Category: Dailies

A Bat, A Boy, Some Batting Gloves, And Evan Longoria

The cry from behind the Rays’ dugout was not the most common one, but it’s not like Evan Longoria had never heard it before.

“Evan!,” the young boy bellowed. “Can I have your batting gloves?”

Longoria, out by the batting cage on McKechnie Field in Bradenton, decided to engage. “I need them to hit. What am I supposed to do when I hit?” The boy looked back, startled and without riposte. “Yes. I’m talking to you. About batting gloves. I mean, if I give them to you, what do I use? Can I use your instead?”

Now the boy was back on more familiar ground. “My batting gloves are in my bag in the car.” Longoria played peeved, but evidently was, in fact, charmed.

“Maybe I should give you everything I use. Gloves, bat, cap. I just won’t hit.”

The boy became thoughtful. “No, don’t do that.”

Seemingly the end of the exchange, and Longoria went ahead and hit. And as soon as he finished, he ambled back to the Rays’ dugout without looking at the boy. And he popped back up and slapped a bat on the dugout and, with a big smile, pushed it towards the youngster, and raced off to shag fly balls before the boy or his mother could even say thanks.

OTHER EVENTS OF THE DAY, ILLUSTRATED: Manny Ramirez leads the Rays in humiliating skipping drills that the strength and conditioning staff insists are really some kind of exercise.

Manny Ramirez leads the Rays in humiliating skipping drills that the strength and conditioning staff insists are really some kind of exercise.

The generations mingle during Pitchers’ Fielding Practice. If the gentleman on the right is not instantly recognizable, you missed the 50th Anniversary celebrations last October.

Lee: Great – McGee: Lights Out

Notes from the Philadelphia-Tampa Bay exhibition in Clearwater: The Rays’ dance card wasn’t exactly full – no Longoria, Ramirez, Damon, not even Ben Zobrist. But Cliff Lee didn’t break a sweat over four innings this afternoon in Cleveland: no walks, two singles, five strikeouts (including two in his last inning)…the Rays are trying to manage expectations but if you had to name the guy who’d lead them in Saves this year, you could do worse than predicting rookie Jake McGee. McGee not only struck out Shane Victorino and Raul Ibanez in consecutive at bats in the 5th, but Victorino was so fooled that he lost the bat and it helicoptered fast enough that in the on-deck circle, Ibanez hit the deck and the bat continued twenty rows into the crowd…as mentioned Manny Ramirez wasn’t in the house but the Rays are impressed with his apparent revitalization. It’s as if somebody got a wake-up call that his career will not last forever and he wants “Manny being Manny” to sound a little more positive than it has the past three seasons…one of the Phillies’ two biggest problems was underscored in the second and third innings. They collected six hits and got a wild pick-off throw into centerfield, but scored  only three runs, and two of those were on solo homers by Howard and Schneider…To the left -this is not much of a picture of Rays’ catcher Nevin Ashley, back in camp for a second straight year and 0-for-2 in relief of Kelly Shoppach in his bid to make it as the back-up receiver – but that’s not the point. The point is that he married a woman named Ashley, and she decided to follow tradition and identify herself by her husband’s name. She is Ashley Ashley…An image that will disturb Cubs’ fans, even though he did start with the Phillies. They had their new AAA manager coach third base today. Fella named Ryne Sandberg:

only three runs, and two of those were on solo homers by Howard and Schneider…To the left -this is not much of a picture of Rays’ catcher Nevin Ashley, back in camp for a second straight year and 0-for-2 in relief of Kelly Shoppach in his bid to make it as the back-up receiver – but that’s not the point. The point is that he married a woman named Ashley, and she decided to follow tradition and identify herself by her husband’s name. She is Ashley Ashley…An image that will disturb Cubs’ fans, even though he did start with the Phillies. They had their new AAA manager coach third base today. Fella named Ryne Sandberg:

And greetings from Florida from one of baseball’s best minds, and best guys, and somebody who was fortunate enough to visit with him:

Bryce Harper: “I Want To Kick The Crap Out Of You”

“Gonna remember that first RBI for a long time?,” a reporter asked Bryce Harper.

“Gonna remember that first RBI for a long time?,” a reporter asked Bryce Harper.

“‘Scuse me?” Harper deadpanned up from his seat in front of a locker in the visiting clubhouse at George M. Steinbrenner Field.

The reporter tried again: “Are you going to remember that first RBI?”

“Did I get an RBI?” Harper’s act had reached its end and he smiled broadly. “Just kidding! Yeah.”

It had come in the 8th inning of a sloppy 10-8 Washington victory over the Yankees, off the prototypical AAA pitcher, Romulo Sanchez. But the single to right made the loudest sound of any ball connecting with any bat all day, and it was probably not coincidental that rightfielder Colin Curtis then bobbled it.

It’s not as if they’re going to put a plaque up to indicate it happened, although it was noteworthy that when Harper went into the game in the bottom of the 5th, as he jogged out to right, the other team’s crowd applauded loudly, as they did for his two plate appearances, as they did when he first emerged on the on-deck circle.

The first ribby also inspired remarkable perspective on comparative quickness. We will each have our own perspective on October 16, 1992. It was the day of the book party for Madonna’s $50 book of naked pictures of herself. The next day, Tom Glavine would four-hit Toronto to open the World Series. It was three weeks until Bill Clinton’s first presidential election. I had already been working at ESPN for ten months, Derek Jeter had already played 58 games in the minor leagues, and one of Harper’s current Washington teammates, Matt Stairs, had already played 13 games in the major leagues.

Harper said, with full sincerity: “It takes awhile.”

Harper said, with full sincerity: “It takes awhile.”

He was referring, of course, to the “30 to 40 at bats to get yourself ready,” during spring training – and not the seemingly lightning route that has put him in a major league camp at the age of 18 years and not even five months.

That route seems to challenge the expectation that Harper will have seen three Spring Trainings before he appears in a big league game that counts. It is noted that at this time in 2013 he will still be a young 20 year-old and that’s quick enough. Except the ball explodes off his bat and his adjustment to the outfield has already been such that he was as proud of starting a relay that nailed the Yankees’ Austin Romine at third base as he was of the RBI hit (shown to the left in what you’d say is a crappy photo, until you realize it was taken from the distant press box with an unaided iPhone).

Many newly-official men have looked like star big leaguers at 18. To go back to placing Harper’s birth in perspective, the ill-fated Yankee phenom Brien Taylor had already struck out 187 guys in his first 161 innings of pro pitching the day Harper was born. But it is hard to believe the Nats would arbitrarily slow down his pace through the minors to stick to an artificial deadline of 2013, because it isn’t just Harper’s physical game that’s so impressive.

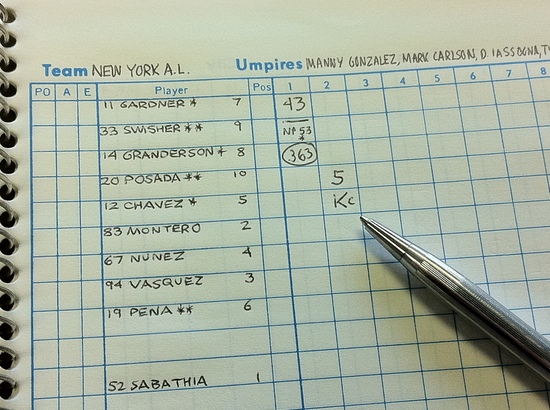

His attitude is also already pretty well developed. Harper was asked by the small crowd of reporters around his cubicle what he thought of playing in a packed stadium festooned with Yankee self-promotion, and he admitted it was “awesome” to have shared a field with Jeter and Alex Rodriguez and CC Sabathia and all the rest. He said “awesome” twice and added Nick Swisher to the pantheon of impressiveness, which should make Swisher say funny things later on.

But then Harper was asked if he’d said hello to any of these Yankees (even Swisher, who was almost 12 when Harper was born). “No. I don’t really care to say hi to anybody over there. I stick over here.” I wondered if that was humility or competitiveness. “You try to beat ’em. That’s what I am. If we’re off the field? Hey, I’ll go and say hello. You can be my best friend off the field and I’ll hate you on the baseball field. That’s how I am…on the field, I want to kick the crap out of you.” (By the way, here’s Dave Sheinin’s version of this in The Washington Post, including the very relevant detail that Harper grew up around Las Vegas as a Yankee fan).

One game, one portentous spring training, one killer instinct, and one exhibition game RBI do not mean you should step directly into the majors at 18. But they do tend to support the idea that suggesting it is theoretically possible at 19 is not at all crazy.

A LITTLE PHOTO TOUR OF (MY) SPRING TRAINING OPENER:

Take a nice deep breath:

An almost-forgotten pre-game ritual: The visiting team taking infield (and outfield) practice. The catchers are Derek Norris and Jesus Flores, the coaches Jim Lett and John McLaren. When I asked Washington manager Jim Riggleman about this, he said there was nothing better for a team before a game. “But on the road, the groundskeepers look at you like you’re crazy! ‘Get off our field!'” It looked to both of us like none of the Tampa groundskeepers had been alive the last time a big league team taking infield on the road, which may have gone out with Earl Weaver:

The Ironies Of The Late Duke Snider

It is, as ever, summed up perfectly by Vin Scully:

“Although it’s ironic to say it, we have lost a giant.”

Beyond the sadness of the passing of The Duke of Flatbush, Edwin Donald Snider, is the reminder that his career was filled with irony. As the top Dodger prospect of the late ’40s he was considered a temperamental bust. By the time of his passing today he was considered one of the game’s most personally revered gentlemen, and long before, by the time the Dodgers left Brooklyn, he was considered one of the elder statesmen of the sport, his prematurely-silver hair and hint of sadness in the eyes seemingly reflecting the tragedy that was the move of the franchise.

Therein too lay an irony. Duke Snider was a Southern Californian through and through. Alone among the key Brooklyn Dodgers, he was going home to Los Angeles. And yet he expressed only sadness and regret about that, and during his brief coda season with the Mets in 1963, was welcomed home to New York more loudly than any other of the “exes” – Casey Stengel included.

There is also something tremendously ironic about the iconic status included in Terry Cashman’s “Talkin’ Baseball” song. Despite the premise of “Willie, Mickey, and The Duke,” the Baseball Writers needed eleven tries to get his election to the Hall of Fame right. In his first year of eligibility, Snider got just 51 votes – a stunning 17 percent. As late as 1975 he was under 40%.

The writers dismissed Snider, as they did nearly all the Dodger offensive stars, because they felt Ebbets Field provided some kind of extraordinary advantage and because the Dodgers lost so many ultimate games. Gil Hodges is still – criminally – not in Cooperstown in part because of this prejudice. In point of fact, Snider hit just 37 more homers in Brooklyn than on the road in his Ebbets Field years (discounting partial seasons, that’s an average of four or at most five more a year – a meaningless statistical variable).

Hodges has still not gotten his due; Snider and Pee Wee Reese struggled for it; Carl Furillo has never been taken seriously. It is amazing to contemplate that Snider’s Dodgers were somehow penalized because between 1946 and 1956 they won only the one World Series, while losing five of them, and losing two special NL playoffs, and losing yet another year (1950) on the last day of the season. That was painful stuff to be sure, but what it meant was, that for every year for a decade (excepting 1948) the Dodgers gave their fans, at worst, a team that made it to “the final four” – and with key parts of the Brooklyn franchise still at work in Los Angeles, added World Championships in 1959, 1963, and 1965.

This is a time for condolence and mourning and I don’t mean to at all take away from that. It’s just that the passing of a great and good baseball man like Duke Snider reminds me that the injustice of the undeserved undermining of the reputation of a player, or a team, should also not be forgotten.

Aaron And Gibson Lefthanded, and The Wrong A-Rod (Revised)

Hank Aaron’s appearance this week on The Late Show With David Letterman not only brought as hearty a series of laughs from baseball’s real all-time homer champ as I’ve ever heard him produce, but it also added one of those delightful footnotes to history. Letterman claimed that the day Aaron homered off Jack Billingham of the Reds to tie Babe Ruth’s mark of 714 at Riverfront Stadium in 1974, he was in the crowd. There’s no reason to doubt it: that was the year between Letterman’s career as a tv weatherman and the start of his comedy writing and performing.

Hank was there to provide the briefest of plugs for Topps’ celebration of its 60th year in baseball cards (he presented Letterman with a one-of-a-kind card in the style of the 2011 set, complete with a diamond in it – 60th being the ‘Diamond Anniversary’). For the sake of disclosure, Topps is paying Mr. Aaron to do the publicity, and for the sake of further disclosure, I’m an unpaid consultant for Topps as well.

They did not discuss two of Aaron’s more interesting cards. Obviously the portrait on the 1956 card here is the young Henry. But who is that sliding into the plate, an “M” on his cap and nothing on his uniform?

Correct. It’s Willie Mays sliding home, his uniform doctored to kind of look like a Braves’ jersey. There’s no special value to that mistake, because they never corrected it. In fact I don’t know if it’s considered a mistake – I think “fudge” is a better term.

The 1957 edition, meanwhile, is a beautiful thing and NBH (Nothing But Hank)…but as the old cliche goes: what’s wrong with this picture?

The “Lefty Gibson” card is seldom seen and thus reproduced here in full: If you can imagine this, Topps prepped its first series of 1968 cards in the winter of ’67-68 and not only did Gibson succeed in this stunt, but so did Seaver, who had tried it while posing for his very first card.

If you can imagine this, Topps prepped its first series of 1968 cards in the winter of ’67-68 and not only did Gibson succeed in this stunt, but so did Seaver, who had tried it while posing for his very first card.

Each got all the way to the printer’s proofs level – just a handful of sheets printed. Then the Topps Copy Editor had his apoplectic attack and replaced both the Gibson and Seaver lefthanded pitching poses with nice tight portraits.

For years Topps has taken the rap for the mistake – there have even been understandable suggestions of an ethnic slur implied by the screw-up. In fact, it wasn’t entirely the company’s fault. In the winter of 1967-68, the newly-powerful Baseball Players Association was squeezing Topps into dealing with it, rather than on a player-by-player basis. Topps, which theretofore had been able to sign guys for a down payment as low as a dollar, resisted. The MLBPA promptly forbade its members for posing for Topps during Spring Training, and in fact throughout the entire regular season, of 1968.

Thus, guys who changed teams in ’68 or the ’68-69 off-season are shown hatless in old photographs in the first few series of the 1969 set. But 1968’s rookies for whom Topps had no photo? It had to get them in the minor leagues (the Topps files were filled with photos of nearly every Triple-A player in 1968), or buy shots from outside suppliers. At least a dozen images in the ’69 set, including Reggie Jackson and Earl Weaver – and “Aurelio Rodriguez” – were purchased from the files of the famous Chicago photographer George Brace. Somebody at Topps should’ve known, but the original Rodriguez/Garcia goof appears to have been Brace’s.

Incidentally, eight years later Garcia got his own card under his own name, in the Cramer Sports Pacific Coast League Series. By this point he was the trainer of the Angels’ AAA team in Salt Lake City. The biography on the back makes reference to the 1969 Topps/Brace slipup.

Pitchers Warmed Up…Where?

Veteran baseball people were barely done scratching their heads at the sudden rush to declare Opening Day starters in February – to tentatively hint at a violation of the mix of superstition and inchoate fear they call “tradition” – when injury claimed a pitcher who was merely scheduled to start the Spring Training opener.

Adam Wainwright may not only miss pitching in this Cardinals’ camp; he may not experience Spring Training again until 2013. The ligament damage near his elbow is profound enough to shelve him until sometime during the ’12 season, and could have as big an impact on a team and a franchise as any such injury in recent history, maybe since Sandy Koufax’s retirement put the Dodgers into a funk that lasted eight seasons. Not only does it neuter a Cardinal team that fell behind Cincinnati last season, and Milwaukee last off-season, but it could even impact the team’s ability and willingness to commit huge money to Albert Pujols next off-season.

The larger question pertains to the feeling that these injuries happen more now than they did ‘in the past.’ This question itself has been around long enough to become a baseball tradition of sorts. Surely they don’t happen that much more often. Koufax quit before his fragile elbow might have snapped like a twig. Don Drysdale retired in mid-season just three years later. 1958 Cy Young winner Bob Turley blew up a year later. And countless careers ended as did Mel Stottlemyre’s: with a run in, a man on, and nobody out in the top of the 4th at Shea Stadium on June 11, 1974 (he’d come back for two more innings two months later, then pitch a little the following March, but his rotator cuff was gone).

But the reality is that more pitchers today are warned in advance of these potentially career-ending events. Wainwright isn’t necessarily a victim of some awful turn in pitching mechanics, but rather the beneficiary of greater understanding of their impact, and far greater options in terms of repair. Given how little pain he reported, if this ligament issue had sprung up in Spring Training 1911, he would’ve tried to pitch through the pain, because contrary to today, his livelihood depended on not resting an injury. He might’ve struggled to an 11-12 record this year, had constant pain, started ’12 0-3 and wild as anything, and gone to the minors, never to be heard from again.

Still there is the nagging suspicion that we are doing something to our pitchers that makes Complete Games chimerical dreams, and the four-man rotation and the nine-man staff as comically antiquated as the horse-and-buggy. Denny McLain spent August 29, 1966 – as The Sporting News merrily noted – “struggling to a 6-3 decision over the Orioles…McLain allowed eight hits, walked nine, and struck out 11.” He threw 229 pitches. Two seasons later McLain started 41 games (and won 31 of them). Three years later, he started 41 games (and won 24 of them). The other stat – 51 Complete Games in the two seasons – was not repeated not because of arm problems but due to a suspension for associating with gamblers (the arm problems came a year later).

We know pitchers no longer “save” anything for the 9th Inning (that went out with Jack Morris; it used to be true of the top 25 starters in each league), and that without a fastball in the high 80’s you will now never get signed, and unless something else about you is spectacular, even that will only get you a career serving as the Washington Generals to the Harlem Globetrotter Prospects in the minors.

But I have long wondered if one tiny change of rituals might have contributed just enough to the wear-and-tear on pitchers to have actually made a difference. The ritual is represented by the smiling fellow at the left, Galen Cisco, the long-time pitching coach who hurled for the Red Sox, Mets, and Royals from ’61 through ’69.

But I have long wondered if one tiny change of rituals might have contributed just enough to the wear-and-tear on pitchers to have actually made a difference. The ritual is represented by the smiling fellow at the left, Galen Cisco, the long-time pitching coach who hurled for the Red Sox, Mets, and Royals from ’61 through ’69.

On August 7th, 1964, Al Jackson of the Mets gave up three runs in the first inning. The next day it was two off Cisco; a day later, one off Tracy Stallard in the first. Then came two consecutive scoreless firsts, followed by a doubleheader in which Jackson surrendered one in the first of the opener and Stallard three in the first of the nightcap. Finally on August 15th came the deluge: six first inning runs off Jack Fisher. So as they sent Cisco out to start on August 16, manager Casey Stengel and coach Mel Harder did something radical.

Cisco promptly retired Tony Gonzalez, Dick Allen, and Johnny Callison, and an ecstatic Lindsey Nelson told his Mets radio audience: “Galen Cisco, who warmed up in the bullpen, where there is a mound, in an effort to be better prepared in the top half of the first inning, gets them out in order!”

Your inference is correct. In 1964, starting pitchers did not automatically warm up in the bullpen. When I first heard this old tape I was flashed back to the summer of my tenth year, and the newfound joy of seeing a doubleheader from behind the screen at Yankee Stadium. There, in my mind’s eye, are the starters in the nightcap, Stan Bahnsen of the Yankees and Joe Coleman of the Washington Senators, warming up, on either side of the plate, throwing to catchers whose butts are pressed up against the backstop.

Years ago, Cisco, by then pitching coach of the Phils, insisted to me that he had been no trailblazer, and he had warmed up in the bullpen before August 16, 1964, and that other pitchers had, too. But I know I saw Elrod Hendricks, wearing a mask, warming somebody up long before a game at the new Yankee Stadium, dating it no later than 1976. I was on the field and I had to walk all the way around he and his pitcher. I photographed Goose Gossage throwing, and throwing hard, to somebody in front of the visitors’ dugout in New York that same summer, and it was four years later that I got trapped in a space beyond the third base camera well at Shea Stadium because Scott Sanderson and another Expo twirler were airing it out, pre-game.

Somewhere in the twenty year span of the ’60s and ’70s, the idea that relievers warmed up in the bullpen because they had to “get ready fast,” but starters should warm up from a rubber just on the foul side of either the first or third base foul line, changed into what we see today: everybody warms up in the pen, before, during, or after a game, and again between starts.

Ever had a workout with a trainer? Or just a well-led class at a gym? From yoga to weights, if the guy or gal wants to punish you, they’ll have you do whatever you’re doing, on an uneven surface. Incline or decline, it’s tougher if you’re not on flat ground. To really burn you, they’ll even have you stride downwards or upwards as you lift that weight or try to balance on one foot.

This is not offered as an explanation for all of the woes of the modern pitcher. But a warm-up pitch thrown from a mound is a distant cousin of a pitch to Pujols with two on and nobody out in the 5th. A warm-up pitch from the flat ground is a distant cousin of…playing catch. In short, if Denny McLain had 229 pitches in him on one day in August, 1966, he didn’t use up 20 or 30 or 50 of them before they played the Anthem.

Maybe that’s why Casey Coleman of the Cubs is really one percent likelier to get catastrophically hurt (and 90% likelier to not throw a Complete Game) than his dad Joe did that night in the Bronx (WP: Coleman, 7-7. CG. 11 K, 2 BB, 2 H, Time: 2:37).

Just a thought.

Ask Not For Whom The BP Tolls, It Tolls For Thee (Revised)

The good BP that is – Baseball Prospectus – the annual forecasting bible aptly blurbed on the back page: “If you’re a baseball fan and you don’t know what BP is, you’re working in a mine without one of those helmets with the light on it” (yes, I’m egotistically quoting my egotistical self).

It’s basically 573 pages of the sports almanac Biff Tannen finds in “Back To The Future II” so the material to mine is practically endless, and you will find it as useful on September 30th as you will today. But the aficionado often goes first to find the collapses that time, tide, and the theories of statistical reduction insist will afflict players you are counting on for your team, real-life or fantasy.

It’s basically 573 pages of the sports almanac Biff Tannen finds in “Back To The Future II” so the material to mine is practically endless, and you will find it as useful on September 30th as you will today. But the aficionado often goes first to find the collapses that time, tide, and the theories of statistical reduction insist will afflict players you are counting on for your team, real-life or fantasy.

In short: BP does not like Josh Hamilton’s chances this year. In the list of the biggest falloffs in WARP (“Wins Above Replacement Player” – basically a measurement of how much

better or worse a player is than the absolute average Schmoe you could

stick out there at his position), it sees Hamilton dropping from 6.9 last year to 2.7 this. Mind you, this does not envision Hamilton winding up as a player-coach at Round Rock; 2.7 still makes him the fifth most all-around useful leftfielder in the majors. The computers still suggest he’ll drop from 32-100-.359/.410/.633 to 22-77-.294/.356/.509.

While similar plummets are predicted for Aubrey Huff, Adrian Beltre, Carl Crawford, and Jose Bautista (try 25 homers, because “if teams are smart, it could be May before he sees an inside fastball”), the most intriguing of them belongs to Austin Jackson of Detroit. As BP’s write-up notes, Jackson led all of baseball with a .393 BABIP (Batting Average On Balls In Play – in other words, what you hit when you actually hit it). Jackson struck out 170 times last year and had a mediocre on-base percentage of .344, and unless those numbers alter positively and profoundly, if his “BABIP” just drops back from Ted Williamsy to kinda great, they see his WARP collapsing from 3.6 to 0.2.

The BP formulae always tend to under-promise for pitchers. Dan Haren, Felix Hernandez, and CC Sabathia are the only guys forecast to win as many as 15 games this year, and that’s obviously an absurdly conservative prediction. Nevertheless it is chilling to see the computer spit out the following seasons for some of the game’s “name” twirlers:

Chris Carpenter: 9-5, 94 SO, 3.21 ERA

Phil Hughes: 8-6, 109 SO, 3.74 ERA

Zack Greinke: 11-7, 166 SO, 3.52 ERA

David Price: 12-8, 147 SO, 3.46 ERA

Tim Lincecum: 12-6, 190 SO, 2.74 ERA

It also doesn’t look so hot for some of the game’s closers, listed by predicted saves: Jose Valverde, 20; Carlos Marmol, 17; David Aardsma, 17; Brandon Lyon, 15; Brad Lidge, 15.

Last year’s biggest predicted collapse was Derek Jeter, and in fact the BP boys and girls turned out to have been optimistic. This year, the accompanying biography makes me look like Jeter’s most hopeful fan:

“Jeter pushed for a contract of four years and up, which suggests at least one of the following: (A) while Jeter may be the closest thing the modern Yankees have to Joe DiMaggio, he lacks DiMaggio’s sense of dignity; (B) never mind winning, it’s money that matters; (C) the emperor has no clothes but doesn’t know; (D) the emperor has no clothes but doesn’t care.”

Ouch.

Still, the PECOTA equations don’t see Jeter getting appreciably worse than last year (9-66-.281-.348-.377 compared to 2010’s 10-67-.270/.340/,370) but does see the once mighty warrior’s WARP sinking to 1.0. For contrast, Jeter’s great 2009 season had a WARP of 4.2, the top two shortstop numbers for 2011 belong to Hanley Ramirez at 4.8 and Tulowitzki at 4.7, and J.J. Hardy is a 1.9.

Having pilfered so much of their hard work, I feel it’s imperative to throw out some teasers to get you to buy this essential tome. Granted, at the BP website, the computers refine and refine these numbers even as the season progresses, but right now they somehow see Ryan Rohlinger absolutely tearing up the pea patch for the Giants this year, adore Javy Vazquez in Florida and Lance Berkman in St. Louis, and see potential breakout years for Sam LeCure, Brad Emaus, and Robinson Chirinos that even those players probably don’t.

And I’ll confess right now I had no idea who Robinson Chirinos was. Another reason to secure Baseball Prospectus 2011. However much you think you know about baseball, they know more than you do.

Albert Pujols: Sign The Contract (Updated)

Seriously? Who’s going to taunt him? Joe Mauer? A-Rod?

01 New York 19,171,09102 New York 19,171,09103 Los Angeles 12,981,19904 Los Angeles 12,981,19905 Chicago 9,645,49806 Chicago 9,645,49807 Boston 7,432,65508 Texas (D/FtW) 6,594,14509 Houston 6,008,27310 Philadelphia 5,996,00811 Florida (Miami) 5,592,35012 Washington 5,574,54613 Toronto 5,623,45014 Atlanta 5,564,84015 Arizona (Phx) 4,480,86516 Detroit 4,383,09317 SF-Oakland 4,375,47018 SF-Oakland 4,375,47019 Seattle 3,459,05920 Minnesota 3,302,01621 San Diego 3,088,31222 St.Louis 2,839,29223 Tampa Bay 2,764,53724 Baltimore 2,704,06025 Colorado 2,604,00626 Pittsburgh 2,354,52327 Cincinnati 2,185,14928 Cleveland 2,091,28629 Kansas City 2,067,58530 Milwaukee 1,559,667

False Spring In New York

Pitchers and Catchers report, New York temperatures clear 40 degrees, and somebody issues a forecast that references “55” by the end of the week and it’s not the age of the latest pitcher the Yankees invited to camp.

sses Young and Capuano, and the likelihood that R.A. Dickey actually found himself last season at the age of 35). And the bullpen? You don’t want to know about the bullpen.

Chuck Tanner

I cannot convey to you how frightening it was to be a frequent presence on a major league baseball field at the age of 17. Every player seemed to be about 30 feet tall, and every club official and stadium security officer seemed to be within 30 seconds of chucking me back into the stands, no matter how many credentials I might have had. And the team managers? Ralph Houk? Billy Martin? Earl Weaver?

ing the historical original, in this case the 1962 set: you’ll notice nearly all the Mets and Astros are capless (just as they were in ’62, for far different reasons) and the lettering and the posing is very precise.