Category: Uncategorized

We Shall Not Forget (Provided You Pay)

For four years, MLB has exploited all the in-season holidays – Memorial Day, July 4th, Labor Day – plus on many occasions 9/11, by having all players wear special caps. Today, caps with an American flag patch stitched on the back, to the left of the inviolable MLB logo, were worn by all clubs and all players.

So, in New York, where in 2001 first the Mets and then the Yankees honored the fallen members of – and the heroic and selfless acts of – the New York Police Department, the New York Fire Department, New York EMS, Port Authority Police, New York Sanitation, and several others by wearing their caps during the games of the weeks after the attacks, Major League Baseball denied the Mets the opportunity to wear those caps again, just for tonight’s anniversary game, the only one being played within a thirty minute ride to the World Trade Center.

According to team Player Representative Josh Thole, the Mets players debated violating the dictum and wearing them anyway. Thole told reporters shortly thereafter that the league was adamant and it was a “no-go.” It is meaningful to realize that only three current Mets were even in the majors a decade ago: Miguel Batista, Willie Harris, and Jason Isringhausen. Evidently the Commissioner’s representative reminded them that the punishment – a heavy fine – would be meted out on ownership, not them (and for all we know, a major fine might cause this team to go out of business before noon tomorrow). For his part, David Wright wore a Police cap on the bench, but even he resisted the temptation to wear it on the field and incur the wrath of the Bean Counters in the Commissioner’s Office.

Those bloodless MLB individuals have been down this path before. Ten years ago, Bud Selig’s initially ruled the Mets and Yankees could not wear the caps during games. The Mets ignored the threat, and MLB decided to give them a pass for a game or two, and then the Mets kept wearing them, and MLB wisely backed off their nonsensical decision. Tonight’s ruling reminded everybody that at the moment of the nation’s greatest grief, MLB’s money-making instinct was unhindered by the blood and destruction and fear.

At least in 2001 the sport was smart enough to shut up. Not this year. MLB first blocked the Washington Nationals from wearing military caps in tribute after a disaster in Afghanistan last month. Then came this decision, complete with in the kind of stupidity that would make a megalomaniac proud: they blamed it on MLB Vice President Joe Torre, the native New Yorker who wore these caps at the end of the 2001 season. So if it hadn’t been shameful already, pinning it on Torre made it doubly shameful.

As an aside, I should note that I actually got a tweet from an idiot who wondered why I thought wearing the NYPD/NYFD/PAPD/EMS caps was somehow “patriotic.” It never crossed my mind. It has nothing to do with patriotism. 343 firefighters and paramedics died that day. 23 New York policemen did. And 47 from the Port Authority Police. This is about remembering them – and acknowledging what all those who survived did for this city and the wounds they still have. For me, as the grandson of a New York fireman, and the descendant of several others, and many NYPD and regional PD, this is something deeper than patriotism.

CitiField is, of course, ringed with commemorations and in particular the “We Shall Not Forget” logo placed in the ad right behind the batter’s box. And it has all been rendered utterly hollow because of the crassness of the decision about the NYPD/FD/EMS caps. If you still haven’t figured out why MLB is permitting this public relations disaster to happen; why Commissioner Bud Selig didn’t get on the phone and tell the Mets they could wear those caps right away and damn the consequences, the answer is to be found here.

In case you don’t want to follow the link, here’s your answer: this is available as of tonight directly from MLB for just $36.99.

I guess we should be happy it has an American flag, and that MLB just didn’t sell the space to the highest bidder.

Baseball And 9/11: Continuity, Not Healing

When the anniversary was a week and not a decade, baseball resumed, and as with everything else about the game, it began to cover itself both in glory and shamelessness. Even on this very day MLB is to some degree — apparent or not — selling its role as national healer in the wake of the nightmare here in New York.

It is an exaggeration to say baseball healed the country, or helped heal it – let alone the city. Any true healing has come through love, and friendship, and counseling, and faith, and heroism, and public service. After the World Series ended, the longest winter in the history of New York began, it wasn’t any shorter because games had resumed on September 18, 2001.

I’m being this brutal for a purpose. I have never been comfortable with baseball’s insistence that it provided this role of healing, especially because in fact it provided something more enduring and even useful. This isn’t to single out the sport, or any sport: the then-Commissioner of the NFL Paul Tagliabue insisted he was postponing the games of September 16-17 out of respect for the victims, when he’d been told by the airlines and the FAA on a conference call that the resumption of air traffic would be so chaotic that no power on earth could guarantee him that all his teams could get to all their destinations (or back) on time.

There is no shame in not being “the healer” of 9/11. If you were healed by baseball, a) you probably weren’t in New York, and/or b) you probably weren’t that wounded. I came no closer to personal loss than having two college acquaintances lost in one of the buildings, and a professional friend on each of three of the four airplanes – and my experiences as a radio reporter covering the scene for the first 40 days – and baseball has been part of the fabric of my being since 1967, and I’m not yet “healed” from 9/11. A friend just sent me an mP3 of one of my stories today. It was the first time I had been able to gather the strength to listen to the piece since 2001.

Baseball didn’t “heal” any of us. What it did – far more importantly, I feel – is provide continuity at a time of total derangement from routine. Games outside the city provided Americans elsewhere to hold up “We Are All New Yorkers” signs – a spirit that quickly dissipated but which was of great value in the first week. Players, especially those of the Mets and Yankees, provided extraordinary public service in the days after the attacks and were of unique support to the first responders. It’s almost never stated but there were people who left New York, some forever. Not one of the athletes did – and it is imperative to remember that the assumption here was that we would be attacked again (as we were, though clearly separately, with the anthrax mailings).

There was great courage in this. And the same credit extends to the fans, at a time when public gatherings of 50,000 people in hard to control public venues like Yankee Stadium or Shea Stadium seemed the easiest target for terrorism. We are talking about a time when a smoke bomb causing absolutely no damage could have started a stampede with untold consequences, and yet by the time of an interfaith prayer service at Yankee Stadium on September 23, the Mets and Braves drew a larger crowd at Shea.

As somebody who was at the first game back at Shea, and at all of the World Series games, and who had his press pass grabbed by a police captain who looked at it and me and said a little too excitedly “They could kill him, steal this, and get inside,” I thought that Sunday Mets’ attendance was a wonderful sign. People were picking up their lives and remembering to enjoy themselves again.

What baseball was providing was not healing but sameness. In saluting the victims, baseball and its players were not just reminding us how much had been lost, but also how much, much more remained. Baseball was essential not for magic curing powers, but because it is our primary link to whatever simpler or better or just younger days have gone before, and it can be our connection to those who have passed, and because of the unstated symbolism of our place in the crowd: our place as part of humanity. The crowd, in a way, is mankind.

But ultimately, in simple words requiring very little interpretation, baseball’s role after 9/11 – indeed its role after any tragedy, national or personal – was eloquently expressed on the morning of September 18. I had been downtown at the crack of dawn to cover the eerie reopening of Wall Street, and the juxtaposition of men and women in expensive suits, tracking through streets covered by this awful paste-like coating of debris from the Trade Center and the still-burning pyre, marching like prisoners past police and national guard with machine guns.

It had been a long, long morning and I was preparing to go home for awhile, when I was approached by a policeman who obviously knew me from my ESPN days. “This is something,” he said as we stared at the giant American flag hanging from the Stock Exchange, still occasionally obscured by gusts of smoke coming from the Ground Zero fire. I agreed with him. “But I’ve got one question for you.” I braced myself. “Do you think the Mets can do it? Can they come back and win the Division? They were really getting going till last week.”

I remember freezing for a moment and then giving him some poorly-devised and no doubt self-contradicting answer. Then I asked him how, given all he’d seen, given what he’d be seeing the rest of that day, and all the days and months to come – how it could possibly matter.

“It doesn’t, not really,” he admitted without hesitation. “But I’ll tell you what. All day today, all weekend, I’ve been thinking, ‘At 7 O’Clock on Tuesday night I can put up my feet and watch the Mets in Pittsburgh and pretend for a little while that none of this has happened. So, that way, it does matter.”

And that – not healing – was baseball’s gift and baseball’s role, and what baseball can rightfully claim as the part it played.

Banquo’s Closer

If you can look into the seeds of time,

And say which grain will grow and which will not,

Speak then to me, who neither beg nor fear

Your favors nor your hate.

I’ve always liked that snippet from Banquo’s second speech in Act 1, Scene 3, of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. But as fans have gotten more and more aware of the minor leagues and player development, it’s become more and more applicable to baseball.

“Which grain will grow and which will not…”

Hmmm.

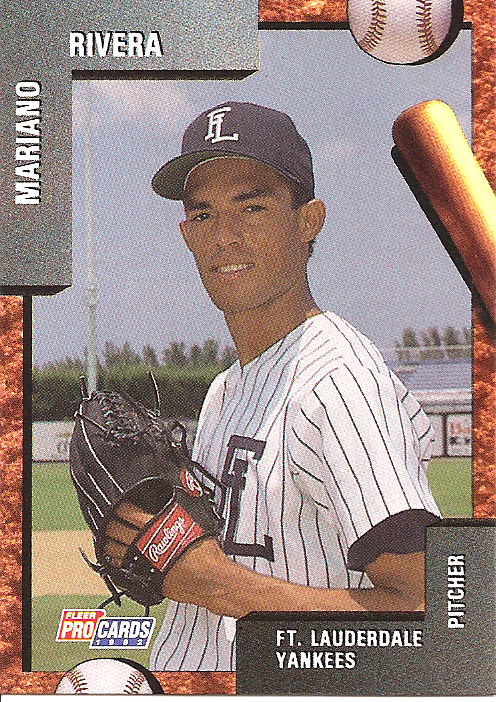

Here are some images from the 1992 Fleer ProCards set of the Fort Lauderdale Yankees of the Florida State League. 20 seasons have come and gone since these kids were the future, and there were more opinions about them than each had seasons under his belt.

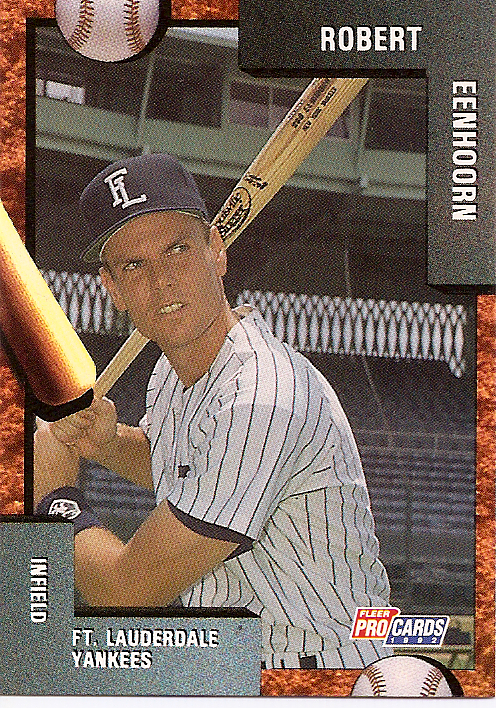

Do you remember this guy? Second-round pick in the 1990 draft, gaunt, rangy at 6’3″, 170, with the exotic birthplace of Rotterdam, Holland. The Yankees’ shortstop of the future (as viewed from 1992)…Robert Eenhoorn? It is literally true that he was a Yankee shortstop of the future. In fact, he was the shortstop on May 28, 1995, as the Yankees beat the A’s 4-1 in Oakland. Eenhoorn went 0-for-4, lowering his season performance to 0-for-7. The next game, in Seattle, the Yankees tried another young shortstop to fill in for the injured Tony Fernandez. Jeter somebody.

It is literally true that he was a Yankee shortstop of the future. In fact, he was the shortstop on May 28, 1995, as the Yankees beat the A’s 4-1 in Oakland. Eenhoorn went 0-for-4, lowering his season performance to 0-for-7. The next game, in Seattle, the Yankees tried another young shortstop to fill in for the injured Tony Fernandez. Jeter somebody.

Remember this next guy?

I was at the Expansion Draft, the November after this card was made. The Yankees had just lost him to Florida, and I stepped into the hotel elevator to find General Manager Stick Michael, who looked like he’d just given blood – or was expecting that George Steinbrenner would make sure it was taken from it. He lasted longer than Eenhoorn (he did 202 homers and was on a World’s Championship team in Chicago) but given the baggage he seemed to proudly carry around (he was just arrested on family violence charges last week) it seems Michael’s anxieties were unfounded.

I was at the Expansion Draft, the November after this card was made. The Yankees had just lost him to Florida, and I stepped into the hotel elevator to find General Manager Stick Michael, who looked like he’d just given blood – or was expecting that George Steinbrenner would make sure it was taken from it. He lasted longer than Eenhoorn (he did 202 homers and was on a World’s Championship team in Chicago) but given the baggage he seemed to proudly carry around (he was just arrested on family violence charges last week) it seems Michael’s anxieties were unfounded.

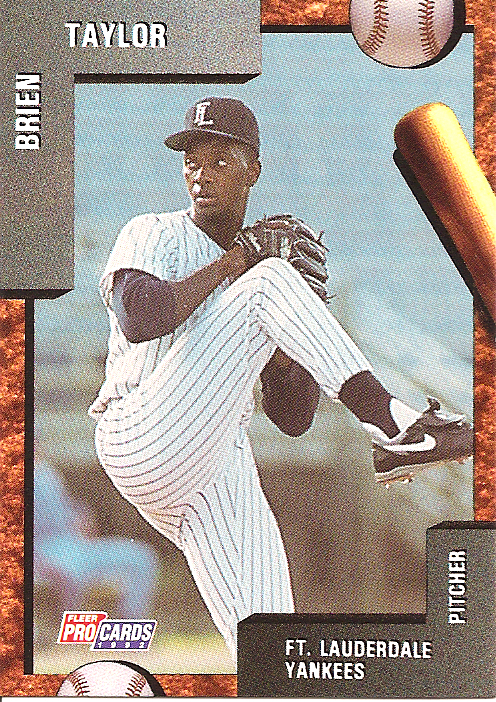

Everett and Eenhoorn were the Yanks’ top two picks in 1990, but this next guy was the star of stars in their system as of 1992 – the first overall pick in the 1991 draft. If you bought this set in 1992, you bought it to get this card:

What is sadder than this?

Brien Taylor was the real deal. I saw him pitch at New Britain, Connecticut. Not only have I never seen anybody throw harder, I’ve never seen anybody throw as effortlessly. His 100-MPH pitches seemed to be thrown about 5% harder than his warm-ups. You couldn’t see any of them from the stands. And then there was a brawl in a bar, and his brother was in trouble, and he went in to help him, and they tore his pitching arm to shreds.

And so the star-crossed 1992 Fort Lauderdale Yankees would mostly be a tale of woe (there’s also a card of Mike Figga – he’d hit a major league home run – and of Domingo Jean – he’d win a major league game). But, if you can look into the seeds of time, and say which grain will grow and which will not, speak to me then.

There was also this skinny pitcher – he made Eenhoorn look robust – who’d struggled in Greensboro the year before (3-4, 5.45, 52 strikeouts to 40 walks) and he’s about to hit a milestone in a career that, frankly, dwarfed everybody else who was playing in the minor leagues when this card was made (and nearly everyone who was playing in the majors).

What Do You Think Of This Guy Scully?

T.J. Simers of The Los Angeles Times has an almost unbelievable column today (and trust me, I’m using “almost” deliberately – some of them are unbelievable), which quotes a Dodgers’ season ticket-holder as saying he’s received a survey from the team asking him (and presumably others like him) to grade the performance of Vin Scully.

While that sinks in, let me regurgitate some basic facts. Vin Scully joined the Dodgers early in the season of 1950. He has been connected with that team so long that two of the eight National League franchises the day he got there, have since moved, and a third has moved twice. Four of the other five have each twice replaced their ballparks. Between expansion and relocation, two-thirds of all the big league clubs are newer at this than Scully is. The late Bob Sheppard, considered an institution at Yankee Stadium since time immemorial, started the year after Scully did, and retired three years ago. He has broadcast Dodger games under twelve U.S. Presidents. Scully has been with the Dodgers for 100% of their seasons in Los Angeles and is generally credited with personally selling the sport and the franchise in its new home. If he isn’t the game’s all-time greatest announcer – if he isn’t sports’ all-time greatest announcer – he’s no worse than second or third.

And the unceasingly tone-deaf Dodgers are asking their fans if he’s any good, in the way that – well, I don’t know, maybe the way ESPN would have asked its viewers after I did the one and only game I ever did (or am ever likely to do) as a major league baseball play-by-play man, in 1993:

On a scale of 1 to 5, “They wanted my opinion of Vin Scully in the following eight areas: 1. Knowledge of baseball; 2. Knowledge of Dodgers organization; 3. Objectivity; 4. Accuracy of calls; 5. Storytelling ability; 6. Focus on the game; 7. Style; 8. Overall performance.”

Simers infers (and I think it’s a reasonable assumption) that somebody in The Fortress Of Solitude On Elysian Park Avenue must be seriously thinking using the poll results against Vinnie. Seems unlikely they’re going to give him an award or a bonus based on whether Steve From Pasadena has given him a 4 or a 5. More likely this is an anti-Scully move in the making, either in an effort to get him to retire, or perhaps in contract negotiations. Either way, it’s madness. Sandy Koufax and Fernando Valenzuela have their enduring legacies but you could add their reps together to those of Don Drysdale and Steve Garvey and pretty much any other fan favorite, and the cumulative weight still wouldn’t reach up to the top of Vin’s ever-polished shoes.

Moreover, if anybody actually attempted to run Vin out of his job before he was ready, the Dodger faithful would rise up with righteous wrath and run the McCourt ownership group out of town faster than you can say “Bankruptcy Referee.”

I am reminded of something that happened years ago. And I put this in this context: I was so nervous about meeting him that I couldn’t screw up the courage to even attempt it until I’d been on television and radio in L.A. for two years. When I finally did, Vin said “I thought maybe you didn’t like me, and it’s funny, because I listen to you every afternoon on KNX. Where on earth do you get those ‘This Day In Baseball History’ facts?” I blurted out my admiration, and my sources, and I’m proud to say he has been dropping these delightful nuggets into his broadcasts for the last 25 years.

Anyway, more recently than that, maybe ten years ago (or about a sixth of his career ago), I found myself in the extraordinary position of sharing one of those priceless “Let’s Complain About Our Bosses” sessions – with Vin Scully! The bosses were two branches of the same octopus (I worked for Fox, and the Dodgers were owned by them) and Vin couldn’t understand why the team suddenly wanted to make changes in his telecasts without consulting him. “I think, just by accident, I probably have a good idea what these viewers want from us, after fifty years. I mean, just humor me and let me go on thinking that!” Why, he wanted to know, did Fox insist on making his game telecast look just like that of the Pirates? “I love Pittsburgh. No offense meant to Pittsburgh. But why should my broadcast look like Pittsburgh’s? Or Pittsburgh’s, like mine?”

The Dodgers defended the poll to Simers by saying they ask their fans about lots of stuff, including all the announcers.

Which brings me back to a version of Scully’s question from 2001:

Why?

When you’ve got Vin Scully, why would you want him to be exactly like anybody else? Why would you even reduce him to being compared to anybody else?

Ubaldo: Have You Got Any More In The Back?

I have told before the story of the argument of the man who built the Yankees’ last twenty years of success, Gene “Stick” Michael, on making a big trade for a star pitcher. Still a consultant when New York was offered Johan Santana for Phil Hughes and Ian Kennedy, Melky Cabrera, and a minor league body, Michael said he would leave the finance and the health to others. But in terms of baseball, he pointed out that whether through injury or under-performance, 50 percent of all pitching prospects don’t even approach their highest ceiling.

Thus, he said, you have to consider the two pitchers as one: Hughnedy, or Kenughes. And suddenly you’re seeing the trade for what it was: one pitcher with 13 so-so major league starts and a proclivity to injury under his belt, for Johan Santana. He said you’d make that deal every day of the week.

And yet the Yankees didn’t make the trade. The money issue is now clear: the only thing the Mets gave up for Santana that has yet to pan out is Philip Humber, and that wasn’t until this year and it wasn’t in Minnesota. The Mets wound up tying up a huge amount of cash in Santana and got one great season, two fair ones, and this one that might see him back from serious surgery to make six or seven starts this year.

Still, the Yankees could’ve afforded that from Santana. As a major league General Manager explained it to me, the reason they didn’t make it was that they must have seen signs that the Twins weren’t certain about Santana’s health. Was he getting extra time between starts? Had his pitch count been limited? Were his innings per-start level, or coming down?

In fact, Santana’s innings per-start had dropped by 0.15% from 2005 to 2006, then another 0.13% from 2006 to 2007, meaning he was coming out of every game roughly one batter sooner in 2007 than he had been in 2005. This other statistic is a little looser as an indicator, but the total number of batters Santana faced in 2007 was 45 fewer than he had in 2006. Doesn’t seem like a lot, but it suggests that the ‘torch factor’ – the exact number of pitches at which you go from being a guy who gets batters out, to a guy who gets torched. For whatever reason, Santana was coming out of games six or seven pitches earlier. That’s a red flag.

All of which brings us to Ubaldo Jimenez. Why wouldn’t you trade for a man who shined the way he did the first half of last year? Why, he was 15-1, and he was still 17-2 and the consensus Cy Young Winner before he got “tired.” He’s a solid citizen, and judging by that ‘bicycle license plate’ commercial, a very funny, grounded man. Heck, he’s got an Emmy Award for narrating a special for the regional cable network in Denver (I don’t have an Emmy Award). Well, in the year since he reached that 15-1 mark, he’s 10-16. And if that number is too obvious for you, let’s go back to the tip-off the Yanks evidently used on Santana. In 2010, Jimenez lasted 6.71 innings per start. This year, he’s lasted 5.86.

That number suggests if he’s not hurt, he’s going to be.

So what did the Indians give up for this? A pitcher in Alex White who had successfully stepped into their rotation before a serious but hardly chronic finger injury knocked him out. He’s just beginning rehab and should be starting for Colorado within a couple of weeks, and he’s a sinkerballer going to the thin air of Denver. Then there’s Joe Gardner, a pitcher who’s struggled in AA, but another sinkerballer. And then there’s Drew Pomeranz, that rarest of pitchers, the lefthanded flamethrower. There’s a high-risk throw-in, an ex-catcher named Matt McBride.

All of this for a Jekyll-and-Hyde starter who is showing early signs that a serious injury is in his immediate future. Or, if it isn’t, that he reached a peak of efficiency last July and has been heading downhill ever since. I’m confident that this is a trade the Indians will regret next year. I think they may regret it next month.

Stuff I Found While Looking For Other Stuff

It never fails. Go looking for anything – from your comb to your Jamie Roseboro 1990 Bowman Glossy Baseball Card, and invariably you’ll stumble across something else. Which explains this card of Robinson Cano’s father, Jose. You may have seen him throwing (and rather successfully) to his son at the Home Run Hitting Contest before the All-Star Game. But the elder Cano actually became associated with the Yankees a quarter century before his son made the team. He signed with them as an 18-year old free agent out of the Dominican in 1980, but lasted just three games with their rookie league team before going home. Little Robby was born two years later, and then Dad returned to this country – and the minors – in ’83 in the Braves system, and made it to the majors in ’89 with the Astros. He pitched only six games, but started three of them, and actually pitched a pretty neat looking seven-hit complete game win over the Reds on the penultimate day of the 1989 season. That would be his last big league appearance, though he did get on two cards in ’90, and this is one of them.

It never fails. Go looking for anything – from your comb to your Jamie Roseboro 1990 Bowman Glossy Baseball Card, and invariably you’ll stumble across something else. Which explains this card of Robinson Cano’s father, Jose. You may have seen him throwing (and rather successfully) to his son at the Home Run Hitting Contest before the All-Star Game. But the elder Cano actually became associated with the Yankees a quarter century before his son made the team. He signed with them as an 18-year old free agent out of the Dominican in 1980, but lasted just three games with their rookie league team before going home. Little Robby was born two years later, and then Dad returned to this country – and the minors – in ’83 in the Braves system, and made it to the majors in ’89 with the Astros. He pitched only six games, but started three of them, and actually pitched a pretty neat looking seven-hit complete game win over the Reds on the penultimate day of the 1989 season. That would be his last big league appearance, though he did get on two cards in ’90, and this is one of them.

The next thing to fall out of the fast pile of stuff that is “the collection” is nothing less than a 1977 TCMA card of a career minor league infielder who would only play 88 games higher than A-ball, and then branch off into another field. Yes, that’s the same Scott Boras, agent to the stars and scourge of general managers and owners everywhere. Boras spent a little more than two seasons with the St. Petersburg Cardinals of the Florida State League, and would actually hit .346 in 22 games during the season in which the card was made before moving up to AA and then winding up in the Cubs’ system. His knees gave up on him, and he went to pursue an alternative career – as a pharmacist. He got that degree and then one in law, and then wound up representing his high school teammate, former big league infielder Mike Fischlin – and the rest was a history of gnashed teeth. Mostly a second baseman and third baseman, Boras actually has some good company in that ’77 set: later Cards’ second base hero Tommy Herr, current Pirates’ pitching coach Ray Searage, and other future major leaguers like Benny Joe Edelen, John Fulgham, John Littlefield, Danny O’Brien, Kelly Paris.

The next thing to fall out of the fast pile of stuff that is “the collection” is nothing less than a 1977 TCMA card of a career minor league infielder who would only play 88 games higher than A-ball, and then branch off into another field. Yes, that’s the same Scott Boras, agent to the stars and scourge of general managers and owners everywhere. Boras spent a little more than two seasons with the St. Petersburg Cardinals of the Florida State League, and would actually hit .346 in 22 games during the season in which the card was made before moving up to AA and then winding up in the Cubs’ system. His knees gave up on him, and he went to pursue an alternative career – as a pharmacist. He got that degree and then one in law, and then wound up representing his high school teammate, former big league infielder Mike Fischlin – and the rest was a history of gnashed teeth. Mostly a second baseman and third baseman, Boras actually has some good company in that ’77 set: later Cards’ second base hero Tommy Herr, current Pirates’ pitching coach Ray Searage, and other future major leaguers like Benny Joe Edelen, John Fulgham, John Littlefield, Danny O’Brien, Kelly Paris.

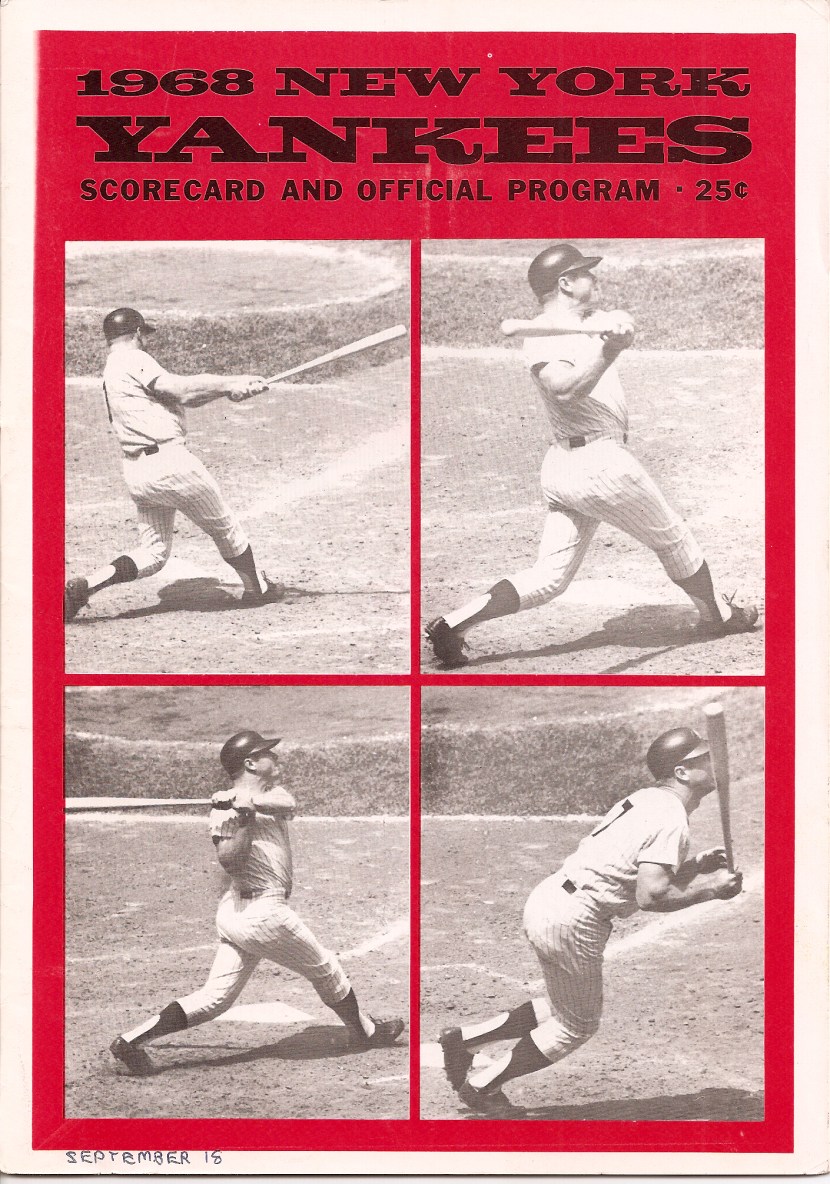

But my favorite rediscovered find is a (slightly) mislabeled 1968 Yankees’ scorecard. The reason I’m showing the cover will be explained below.

The nine-and-a-half-year-old me has marked “September 18” (because that’s the date of the stats inside, as you’ll see below) on the scorecard with the then-state-of-the-art sequence of Mickey Mantle photos. But the game was actually played on the night of September 20, 1968. I remember it vividly, but not for the reason I should. For some reason I can neither recall nor locate, they turned out the lights at Yankee Stadium for the national anthem, and either there was just a light on the singer or band that played it, or people held up lights, or something bizarre. But check out my scorecard – particularly the third inning:

The nine-and-a-half-year-old me has marked “September 18” (because that’s the date of the stats inside, as you’ll see below) on the scorecard with the then-state-of-the-art sequence of Mickey Mantle photos. But the game was actually played on the night of September 20, 1968. I remember it vividly, but not for the reason I should. For some reason I can neither recall nor locate, they turned out the lights at Yankee Stadium for the national anthem, and either there was just a light on the singer or band that played it, or people held up lights, or something bizarre. But check out my scorecard – particularly the third inning:

Yep. In the third inning, against Boston’s Jim Lonborg, Mantle – as the four horizontal lines suggest – homered.

Yep. In the third inning, against Boston’s Jim Lonborg, Mantle – as the four horizontal lines suggest – homered.

It was the 536th – and final – home run of his career.

I saw Mantle’s last homer. But I remember the darkened Stadium much more clearly.

If you’re wondering, this isn’t a bad scorecard for a nine-year old kid. I’ve already got the concept of marking runs batted in (the asterisks) although I was still dabbling with the backwards “K” for a walk. It was popular at the time.

I only became a baseball fan in 1967 so I didn’t get to see very much Mantlean glory. But in addition to the farewell blast (which was also his next-to-last hit; he singled on September 25 versus Cleveland, costing Luis Tiant a no-hitter), earlier in 1968 I saw him hit a homer in the same game as a brash young kid from Oakland hit one. Fella was named Reggie Jackson.

Eduardo Nunez Of The Above

As I watched the replay of Eduardo Nunez’s 127th fielding chance of the season turn into his 11th error of the season (and open up the gates of hell for five unearned Toronto runs in the New York Yankees’ defensive inning of the second half), I was reminded of two virtually identical sentences about Nunez that were spoken, months apart, by two different Major League General Managers.

“As near as I can tell,” the first told me, “there are only two clubs who believe Nunez is anything more than a glorified utility infielder – the Yankees and Seattle.” The other said “I believe only two teams believe Nunez is more than a utilityman – maybe a Wilson Betemit. Seattle and the Yankees. And I’m not sure the Yankees really believe it.”

Both of these GM’s believed, but could not offer evidence about, the story that the Yankees and Mariners had agreed on a deal last summer of Cliff Lee for Jesus Montero and somebody, and then when M’s GM Jack Zduriencik demanded that the somebody be Nunez, Brian Cashman bailed out.

So if you’re Seattle, sometimes your best deals are indeed the ones the other GM isn’t sharp enough to take you up on, and take you to the cleaners with.

Nunez is not a major league infielder. There was a joke going around the Yankees earlier this year that he was on the roster entirely to make Derek Jeter look like a defensive all-star. Now the joke is, the Yankees feel they can trust all those whistling liners towards left that A.J. Burnett and Bartolo Colon and Freddy Garcia and Sergio (“Who Am I? What Am I Doing Here?”) Mitre will surrender in the second half, to Eduardo Nunez and what was his .920 fielding average before #11 dribbled away tonight.

The GM who doubted that the Yankees really thought highly of Nunez said if I could see his scouting reports on Yank prospects and compare them to New York’s own I would assume there were 50 or so Yankee farmhands who had the same names as other, far lesser players. It is not atypical for teams to hype prospects – the trade market is now largely based on prospects – but it is awfully unusual to see a team actually begin to believe its inflated opinion of a minor leaguer.

Nunez already disproved theories that he might be a big league shortstop (91 chances, 9 errors). Now he’s working on third base. They’ve only experimented with him in the outfield and there might yet to be salvation there. He seems to have a viable bat, with a little pop, and a propensity to get very hot for very short periods of time. But if this is all he’s going to be, and they didn’t trade him and Montero for Cliff Lee, the Yankee front office is sillier than it seems even from the outside.

My goodness, as I was finishing this up, he just fumbled another one and just barely got the ball to second for the force (on a high throw). Which makes this headline laugh-out-loud funny.

Why Ryan Vogelsong Isn’t An All-Star

I rocketed past this point in this morning’s post because I thought it was so obvious. But the blowback on Twitter from some Giants fans was as if I had said Tim Lincecum didn’t belong on the NL All-Star team (he probably doesn’t, either, but there’s an argument to be made for previous performance counting).

“What about overcoming the odds?,” I was asked. “Wins are the poorest metric of a pitcher’s performance,” I was told. “Ever read Moneyball, idiot?,” I was hit with (yeah, and Moneyball has yet to produce a league champion, let alone a World Champion). When I argued that Vogelsong shouldn’t have even been considered because he had been tested so much less that he had not yet thrown enough innings to be considered for the ERA leadership, I was told that he would achieve that in his next start. The point was missed: in his “season” he is about where all the other starters were three weeks ago. If he were to give up five runs in five innings in his next start that sparkling ERA to which his supporters point, would balloon to 2.52. Remember that number.

But these guys love them some Ryan Vogelsong.

Trust me, I’ve got nothing against him. Great story, wonderful to see him make his way back (although I don’t recall many Giants fans saying the same thing about Colby Lewis during the World Series last year). He’s pitched well, although you could argue he’s been no better than the 14th or 15th top starter in the National League this season.

Actually, the explanation for the heading “Why Ryan Vogelsong Isn’t An All-Star” takes just two words: Tommy Hanson. Opponents are hitting .222 off Vogelsong. They are hitting .192 off Hanson. Vogelsong has averaged 7.26 strikeouts per nine innings. Hanson has averaged 9.62 of them. Vogelsong’s WHIP is 1.15. Hanson’s is 1.04. Vogelsong has won 6 of 13 starts. Hanson has won 10 of 16. In one category and one category alone does Vogelsong best the Braves’ righthander. His ERA is 2.13 and Hanson’s is 2.52 – exactly where Vogelsong could wind up with a five earnies in five innings performance next time out.

I think it’s open and shut right there. Individual metrics are all in Hanson’s favor, and the results – and some day we will shake off the Felix Hernandez foolishness of last year and recognize that, yes, a win or a loss is at least somewhat a starting pitcher’s responsibility – the results are decidedly in Hanson’s favor.

His interiors aren’t that impressive, but the idea that Kevin Correia has won 11 games with what is still a dicey Pirates’ line-up, is extraordinary. A 3.74 ERA and a .260 opponents’ BA give me the willies. But wins and losses do count for something.

But there are several other pitchers – and for our purposes here these are pitchers drawn only from the same Cinderella category to which Vogelsong belongs – whose statistics and results are slightly better or just slightly worse than Vogelsong’s. It’s easiest to look at them in column form:

PITCHER W-L ERA WHIP OBA SO/9

Ryan Vogelsong 6-1 2.13 1.15 .222 7.26

Dillon Gee 8-3 3.47 1.20 .222 6.29

Jeff Karstens 7-4 2.55 1.07 .240 5.29

Ian Kennedy 8-3 3.38 1.14 .236 7.58

Shawn Marcum 7-3 3.32 1.15 .221 8.26

Jordan Zimmermann 5-7 2.82 1.10 .240 6.29

The crazy thing here, of course, is that our hypothetical five innings, five earned start for Vogelsong not only gives Hanson a shutout on the stat board, but it also turns the Giant into only a slightly shinier version of Jeff Karstens.

But I have heretofore left out the favorite meme of the Vogelsongians: he pitches for the Giants therefore he must be better because the Giants never score runs and every game is torture and blah blah blah, blah blah.

Sorry.

Correia and Gee, you can dismiss on this point. The Buccos are scoring Correia 7.17 runs per game; the Mets 6.94 for Gee. But all the other pitchers mentioned here are getting, at most, half a run more per outing than is Vogelsong, who gets 5.44 (Marcum 5.96, Kennedy 5.81, Hanson 5.70, Karstens 5.56 – and poor Jordan Zimmermann is struggling along at 4.80). If you want a macro view of where a 5.44 run support should get you, Cole Hamels was getting a 5.37 and Jair Jurrjens a 4.88 before their starts tonight. And somehow in the American League, Michael Pineda is doing what he’s doing with an RS of 4.42, Jered Weaver’s getting 4.04, and poor Dan Haren, 3.87. That’s lack of support.

This is a good point to mention my all-time favorite season of any pitcher in professional history. It’s amazingly instructive about the true value of interior statistics. At first blush, this looks like a pretty good year, in AA ball, for a 22-year old pitcher in 1967: 2.81 ERA (that’s two earned runs in each of his 20 starts, 1.39 WHIP (he was a little wild), 5.3 K/9, only 7 homers allowed all year. His name was Dick Such, his team was the 1967 York White Roses, they were no-hit four times that year, and Such finished the season 0-16. That’s right: no wins, 16 losses. Rather remarkably, he not only didn’t quit the sport, but made it to the majors as a pitcher and, for 19 years as a pitching coach (16-1/2 with the Twins).

There’s one more deeply disturbing aspect to Vogelsong’s selection by his manager Bruce Bochy that was explained on MLB Tonight by Jerry Manuel. To paraphrase him, he said he’d love to be getting the criticism Bochy is getting for picking three of his own starting pitchers, because it meant – no duh – that he had won the pennant last year instead of getting fired.

But more importantly, Manuel observed, it would mean that he had done right by “his guys” – that given the choice between a completely neutral decision about the eight best starters in the league this season, and not offending his own starters, he’d take not offending his own starters, every time.

Jerry’s never been given credit either for his acumen or his honesty. But his point is honest, and damning, and explains why now the time has come to take the defending pennant-winning manager (and all the managers) out of a decisive role in selecting All-Stars. If it has devolved into a popularity contest – as in, I want to stay popular with my own players – then it must be discontinued immediately. And the selection of Vogelsong over Hanson (to say nothing of the other Cinderellas) suggests it has.

Dee Is For Dodgers And Other Notes

The Dodgers have enough to worry about, but the construction in which Rafael Furcal is healthy, Dee Gordon has the makings of a lighter-hitting Jose Reyes, and Jamey Carroll actually has trade value – and they send Gordon back to Albuquerque – is nuts…you trade Carroll before he turns back into a pumpkin, shift the willing Furcal to second and thus reduce some of the wear and tear on his body, and let Gordon run wild and free at the major league level. Anything else suggests the Dodgers are operating under a delusion bigger than any of Frank McCourt’s – that the team is competitive this year….

A lot of leeway has to be given to All-Star managers about selecting pitching staffs, especially members from their own team, but the only man I’ve ever met with a bigger head than my own, Bruce Bochy, swung and missed, twice. One could stretch a point and say Tim Lincecum deserved a trip to Phoenix based on his Cy Young yields and post-season work last year and goofy popularity, but it’s still stretching a point. But Ryan Vogelsong? Helluva story, but not an All-Star. Not even close. Desperate homerism, pathetic, embarrassing. He was an All-Star, and you guys sent him back to AAA in the spring?

Just amazing to see that my Derek Jeter Injury Conspiracy Theory has played out almost exactly as I had written it. As I compose this we are still a few hours away from seeing the line-ups for the last game of the Yankees’ series in Cleveland, but Joe Girardi had already set up Part 2 of the theory by saying Jeter might not play all the games against the Indians. The true test of the theory is if Jeter does not cross the 3,000 hit plateau at home against Tampa Bay, and suddenly has a relapse that takes him out of the team’s subsequent road trip after the All-Star Break.

It may be academic since they may not have any more save situations this year, but if Mark Melancon keeps giving up runs in carload lots, the next youngster to get an audition as Astros’ closer could easily be young David Carpenter. He’s the ex-catcher they got last year from St. Louis for Pedro Feliz. His scoreless streak and minor league domination is obviated a little bit by the fact that he did it in A-ball at ages 24 and 25, but there is some leeway given to the fact that he only moved to the mound full-time in 2009. His demeanor and the strength of his fastball and top breaking pitch seem to make him an ideal candidate, or, at minimum, a suitable set-up man.

I Guess I’m A Former Old Timer (Updated)

This is an all-time first:

I am turning to the sports pages of The New York Post to discover something about my own baseball-related career:

For the last several years, political commentator Keith Olbermann has served as an in-stadium play-by-play man for the Yankees’ Old-Timers’ Day. But the Yankees are making a change, The Post has learned.

The Yankees were not happy with Olbermann posting a photo on Twitter earlier this season of a coach signaling pitches to their batters in the on-deck circle. So they decided to bounce the liberal loudmouth and will have Bob Wolff and Suzyn Waldman provide the commentary for today’s game instead.

Look, it’s their Popsicle Stand and they can do what they want. More over, the Yankees – to use the Post’s phrase – once “bounced” Babe Ruth, to say nothing of Bernie Williams, and Yogi Berra twice and Billy Martin five times. I’m making no comparison, of course. But in that context, I’ve got no complaint there. I wasn’t going to say anything about this, in fact.

And then somebody from the Yankees leaked it to the paper.

On a personal level, however, I do know that I have a legitimate complaint in one respect. Old Timers’ Day is today, and I’ve been doing the “color” on the public address system for the last ten years, and one year prior to that as well (not the play-by-play; that is, obviously, entirely the province of Hall of Famer Bob Wolff and it’s my honor to sit next to him; Suzyn Waldman has usually been with us to do Old Timers’ interviews during the game). After eleven years of doing this, I think it would’ve been fitting if the Yankees had told me rather than let me hear it from somebody outside their organization the week before the event. It just seems like you’d want to preserve the dissemination of details about your company’s decisions like that to your company, rather than have a guy hear a rumor and then have to call up and ask.

I can’t vouch for the legitimacy of the motive described in The Post because this is the first time I’m hearing about it. But on a macro level, that does worry me in terms of the suppression of information. I might have been sitting in the stands when I tweeted the photos in question, but I saw nothing that any eagle-eyed guy in the press box couldn’t have seen (and trust me, they started looking). There was a coaches’ assistant in a Yankee jacket and a Shamwow-Seller’s Headset with a radar gun sitting three rows back of home plate signalling pitch speeds to Alex Rodriguez and other Yankee players in the on-deck circle on Opening Day this year, and I took a picture of it, largely because to see the signals, Rodriguez had to basically look right over my head.

The Yankees explained that the radar gun they used for their scoreboard wasn’t working that day, and the coaches’ assistant, Brett Weber, was simply supplying information the players usually got from the scoreboard. It was technically a violation of a rule prohibiting the transfer of such information from the stands or press box to the field. My point in tweeting the photo was that it didn’t seem to me to be cheating (after all, it was information about the last pitch, not the next one) — it just seemed weird. And after asking that Weber be vacated from his seat for one day, MLB accepted that explanation and he was back the next game – on the proviso that he not do any more signaling. And I haven’t seen him do any more signaling.

The problem, of course, is that Weber signaled all last year, too, and not just pitch speeds. He had a clipboard and some thin cardboard with which he seemed to be explaining to players in the on deck circle what kind of pitch they had just seen, and where it was. After the storm about the tweet broke, I talked to several friends of mine who happen to be American League managers. One real veteran gave me particular kidding grief about it and when I said it wasn’t anything new and had started the year before, he said “The hell it did. They’ve been doing all the years I’ve been coming to this place and the old Stadium and we complain and complain and nobody’s ever done anything about it before.”

For generations – and I mean pretty much since Jacob Ruppert bought the team in 1915 (or maybe it was from the time it moved from Baltimore in 1903), the Yankees have been notorious for trying to manage information. I can remember the day in a playoff series when they went after a fly with a cannon. We were setting up the interview stand in the clubhouse as the Yankees moved to within a few outs of eliminating advancing. Suddenly, the door opened and as intense a series of obscenities as I’d ever heard resonated through the room. It was a player who was not happy about having just been removed from the decisive game before its conclusion. Obviously, we in the Fox crew were being given a great courtesy – a few extra minutes to make our “set” look good. None of us would have dreamed of reporting what the player did – the definition of a gamer who had every right to blow off steam – or to whom his invective was directed. We were reporters, and we were “there” – but we were there under controlled and agreed-to conditions. The threats started to pour out of every Yankee exec who had contact with any of us that if we reported a word of it, there’d be hell to pay and jobs and contracts threatened. And we were all dumbfounded by the overreaction. We got it – and still the Yankees yelled and threatened.

There were far more dire consequences threatened about a story about Roger Clemens nearly getting into a fist-fight with a fan during the subsequent World Series. I had obtained a videotape of the confrontation, but had already decided not to run it, because it showed only Clemens’ response, not the utter and unjustifiable provocation by the fan. It would’ve made a great front page for The Post, but the video not only told just half the story, in doing so, it completely erased the truth of the story and replaced it with images that implied Clemens was entirely at fault. As I say, I had already decided not to run it, told the Yankees I had it, and that I would have to run it if the story got out some other way. And while at least one executive understood my dilemma and thanked me completely for my journalistic restraint, others made efforts to somehow seize the tape from me, or prevent my network from running it (even though we weren’t going to).

I should also point out here that of all the story-suppression efforts, I never got any of them from George Steinbrenner himself. Not even when the story was about how a couple of other reporters seemed to be very close to confirming some very ugly rumors about the owner himself. I contacted the club, mostly to find out if the stuff was true (and potentially to break it myself), and while some of his underlings freaked out, Steinbrenner himself told me he had no complaints. “That’s your job. I get it.”

It’s also kind of a shame that whoever from the Yankees leaked this information about Old Timers Day to The Post put Yankees’ Vice President/General Manager Brian Cashman on the spot. In my previous capacities at SportsCenter, and later as the host of the Playoffs and All-Star Game on NBC, and of Game Of The Week and the World Series on Fox, I have often reported things Cash didn’t like, but he’s always been professional and pleasant and there are few in the media who have had the slightest serious problem with him (a record that very few other Yankee figures of the last 40 years can claim).

The day that The New York Daily News published the story of the tweetpic of Weber, four fingers raised, I happened to be at the ballpark and got corralled by the beat writers who were trying to figure out what it was all about. In the middle of this, Cashman came over to explain, and to say it was no big deal from the Yankees’ point of view (as I said it wasn’t from mine) and to very publicly reassure me that the team had no problem with what I did, or with me.

Today, this statement seems to be inoperative.

Back on that brilliant spring Saturday in April, Cash even had a joking explanation for this: “He was just ordering four beers, Keith,” Cashman said with a laugh.

“He was just ordering four beers, Keith,” Cashman said with a laugh.

So I showed him the picture I didn’t tweet and asked him (with my own laugh), if that was the case, if they really didn’t have a bigger problem than just improper hand-signaling: POSTSCRIPT: You will find this silliness in the comments. It’s worth it

POSTSCRIPT: You will find this silliness in the comments. It’s worth it

I believe this also stems from Keith Tweeting a picture of Jorge Posada’s name crossed out on Joe Girardi’s lineup card on the day Posada asked out of a game. As he was NOT a ‘reporter’ that day, in my opinion, Keith had no right to post that picture other than to fuel his own ego to simply prove he can. Also, KO was obviously trying to embarrass the longtime Yankee catcher who was probably at the all-time low of a generally nice career. Who kicks a guy like that when he’s down? As a baseball fan, I find that itself is unforgivable.

FYI, I’m not only a 20+ year Olbermann fan, but a frequent and loquacious defender of his and the Posada incident has soured me so much I’m sad to say I’m starting to lose faith in his political message around which I have long based my own beliefs.

While the truth may never come out, don’t discount the Posada incident as a reason for Keith’s exclusion from this prestigious Yankee event.

Go Yanks!

Yeah, this is pretty dumb. The tweeted picture this poster has gone nuclear over was of a copy of the printed line-up/scorecard sheets the Yankees give out in the press box and to every spectator in the suites areas who asks for it. It showed where I had crossed off Posada’s name on my sheet and written in Andruw Jones’ name. It was obviously my handwriting. And I tweeted it only to illustrate tangible proof that even the Yankees had been crossed up by Posada’s unwillingness to bat ninth.

Where on earth would I get a copy of Joe Girardi’s line-up card, during a game?