting and weak with starting. Their offense is, in fact, getting dangerously old, and the only immediate productivity from their farm system was likely to be more starting pitching (the traded Hector Noesi, plus Manuel Banuelos and Dellin Betances). They did not have a hitter to trade, least of all one that Cashman compared to Miguel Cabrera.

I’ll go into the Yankees’ age problem in another post but the Alex Rodriguez prediction is appropriate here:

Player PA 2B 3B HR RBI AVG/OBP/SLG WARP

Alex Rodriguez 437 18 0 24 66 .279/.377/.525 4.3

Ack.

BP has long been known as a deflator of the balloons of hope. It sees Mike Trout getting just 250 ups this year, with a 4-24-.254/.317/.369 line. Bryce Harper gets the same number of plate appearances, and just 7-26-.239/.304/.383. The rookies it likes best include an unusually large lot of catchers: Jesus Montero (2.7 WARP), Robinson Chirinos (2.5), Ryan Lavarnway (2.3; I agree; Boston hopes this year may rest on whether or not anybody on the “New Sox” has the vision to see it); James Darnell (2.1) and Devin Mesoraco (2.1). The likelies to crash (in terms of WARP falloff) are Jose Bautista, Jacoby Ellsbury, Alex Gordon, Matt Kemp, Alex Avila, and Jeff Francoeur – but even with that it still sees Bautista at 9th in that category in the AL and Kemp tied for 7th in the NL.

What it says about the big Pujols move, and the other transactions, I leave to the hard-working editors and publishers. I’ve stolen enough of their thunder.

As to an evaluation of the book itself, there is a format change. In past years, players were grouped by the teams they were with in the preceding year. In this edition, all those who have moved before the publishing deadline have been put in the sections of their new teams – which sounds great, except when you go looking for Pujols and Fielder you’ll find the former with the Angels and the latter with the Brewers instead of the Tigers. It’s a nice try but ultimately not helpful.

And in what is either a booming typo or a bizarre redefinition, the very last leader board in the book – Rookie Pitchers’ WARP – seems to list last year’s rookie pitchers. Unless I’m missing something, Pineda, Hellickson, Ogando, Kimbrel, Sale, et al, don’t get a second bite at the kiddo apple.

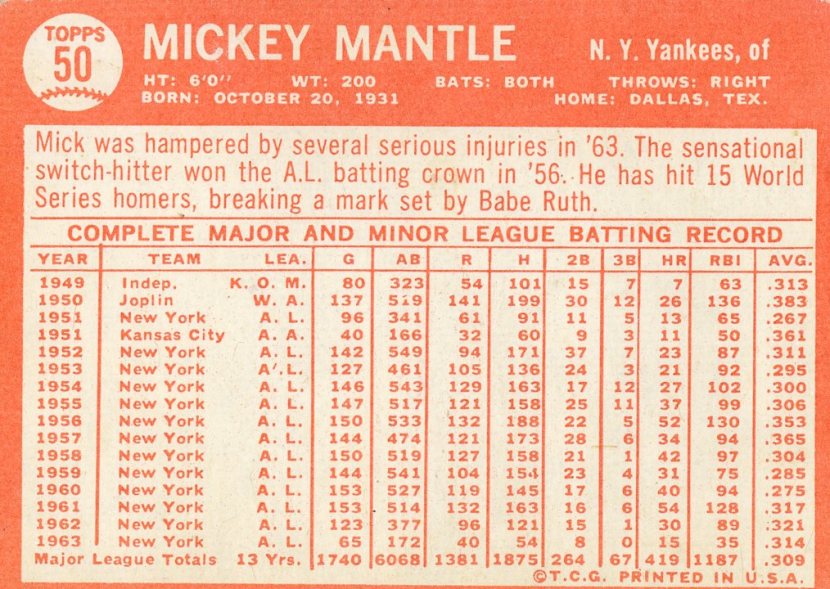

Sampling Baseball Cards Of The Past

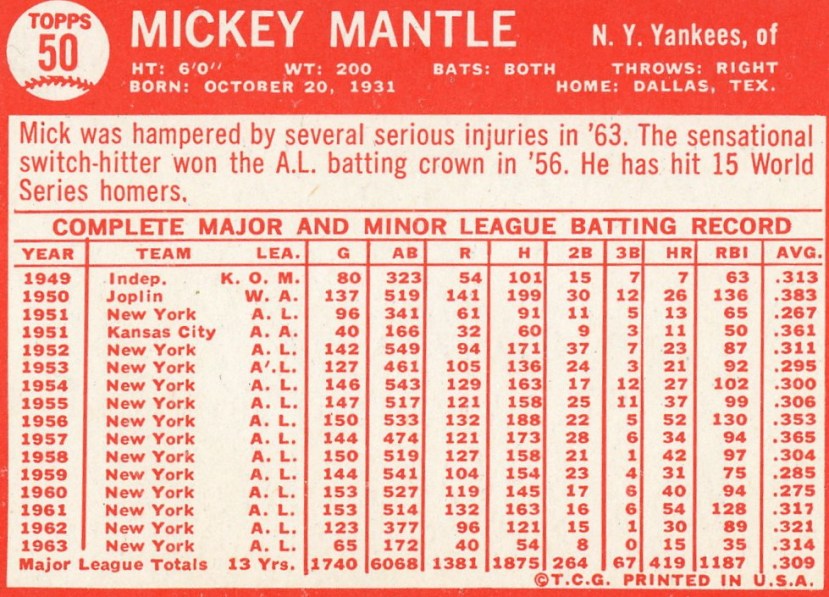

OK, look carefully. This is the back of the 1964 Topps baseball card of Mickey Mantle: Now, take a look at the back of this 1964 Topps baseball card of Mickey Mantle:

Now, take a look at the back of this 1964 Topps baseball card of Mickey Mantle:

See the difference? I mean, besides the fact that the second card is printed in a vibrant red and the first one is distinctly orange.

It’s in the biography. The first card mentions Mantle’s (then) 15 World Series homers, “breaking a mark set by Babe Ruth.” The second one stops at the reference to the homers. No Ruth. I discovered this literally Sunday afternoon – and I’ve never heard any mention of it before. But if you’re a Mantle collector don’t go nuts and decide you have to go and find this suddenly priceless variation card.

Because it not only isn’t a variation, it’s not even a real card. From 1952 through 1967, Topps produced “Salesman’s Samples” with which to excite candy jobbers and retailers about the upcoming year’s baseball cards.

Because it not only isn’t a variation, it’s not even a real card. From 1952 through 1967, Topps produced “Salesman’s Samples” with which to excite candy jobbers and retailers about the upcoming year’s baseball cards.

The one shown here on the left is from 1964, and on the front there are three cards from Topps’ 1964 1st Series (Carl Willey and Bob Friend are the “big” names). On the back, this blood-red pitch for the ’64 set and the special “bonus” – the first set of baseball “coins” Topps ever made.

And then there at the bottom is the variant Mantle card, without the reference to Babe Ruth. Trust me, if two different versions of the ’64 Mantle had been included in the actual set, the scarcer one would cost a fortune.

These Salesman’s Samples are very scarce, too, but it wasn’t until the Mantle biography change jumped out at me did I decide to inspect the others to see if the Mantle change was unique.

It wasn’t. While it doesn’t look like any of the card fronts have been changed, not so for the backs.

Until 1957, only card fronts appeared on the Samples, so there were no backs to check, but sure enough, there’s a change that very first year.

Until 1957, only card fronts appeared on the Samples, so there were no backs to check, but sure enough, there’s a change that very first year.

As shown above, by 1964 Topps had long since realized that you needed some star power, even on the Salesman’s Samples and even just on the back.

After his 61-homer season in ’61, a version of Roger Maris’s card number one is on the back of the 1962 Sample. There’s Mantle in ’64, and the ’66 has a picture of a Sandy Koufax insert on the back.

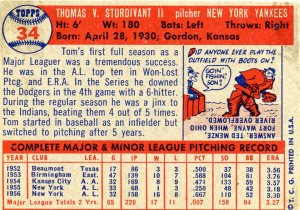

But in ’57 that message hadn’t gotten through yet, so there he is: that great New York Yankees starting pitcher…Tom Sturdivant?

As the bio suggests, he had a big year in ’56, 16-8, and a complete game six-hit shutout over the Dodgers in the World Series, which kinda got upstaged when Don Larsen went out and threw his perfect game the next day. But the point here is not the bio but the card number.

Tom Sturdivant is not card #25 in the 1957 Topps set. His teammate Whitey

Ford is. Sturdivant is #34, as the shown version of his issued card suggests. You’ll notice also that the cartoon quiz at the right side of the card has been changed from something about home runs in one inning, to a question about playing outfield with your boots on.

Again, not a true variation – the obverse of the Sturdivant back shows the Billy Martin front. I suppose somebody could have cut the cards apart and come up with a weird Martin/Sturdivant #25. If one ever turns up, now you know what it is.

There are two other “Sample” variations that jumped off (once it had occurred to me to start  looking for them). I’ll spare you the full 1959 Salesman’s Sample back, but here is the detail on the one card back shown.

looking for them). I’ll spare you the full 1959 Salesman’s Sample back, but here is the detail on the one card back shown.

It was a pretty good guess on the part of Topps: Nellie Fox would be American League MVP as his White Sox won the pennant for the first time in 40 years.

But the original design for the backs of the 1959 cards (or at least Fox’s) was decidedly different than what Topps wound up publishing.

The color design on the Sample card is green-and-black, and quite obviously the color design on the actual issued cards has been dramatically altered to the full Christmas design.

The color design on the Sample card is green-and-black, and quite obviously the color design on the actual issued cards has been dramatically altered to the full Christmas design.

The green “name box” has gone red, the black type in the bio has gone green, and the cartoon is now not just green and black, but red, green, with a salmon pink background.

Still, the other details of the card seem identical both in the preliminary and issued versions.

Not so for 1960. This might be my favorite of the bunch. There was a rationale, even for the changed number of the 1957 Sturdivant, for the inclusion of all the other cards shown here on the Salesman’s Samples. Through 1972, Topps cards were sold in numbered “series,” spaced out over the course of the spring and summer.

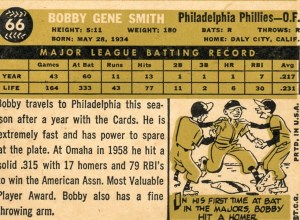

All the Sample cards were drawn from the first series – except in 1960. See that nice unspectacular version of #66, Bobby Gene Smith?

He would not be in the first “series” of 1960 Topps cards. Even though they had already mocked up a back for his card,  and evidently made no changes in it other than the by-now traditional color re-thinking, Smith was for some reason bumped from #66 to #194.

and evidently made no changes in it other than the by-now traditional color re-thinking, Smith was for some reason bumped from #66 to #194.

In the actual card set #66 is an obscure pitcher named Bob Trowbridge – it was not like there was some urgent need to drop somebody to make room for him. Sadly there are no files hanging around a back room at Topps annotating the arcane decisions about card numbers (though I know one later editor liked to give card number 666 to players who had hurt his favorite team). So we’re on our own figuring this all out.

Gary Carter, In Memoriam

It was 1988 and I was in my second month as the sports director of the CBS television station in Los Angeles and I was suddenly in desperate trouble.

The Dodgers were hosting the Mets in the National League Championship Series, I was doing the obligatory live sportscast from the field, and our prearranged interview with Orel Hershiser had suddenly blown up, five minutes to air, because manager Tom Lasorda had called a sudden team meeting. Orel was almost red with embarrassment but as I told him then, I wouldn’t have even thought about getting mad at him.

I don’t think Hershiser and I got animated or anything, and frankly I didn’t think anybody had even heard his friendly regrets, nor my friendly acceptance. But apparently Gary Carter of the Mets had been running past us, or something, as we spoke. Because as I turned around to try to figure out which of the Mets we might appeal to out of desperation, he was ten feet away and closing ground fast. He introduced himself – as if I wouldn’t have known who he was – and reminded me we had once done an interview while I was with CNN – as if I’d forgotten it. In point of fact, the first time I ever got paid to write about baseball players, the first time, was writing up the biographies on the backs of a set of baseball cards highlighting the stars of the International League in 1974, including the great catching prospect of the Memphis Blues, Gary Carter. I had known about him, and in a sense covered him, since I was fifteen years old. And Gary Carter was trying to pull my live shot out of the fire. “We’re supposed to be hitting,” he said. “But if Orel had to bail out on you, and you’re stuck for an interview, I can help you out.”

Just like that. Overheard that a guy he barely knew was in a spot, and he managed to shuffle a few things around – an hour before a game that helped decide whether or not his team would go to the World Series.

Because of this odd notion of his thatallof us on the field contributed to baseball’s success – not just the ones wearing the uniforms – some players called Gary Carter “Camera.” The premise was, he always knew where the camera was, and whether or not it was on him. In point of fact, I think his ceaseless cooperation with the media actually wound up hurting him in the Hall of Fame voting, as I think it has hurt Dale Murphy. The writers are afraid that voting in a guy whose geniality towards the media was legendary, but whose credentials could be interpreted as Hall/Not Hall, might look like favoritism.

We even talked about it in a tv interview in 2001. Of course he dismissed the idea. He was frustrated by being passed over for election, but still upbeat and enthusiastic, and he told me that if somehow his cooperation delayed or even prevented getting into Cooperstown, so be it. He wouldn’t have changed his attitude just to get another award, even if that award meant baseball immortality. As it was, Gary Carter had to wait until 2003 to get in to the Hall.

Today, after months of agonizing and dispiriting struggles with brain cancer, Gary Carter, a great catcher and leader and hard-nosed figure on a baseball field, yet simultaneously an aggressively nice man off it, passed away. And I am not ashamed to say it has left me in tears.

40 Years Of Steve Carlton

It remains, in short, the most amazing season a pitcher has put together since at least Sandy Koufax, and very probably since long before him. And now, Steve Carlton’s 1972 campaign, when he won 27 of his rotten team’s 59 games, dates to 40 years ago.

So much has been written about Lefty’s work that it is amazing to consider that an extraordinarily relevant detail is usually omitted from the recounting – one that makes winning 46 percent of one team’s entire supply of victories all the more remarkable.

Steve Carlton did it in a strike-shortened season.

The first sport-wide in-season strike in American history would in later contexts seem so brief as to be almost quaint. But when Opening Day was pushed back by a week forty years ago, and each team lost between six and nine games, it was traumatic – and it contributed to the distinct possibility that Carlton missed an opportunity to win 30 games.

The Phillies were to open in St. Louis on Friday, April 7 – 43 days after they had obtained Carlton straight-up from the Cardinals for Rick Wise – and were then to return for the home opener and an additional game against Montreal beginning April 10. They should’ve been in Chicago on April 14th, but that was the last of the six games which were wiped out, simply cancelled with no attempt to squeeze in make-ups nor compensate for the havoc of imbalanced schedules that would, among other things, largely decide who won the American League East that year.

One speculates about a small alteration in a large swath of history at one’s peril. Just because the guy got caught stealing does not mean the team would’ve scored two runs when the next batter homered. They could’ve pitched to him differently or they could’ve hit him or the guy standing safely at second at just that moment could’ve invoked a Rapture of some kind. Contemplating Carlton opening up against his erstwhile Cardinal teammates on April 7th instead of against the Cubs on April 15th is rife with hypothetical disaster. He might have hurt himself there, or begun the path to a bad habit, or not faced the right batter he challenged in just the right way to uncover the keys that led to his marvelous season. For all we know, if the players hadn’t struck and the games hadn’t been cancelled, Steve Carlton might’ve lost 27 games for the 1972 Phillies.

But it is deliciously intriguing to note that Carlton won all four of his starts against the Cards in his first season out of their uniform. With Phils’ skippers Frank Lucchesi and Paul Owens adhering pretty rigidly to a four-man rotation, Carlton would’ve pitched in the second home game against the Expos on April 12 – and of course Carlton also won all of his starts (three of them) against Montreal in ’72. But if the original schedule had been observed, that would have pushed his third start from April 15 against the Cubs to April 17 against the Cards, and it probably would have denied him the chance to start the last game before the All Star break. Thus if you buy any of the argument that the strike “cost” Carlton, it probably cost him one start and the most his theoretical full season should’ve netted him was 28 wins instead of the actual 27.

Of course, since we’re down the What-If rabbit hole, the real fun comes when we look at the 14 starts Carlton did not win, in route to 27-10.

The first stunning overarching truth about Carlton’s 1972 season was that he did it almost all by himself. He lasted through 30 Complete Games, and only three of his 27 wins were saved by other relievers. For contrast, when Bobby Welch won 27 for the 1990 A’s, the sport had already changed so much that all but seven of those wins had saves (19 by Dennis Eckersley) and Welch threw just two CG’s – both shutouts. Incredibly, Carlton blew the lead in one of his own non-win starts five times during 1972, and could only blame the tissue-thin Phillies’ bullpen for one other defeat snatched from the jaws of victory. Amazingly, Carlton endured a five-game losing streak beginning May 13th. His own error was the fulcrum in a 3-1 loss to the Dodgers and Claude Osteen at home that night, and the other games in the skein saw Carlton surrender at least three earned runs. The streak ended with a no-decision exactly a month later when Carlton helped cough up his own 5-0 lead to the Reds. Johnny Bench and Julian Javier homered in the 7th, but it was still 5-3 Phillies when Joe Morgan doubled off Carlton to lead the 8th. Reliever Chris Short let the inherited run score, and then Hal McRae touched him for the game-tying homer to start the 9th. The Phils would lose it in the 10th.

There were four occasions when just slightly more offense from the Philadelphia bats might’ve gotten him another win or two. On June 16th in the Astrodome he struck out a dozen and gave up just six hits and four walks in ten innings, but the Phils could do nothing with Don Wilson and Tom Griffin, and Dick Selma lost it in the 11th on a walk-off homer to Jimmy Wynn. On August 21st, Carlton again did marathon work without a win: 11 innings of seven hit, two run ball. He struck out 10 more, but the Phils turned nine hits and a walk off Phil Niekro into just one score, and Carlton’s 15-game winning streak was snapped. At Shea on September 24th, he gave up a lead-off homer to Tommie Agee and then watched John Bateman throw away a squib in the 8th, setting up the game-deciding sacrifice fly by the very non-immortal Lute Barnes in a 2-1 defeat (one of seven career RBI in a cameo career by the Mets’ second baseman).

But the best bet for another Carlton win probably came at Candlestick on July 15th. Carlton struggled through five, and was trailing 4-0 when Joe Lis pinch-hit for him. In the seventh, the winds changed and Phillies scored eleven off the Giants, and Bucky Brandon would vulture the win.

In short, we all knew as it happened that Carlton was creating something none of us had ever seen before. Just how special it was is only becoming clear now, with 40 years to ponder it.

The Heritage Of Alex Gordon

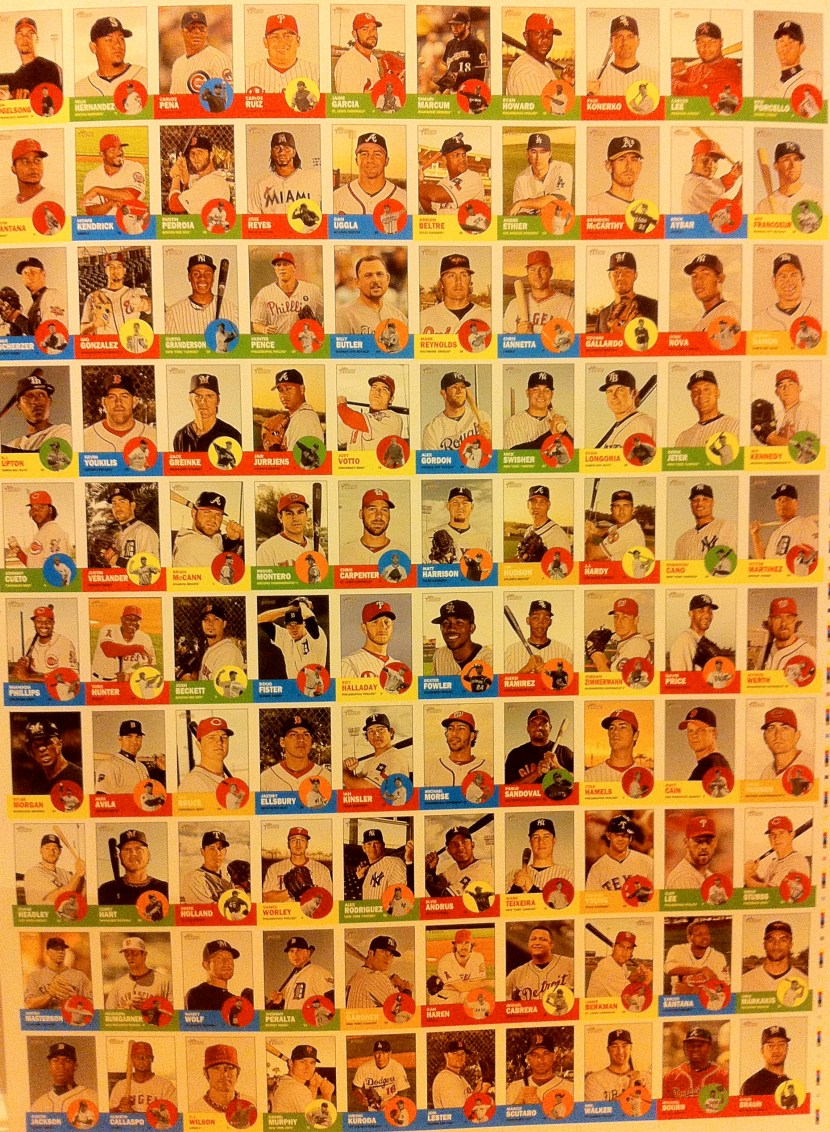

As a follow-up to the 10th annual “Topps Pack Opening Day,” I was studying the 2012 Heritage proof sheet by pals there were nice enough to provide. A familiar face showed up:

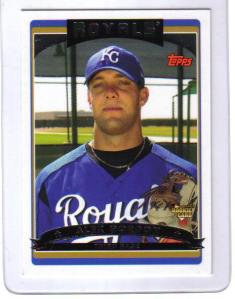

Last year, after a lot of hard work and a willingness to change what he had done all his life, the former collegiate superstar finally lived down his reputation as a man most famous for one of his baseball cards, and is now “just” a top flight hitter on what might quickly become a tremendous offensive machine in Kansas City, and this is “just” what his 2012 Topps Heritage Card #51 is going to look like.

Last year, after a lot of hard work and a willingness to change what he had done all his life, the former collegiate superstar finally lived down his reputation as a man most famous for one of his baseball cards, and is now “just” a top flight hitter on what might quickly become a tremendous offensive machine in Kansas City, and this is “just” what his 2012 Topps Heritage Card #51 is going to look like.

Even most non-collectors remember the brouhaha six years ago at this time when cards of Gordon appeared in the 2006 Topps and 2006 Topps Heritage sets – even though the MLB Players Association had recently codified the rules about who could and couldn’t be in big league card sets. It was comparatively simple: if you hadn’t already played a major league game, you couldn’t be included in a major league set. Topps, either accidentally (or many critics say, deliberately) got confused because that one rule meant Gordon – with 0 major league games under his belt – was eligible to be included in one of its brands, Bowman, but not eligible for its two others, Topps and Topps Heritage.

Gordon cards were made for all three sets and the MLBPA screamed bloody murder and just before the sets were released, the cards were supposedly pulled out of the packs of Topps and Heritage. The regular Topps set was released first, and cards of Gordon with a two-inch square hole in the middle started appearing in the packs (a ‘punch’ of some sort being used to destroy the inner portion of the cards while they were still on the uncut sheets, and the sheets were still stacked at the printers’). Not long after, full versions of the card appeared, some of them in packs shipped to PXs at American Military Bases in Germany.

If you think the thing with the Skip Schumaker “Squirrel” card is crazy, it pales in comparison to L’Affaire Gordon. I bought a few of the cards at four-figure prices on eBay, on the premise that this was the first regular Topps card ‘pulled’ from circulation since at least 1958. I was actually accused of being some sort of shill for the thing, because I consult on Topps’ retro issues; in point of fact I learned about the card’s scarcity on ESPN’s website, weeks after it came out. Topps estimated that maybe 50 to 100 of the Gordon cards got out, and maybe an equivalent number of ‘cutout’ cards. In the spring, however, a longtime dealer friend told me he’d been offered a large quantity of them. “I can get you 500 of them if you’ll pay the price.” Needless to say, I didn’t. As of this writing, there’s exactly one of them on eBay, but I’m confident that the number in circulation is closer to 1,000 than it is to 100.

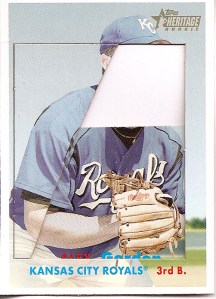

Weeks later, Topps Heritage hit the stores and sure enough, the #255 Alex Gordon appeared – but only in cutout form. This frame-like card still shows up at times, although only a few of the fragments from the cutout parts ever hit the hobby.

You can see from the little Frankenstein-like assemblage of parts here that there must’ve been a third “fragment” there bearing Gordon’s face. This was the only time Topps ever actually issued a jigsaw puzzle kind of card (although they experimented with a set of them in the early ’70s – and it bombed). One wonders if somebody opened a pack of 2006 Heritage and found these little pieces of junk without realizing what they were, and tossed them.

In any event, six years and five Alex Gordon Topps Heritage cards later (2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012), a full uncut version of the #255 2006 Heritage has never turned up. But I think it’s time for me to confess that I have one – sorta. We end as we began, with the fact that Topps indulges my long-standing fascination with their production process by donating the occasional proof sheet or printout to my Unintentional Museum.

So, for awhile now, I’ve had a paper proof version of the uncut 2006 Heritage Gordon. You’ll notice it looks different than the issued card – the proofs had red outlines, a “Rookie Card” logo, and the position designation had not yet been coordinated with the original abbreviations from the 1957 Topps set on which the Heritage cards were based. But, if you’ve ever wanted to see what the ’06 Heritage Gordon was supposed to look like… Ta da:

10th Annual Topps Pack Opening Day

For years, as part of my moonlighting as an unpaid consultant for Topps Baseball Cards, I have engaged in a ritual involving a few company executives and a few (brand new) boxes of that year’s Topps set. The first box to come off the production line is ceremonially opened, either on television or at Topps HQ, and then we quietly pillage through whatever’s available pack-wise.

Today we turned it into a happening.

This started when I ran into my colleague and fellow collector Greg Amsinger at MLB Network two weeks ago. Greg is giddy enough about cards that I once almost distracted him from a Yankee Stadium live shot by advising him that my collection included three Honus Wagners. When the Topps gang and I set the “ripping of the first packs” for today, I asked if I could invite Greg along.

Ka-boom.

Greg brought a camera crew, Topps put up a display including blowups of the cards of Pujols and Reyes in their new unis and the one-of-a-kind gold card inserts, they assembled the entire 2012 Baseball Production team, I dressed up in my Matt Moore First Win Game-Used uniform, they fitted up a conference room full of unopened boxes, and pizza, and I had to give a little speech, and half of the staff snapped photos on their phones and their tweets out even before I finished talking (insert your own joke here; I actually had to be brief for a change as I’m still under doctor’s orders to not try to ‘project’ with some severely strained vocal cords and throat muscles).

Suddenly we went from four guys sitting in a room going “nice shot of Braun” to a veritable orgy of pack opening. It felt like snack time at Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory and I must say, for something that was made ‘bigger’ than in years past at least in part to utilize the presence of a tv camera, this organically and spontaneously turned into a really fun ninety minutes in which the pride of the employees – to say nothing of the imminent promise of spring and another MLB season – were in full bloom.

Before we get inside the packs, and a really exceptional effort by Topps this year (to say nothing of a sneak peek at their next issue, 2012 Heritage) a couple of fun images.

The Topps production team all signed the first box that was part of the ceremonial presentation depicted above. They do it at aircraft factories and they do it on the first production runs at Apple – so why not? And on the right is that display I referenced complete with the Pujols and Reyes blow-ups. I have no idea how poor Amsinger, Cardinal diehard that he is, got past this graphic testament to the fact that Albert has surrendered his legacy in St. Louis and is now tempting the curse of Almost Every Angel Free Agent Contract Ever (Amsinger, when I pulled a Mark Trumbo card today: “It should say third base on his card. Where else is he going to play for them?” Me: “First. After you-know-what happens.” Amsinger: shakes head dolefully).

Over the last few years, Topps has been steadily improving the photo quality of their base set, but this year a great leap has been made. The photos are better sized and framed, more interesting, more innovative, and with the ever-increasing improvements in the mechanics of photography, crisper and more compelling. The embossing makes the names difficult to scan but the shots here of David Robertson and Jose Altuve are really terrific and virtually every square quarter-inch of the card frame is filled and filled cleanly. There’s a design decision here, visible in the Altuve card, to sacrifice the tip of his left foot to minimize dead space – and I think it works wonderfully.

And then come the fun cards. There are SP’s (single prints, if you’re not a collector – cards that you know going in are much scarcer than the regular 330 cards) that include Reyes and Pujols sent by the magic of computers into their new uniforms. When you consider that as late as 1990 Topps was still airbrushing the caps of traded players – literally hand-painting logos over the original one, not on a photograph, but on a negative measuring 2-1/2 x 3-1/2 inches) – let’s give the computer a round of applause.

computers into their new uniforms. When you consider that as late as 1990 Topps was still airbrushing the caps of traded players – literally hand-painting logos over the original one, not on a photograph, but on a negative measuring 2-1/2 x 3-1/2 inches) – let’s give the computer a round of applause.

The flatfootedness in the Reyes card makes it a little clunky but it gives you a pre-Spring Training hint at how the new Miami uniforms are going to visually ‘feel’ once the rechristened club takes the field.

Two years ago the theme of the SP’s were the Pie-In-The-Face celebrations, mostly enacted by the Yankees’ A.J. Burnett. This year the premise is celebrations and mascots, and in the case of the former, particularly the Gatorade Bath:

Butler, caught just as the orange goop explodes but before he’s lost under it, is a classic card. But, to my mind, the SP version of Mike Morse’s card 165 and its suspension-of-the-wave is an instant All-Time Great:

But 48 hours after the cards reached dealers and collectors, most of the publicity has surrounded the short print of #93 Skip Schumaker.

The Cardinals’ second baseman is said to be ticked off – and I happened to see Kevin Millar, serious for the first time in months, take unnecessary umbrage at the St. Louis Rally Squirrel squeezing Schumaker  out of frame – but remember, for every one of those cards, there are several hundred of the regular one on the right here. Happy? Nice boring five-cent card compared to one that’s rather crazily being bid up to more than $200 on eBay?

out of frame – but remember, for every one of those cards, there are several hundred of the regular one on the right here. Happy? Nice boring five-cent card compared to one that’s rather crazily being bid up to more than $200 on eBay?

Players take the baseball card photo a lot more seriously than they would have you believe. Several inscribe cards bearing particularly unflattering pictures with notations about how much they hate the photo. On occasion players won’t even sign their cards based solely on the choice of image.

The real trick for the Schumaker SP 93 will be not to get the player to sign it – he’s noted for a good heart, I’m sure the charity possibilities will be raised to him and he’ll sign a bunch. The problem is going to be getting that Squirrel to sign the card. Incidentally, the squirrel isn’t a Topps first; a card of “Paulie Walnuts,” a squirrel who occupied a foul pole at Yankee Stadium, was issued in 2007.

I promised a preview of Topps Heritage 2012 and that’s coming – but one more aside first. I thought I’d pay off the day I scared Greg Amsinger with my Wagner boastfulness by bringing the famed T206 scarcity to Topps to link up the past and the present. He didn’t know it was coming, which is why he’s been caught mid facepalm on the right.

I promised a preview of Topps Heritage 2012 and that’s coming – but one more aside first. I thought I’d pay off the day I scared Greg Amsinger with my Wagner boastfulness by bringing the famed T206 scarcity to Topps to link up the past and the present. He didn’t know it was coming, which is why he’s been caught mid facepalm on the right.

And lastly, Heritage. They’ve done another meticulous job matching up the set celebrating its 50th anniversary, the vibrant 1963 design, in which the glowing colors of ’60s Topps were first evident:  A lot of star players on this sheet – and forgive the waviness of the photo: it’s a sheet.

A lot of star players on this sheet – and forgive the waviness of the photo: it’s a sheet.

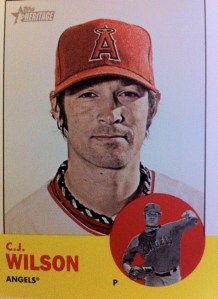

Two cards in particular jumped out at me: Reyes again in what looks like a photo actually shot at the news conference announcing his move to Miami (although that could easily be a little misdirection) and C.J. Wilson in Angel garb.

Two cards in particular jumped out at me: Reyes again in what looks like a photo actually shot at the news conference announcing his move to Miami (although that could easily be a little misdirection) and C.J. Wilson in Angel garb.

One note on deadlines: Chris Iannetta is shown with the Rockies in the Topps set, but has already been updated to his new Angels’ uniform in the Heritage issue.

Montero-Pineda: No Big Deal?

The reaction to the Pineda-Montero trade is unanimous: Everybody seems to believe it was a hugely significant deal, but a ripoff of biblical proportions. Unfortunately, I have yet to read consecutive analyses saying who did the ripping.

My concern is the other part. Ever the contrarian, I am not convinced this is an epic trade, nor a rip-off. I’m not convinced by either of these guys.

I suppose the confusion originates with the similarly disparate conclusions about Montero’s ability to survive on the major league level. Before he hit the Bronx last September there was no middle about him. He was either the next great slugger and at least a sufficient catcher, or an overrated stumblebum whose ceiling might be Jake Fox.

I don’t think September cleared things up for us. He drove in a dozen runs and slugged .590 in 61 at bats, and showed the kind of jaw-dropping opposite field power off the middle-to-high fastball that seems to appear only once per decade. But as the Yankees cruised towards the division title amid the Red Sox collapse and a Rays surge that could never have threatened them, they trusted Montero to start exactly one game behind the plate. He wound up catching thirteen more innings in two other games and four of five baserunners stole off him. He did not impress defensively.

Nevertheless, the real question mark should be how New York used him – or didn’t use him – in its post-season cameo. Yes, Jorge Posada got on base eleven times in 19 plate appearances (five singles, four walks, a hit batsman, and a triple) but he didn’t drive in a single run and six of his eight outs were whiffs. It is intriguing that only one of the hits, only one of the walks, and the lone HBP came in the two Yankee wins (9-3 and 10-1 wins no less). Posada’s fireworks were mostly empty calories. Montero, meanwhile, appeared only in the rout portion of the latter and went 2-2 with an RBI.

The Yankees also just traded a bat when the forecast for their 2012 production is not optimistic. Alex Rodriguez slowed to a crawl last year, Curtis Granderson vanished in late August and Russell Martin long before that, Nick Swisher was all over the place, and there is only one Robinson Cano. I realize Joe Girardi envisions the DH spot as a place to park the fading Rodriguez or the beaten-up Swisher on a given day but this “keep ’em fresh” use of the DH implies that the batters you’re going to use there are still of value. To me, the Yankee batting order got almost spasmodic in the second half of last season and a great young power-hitting bat in its middle would be far more useful than another young starting pitcher.

That is, if the Yankees really believed Montero was a great young power bat. I’m convinced that for all of Brian Cashman’s comparisons of Jesus Montero to Miguel Cabrera and Mike Piazza, he has decided that there is some grave flaw not just in his glove but in his bat. Cash was reportedly ready to trade Montero to Seattle for Cliff Lee in 2010 but balked at trading Montero and Eduardo Nunez (this was confirmed for me last summer by another Major League GM). Cashman has been surprisingly willing to trade this supposed blue chip prospect for whatever the drooling Mariners would surrender. It was suggestive enough that he seemed to value Nunez more highly than Montero. And now, if he just traded a Cabrera or a Piazza for a Michael Pineda, he’s an idiot – and I don’t think he’s an idiot.

And I’m giving Pineda the benefit of the doubt here. I was first astonished by this guy’s potential during a throwaway appearance at the end of a televised Mariners’ game late in spring training 2010. His spectacular start to 2011 was no real surprise to me, and I’m assuming even though they cuffed him up for three earned on five walks and three hits in five innings at Seattle on May 27th, the impression was left on New York brass that this was one of the coming mound stars of the game. After all, before that start at Safeco, Pineda had been 6-2, with 61 K’s in 58-1/3 innings. He’d only given up 46 hits and only twice had walked more than two men in a game.

Pineda went 3-8 thereafter.

He was still good in June, and what followed could very easily have been exhaustion – except he had managed 139 innings pitched in the minors in 2010 and 138 two years before that. This was not totally foreign territory. And yet he collapsed at the All-Star Break:

GS IP ER BB K HR W L ERA WHIP G/A OA

Before 18 113 38 36 113 10 8 6 3.03 1.04 0.84 .198

After 10 58 33 19 60 8 1 4 5.12 1.38 1.38 .236

Look, a 1.38 WHIP is not going to kill you, not with the Yankees. Consider that for all the disappointment the second half tacked on to his rookie season, Pineda got run support of 5.16 for the season (Derek Lowe/Dan Haren/Chris Carpenter territory). The Yankees gave all of their guys a lot more help: Ivan Nova 8.82, Freddy Garcia 7.49, A.J. Burnett 7.19, CC Sabatha 6.98, and Bartolo Colon 6.41.

But there is another disappointing set of splits to consider. Pineda not only did better in the pitcher’s paradise that is Safeco, but he did better in a supremely bizarre way.

Michael Pineda’s home-road splits:

GS IP ER BB K 2B 3B HR W L ERA WHIP G/A OA

Home 12 77 25 28 82 3 0 9 5 4 2.92 1.01 0.92 .182

Away 16 94 46 27 91 21 2 9 3 4 4.40 1.17 1.05 .234

Do you see it?

Michael Pineda surrendered only 12 extra-base hits at home, exactly one a game. On the road, he gave up 32 of them, exactly two a game. The homers are the same but the doubles helped to kill him.

Another stat to throw at you. His BABIP (for the un-SABRized, the opponents’ Batting Average on Balls hit In Play) was .258. That was the ninth lowest in the majors last year, and while having the ninth lowest opponents’ batting average on anything would intuitively be a good thing, in this case it ain’t. The BABIP for all pitchers combined was .291, which implies that on as much as thirteen percent of the outs Pineda got on balls the hitters hit, Pineda was lucky they were outs. Low BABIPs (or high ones) tend to correct themselves over the course of a season, or from one season to another, which is as good an explanation for his opponents’ actual batting average to jump by .038 after the All-Star Break as is “he got tired at 113 innings.”

There are a lot of numbers in here, but between Pineda’s second half (and road) woes, and the Yankees’ remarkable unwillingness to put Montero on the spot in the playoffs, I infer that this wasn’t a rip-off, and it wasn’t a trade of future Hall of Famers – that it might have just been the trade of a couple of high-ceiling but deeply flawed ballplayers.

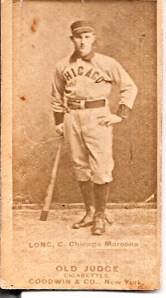

Name Dropping Herman Long

Had the pleasure of joining Brian Kenny on MLB Network’s Clubhouse Confidential yesterday (more on that below) and as we batted back and forth the necessity of electing Gil Hodges to the Hall of Fame, Brian mentioned that if he gave me a chance I could drop a lot of 19th Century Cooperstown-worthy players. I had time to say only “look up Herman Long.”

I’ll detail his Hall credentials in a moment. But first: for all of the weird HOF elections of the first 75 years, he is in the middle of the weirdest. Take a look at the results from the first-ever Veterans’ Committee vote, conducted in 1936:

- Buck Ewing 39.5 Votes, Elected 1939

- Cap Anson 39.5 Votes, Elected 1939

- Wee Willie Keeler 33 Votes, Elected 1939

- Cy Young 32.5 Votes, Elected 1937

- Ed Delahanty 21.5 Votes, Elected 1945

- John McGraw 17 Votes, Elected 1937

- Old Hoss Radbourn 16 Votes, Elected 1939

- Herman Long 15.5 Votes

- King Kelly 15 Votes, Elected 1945

- Amos Rusie 11.5 Votes, Elected 1977

- Hughie Jennings 11 Votes, Elected 1945

- Fred Clarke 9 Votes, Elected 1945

- Jimmy Collins 8 Votes, Elected 1945

- Charles Comiskey 6 Votes, Elected 1939

- George Wright 6 Votes, Elected 1937

So there were 78 ballots, 60 different players got votes, half of them eventually wound up in the Hall, but the guy who got the eighth most, who finished ahead of 23 future Hall of Famers, not only never made it but never again got significant support? I mean, in the 1937 Veterans’ Committee ballot, Long got one vote.

Something is very, very strange here. I mean, while we think of the stars of the 19th Century and the early 20th as having played in some kind of baseball version of the Pleistocene era, consider who the 1936 voters were. If this were January, 1936, Bob Costas would’ve made his NBC baseball debut in 1907, I would’ve covered my first World Series in 1900, Peter Gammons would’ve broken in with The Boston Globe in 1893, and Tim McCarver would’ve started with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1883.

In short, the 78 members of the Veterans Committee of 1936 saw most of the antediluvian names on that ballot play either professionally or as kids (let’s just play with that again: if this were 1936 I’d have seen my first MLB game in 1891 and I believe Peter’s first would’ve been in 1882). These guys thought of Herman Long in the same breath with the most famous player of the 19th Century (King Kelly), the man who won 59 games in one season (Hoss Radbourn), and the man who played or managed 14 pennant winners (John McGraw). For further context, there were six players to whom the first Veterans voters gave exactly one vote each, who wound up in Cooperstown and to some degree in the baseball public’s awareness, like 342-game winner Tim Keefe and the inventor of the curveball Candy Cummings. And Herman Long got 15 times as many votes.

So who was this guy?

Derek Jeter is the Yankee shortstop now, but Long was the first. His 1903 Breisch-Williams baseball card; the photo shows him from Boston circa 1899

Herman Long was the great shortstop of the Boston Beaneaters’ dynasty of the 1890’s. He produced four consecutive years of an OPS of .800 or higher, had two 100-RBI seasons, six 100-Run seasons, and in a time without home runs, he hit 91 of them over 13 seasons including a dozen in each of two years. He stole 537 bases (that’s still 30th all-time) and scored 1,456 runs (77th all-time). In that measure of what an individual player’s offense and defense was “worth” to his team, “WAR,” Long finished with 44.6 (his Hall of Fame teammate, third baseman Jimmy Collins, finished at 53, and his Hall of Fame teammate, centerfielder Tommy McCarthy, finished at just 19). And despite having made more errors than anybody else in history, he has the 122nd best Defensive WAR+ among all position players ever. Boston’s two spurts – at the beginning and end of the 1890’s – produced five pennants and Long was the shortstop on all of the teams.

His nickname was “The Flying Dutchman.” When they began to use it late in the 1890’s for a kid named Honus Wagner, it was a tribute to Herman Long. More trivially, he would later play only 22 games there, but he was the first shortstop of the New York Yankees (then the Highlanders).

Is Long a Hall of Famer? I’m not sure. But he was considered the 8th best player among the “Old Timers” in 1936, and then fell into a black hole. It wasn’t even a matter of public scandal or diminished rotation – Long had been dead since 1909. He certainly merits consideration.

Remind me to tell you later about Bobby Mathews.

SPEAKING OF OLD TIMERS

Returning to the topic of my visit to MLB Network, if you didn’t know, that’s where my erstwhile employers MSNBC were headquartered from 1996 until October, 2007. I worked in this very building from September of ’97 through December of ’98, and then again from February of ’03 until we moved out. Yesterday was my first day back and it was mind-blowing. Baseball invested a reported $54,000,000 to upgrade the facility with rebuilt studios and state-of-the-art technology.

But they changed almost nothing else.

Not the carpets. Not the desks. Not the chairs. Not the make-up rooms. Not the cubicles. Not where the large clusters of desks are. Not the cafeteria. Not the offices. Not the office door plates. Not the “Employees Must Wash Hands” signs in the bathrooms.

Going into it was like one of those dreams you’ve probably had where you walk into some place totally familiar to you – your childhood home, or where you live now, or go to work, or school – and in the middle of it your unconscious has placed a nuclear reactor or a jungle or something else utterly incongruous, without changing even one other thing.

You think I’m kidding? My old offices, the one from 2003 and the one from 1997, are still offices, with the same doors, windows, nameplates, and televisions. The newer of them is occupied by an old colleague of mine from Fox Sports named Mike Konner, and to my amazement I found that on what is now his wall was a poster from MSNBC’s 2004 Campaign Coverage. I remembered this one distinctly, because there was controversy over some of the people shown in the back row (somebody wasn’t under contract, or somebody was left out, or something), and the thing was immediately replaced by a revised version with somebody else’s body swapped in. As I saw it hanging on Mike’s wall I remembered I had left the rare “uncorrected” version in a pile of junk when I left.

So why was it on Konner’s wall? I asked Mike where he found it. “It was here when we moved in. In a pile of junk.”

Every time I think of him saying that, I laugh. The poster has been in that tiny office since 2004.

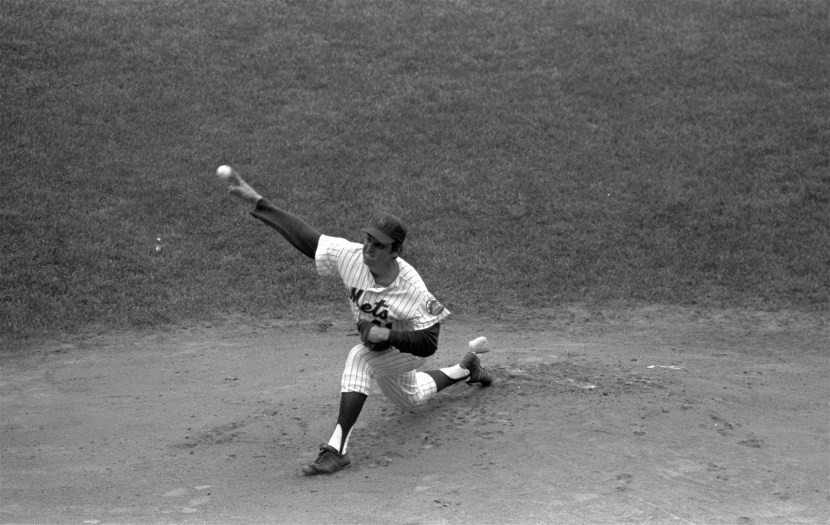

Seaver And Mathewson

On his MLB Network program Studio 42, Bob Costas tonight referenced a blog post here from 2009, and asked Tom Seaver if he was aware that I’d found a game-action photograph of Christy Mathewson from the 1911 World Series that showed Mathewson using the exact of drop-and-drive delivery Seaver brought to perfection in the early years of his career in the late ’60s.

Seaver said he’d seen the photo – I was pretty sure he had, since I’d sent a copy to him via a friend shortly after I found it in Cooperstown.

In blog years, a long time has passed since I posted the shots, so here they are again:

That’s Seaver – coincidentally in action against at Shea Stadium the San Francisco Giants in 1975 – showing the “drop and drive” that usually left the front of his right knee dirty. There had been a lot of anecdotal evidence that Mathewson, who retired in 1916, had used a similar delivery. But until the kind curators at the Hall photo archive let me look at their collection of glass images from the 1911 World Series, I don’t think anybody had actually seen a game-action image of Mathewson.

The resemblance, as you’ll see, is startling:

It’s the same delivery. In 1911.

Needless to say, I geeked out completely when I saw that photo. I literally thought “Why is there a picture of Tom Seaver pitching in the 1911 World Series?” After I posted the shot in August, 2009, I ran into Bob at Yankee Stadium and he had seen the post and he geeked out completely over it.

Just for the record, there are precious few game-action photos, particularly of pitchers, particularly in post-season action, from before the first World War. This was part of a series of 30 or 40 transparent glass slides, above three by five inches, that had been taken with a special camera for presentation as a slide show at the earlier movie theaters of the time. The Hall has what appears to be a complete set, and it constitutes a treasure trove for historians. You’ve heard of “Home Run” Baker? He got his name not for volume of homers, but for consecutive game-winning blasts off Mathewson and his fellow future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard in the ’11 Series. The slides include images of Baker rounding third on one of the homers.

I’m not going to say there isn’t another game-action photo of Mathewson anywhere else (and I’m not counting all the posed and/or warm-up shots that show Matty fully upright or just soft tossing). I’m just saying I’d never seen one before this image, and I don’t recall anybody reporting having seen another.

The 1911 photo series had been lost to historians because when it was donated to the hall in the mid 1960’s, the individual slides were divvied up and put, one by one, into the individual files of the players depicted. Only around 2009 was a search made for the whole set (you can imagine how long that took). This is what the Mathewson photo looked like – exactly as movie-goers would have seen it in October or November, 1911:

This is magnificent for several reasons – not the least of which is the extraordinarily low mound (which makes you appreciate Mathewson’s 373 career wins (plus five more in World Series action). But principally because that which historians thought really hadn’t become the standard for the “power pitcher” until the ’40s or ’50s, was in Mathewson’s repertoire a century ago.